The exhibition was almost ready when the order to cancel came from above.

Set to take place on central Moscow’s trendy Chistoprudny bulvar, the open-air exhibition, part of an ambitious program of celebrations for the centenary of the birth of Andrei Sakharov, was to commemorate the nuclear physicist and Soviet dissident’s campaigns for human rights and world peace.

But on 30 April, only weeks before the displays were due to go up, a terse phone call from the Moscow city government changed everything. The authorities would not approve the content of the exhibits. The exhibition was off.

“I don’t think the order to cancel came from the top,” said Sergei Lukashevich, director of the Sakharov Center, which had organized the exhibit. “This was lower-ranking officials trying to cover themselves.”

“No one really knows what they are allowed to say today, or what they might be allowed to say tomorrow.”

As Russia prepares to mark the 30th anniversary of the end of the U.S.S.R. this year, Sakharov himself remains officially venerated for his role in developing the Soviet nuclear bomb, even while the democratic ideals he championed are increasingly suppressed by a Kremlin that sees the dissolution of the Soviet Union as a traumatic defeat for Russian national interests.

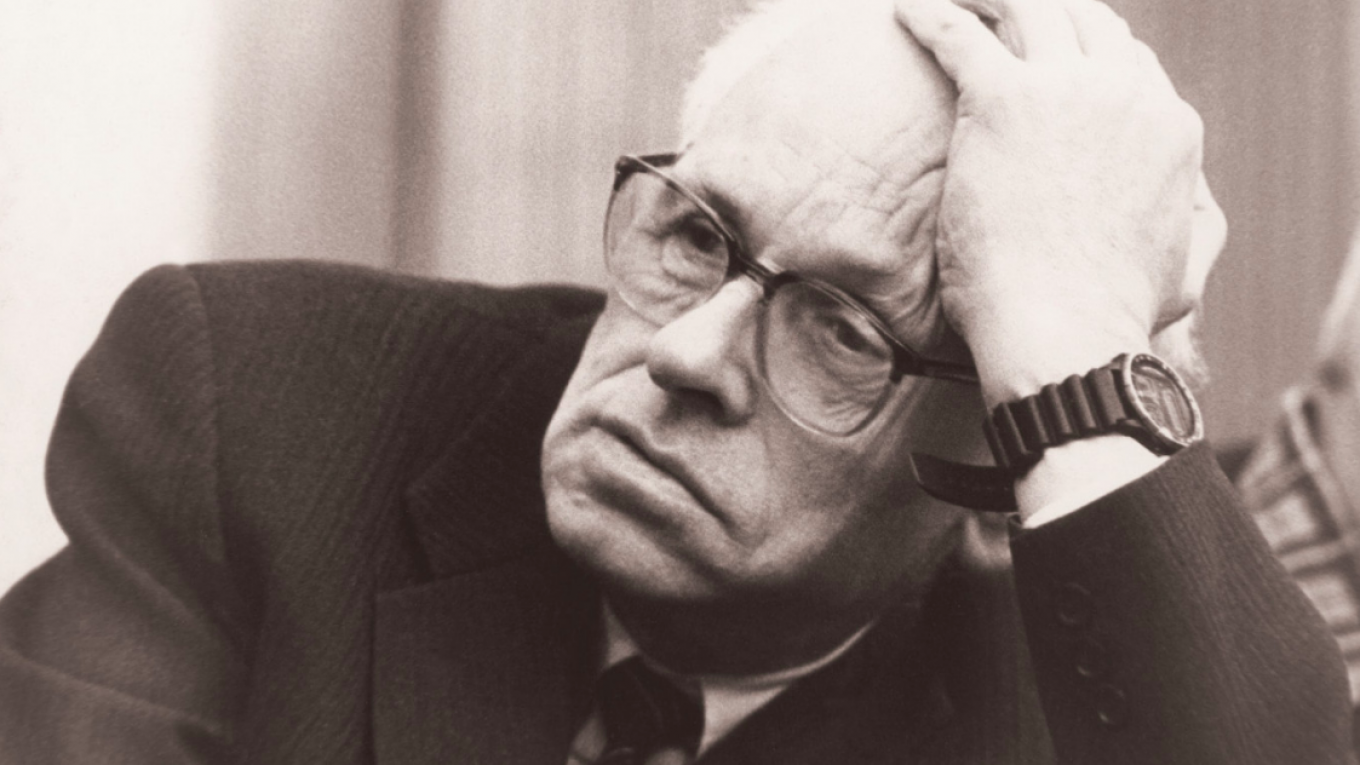

Born the son of a Moscow schoolteacher in 1921 and identified at a young age as a gifted mathematician, the young Sakharov studied for a doctorate in physics before being recruited to join Stalin’s project to build a Soviet atomic bomb in the late 1940s.

Sakharov’s decisive role in developing the Soviet Union’s first hydrogen bomb in 1955, before going on to design the 1961 Tsar Bomb — still the most powerful nuclear weapon ever tested — secured his reputation at home.

Even today, President Vladimir Putin’s official statement on Sakharov’s 100th birthday concentrated on the physicist’s work on the Soviet bomb, largely glossing over his political positions.

“The official position on Sakharov is quite mixed,” said Nikolai Petrov, senior research fellow at Chatham House.

“On the one hand, he is the father of the hydrogen bomb who contributed a great deal to Soviet might. On the other, they see him as someone who went crazy later in life.”

For Sakharov, his role as a pioneer of weapons of mass destruction precipitated a dramatic political turn, as he began to feel profound personal guilt for introducing thermonuclear weapons to the world.

That guilt led Sakharov to radical conclusions. From the late 1960s, Sakharov, once feted as a hero of the Soviet defence industry, became one of the U.S.S.R.’s most prominent dissidents, alongside writer Alexander Solzhenitsyn.

By the early 1970s, he was likening the Soviet Union to “a cancerous cell” that threatened world peace and openly rejecting Marxist-Leninist visions of class conflict, insisting instead on universal human rights in the western mold.

In 1975 he was given the Nobel Peace Prize for his work against the nuclear arms race he had helped precipitate, though he was not permitted to leave the Soviet Union to accept the award.

For Maria Lipman, a Moscow-based political scientist who covered Sakharov’s human rights work as a journalist, the father of the Soviet bomb’s black-and-white moral convictions — under which the West was identified with good, and the Soviet-led bloc with evil — were unusually utopian, even among Soviet dissidents.

“Sakharov was a secular saint, in both good and bad senses,” said Lipman.

“He lived in a world without moral trade-offs, in which absolute good would eventually triumph over absolute evil.”

Arrested in 1980 after denouncing the Soviet war in Afghanistan, Sakharov was sent into internal exile in the city of Nizhny Novgorod, then closed to foreigners.

After six years in exile, during which time he undertook several hunger strikes, Sakharov was released over a telephone call by reformist Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

Back in the Soviet capital at the height of Gorbachev’s rapid-fire reform of the Soviet Union, Sakharov threw himself into activism, demanding faster and more radical changes to the system.

Elected to the Congress of Peoples’ Deputies in the Soviet Union’s first democratic elections, Sakharov became one of the most distinctive personalities of the perestroika era, rising to the status of a national moral authority, above the political fray.

His sudden death in December 1989 only reinforced his iconic status among Russia’s liberals and democrats, with his funeral attended by thousands and transformed into an impromptu political rally.

“We’ve not had anyone comparable to him since,” said Chatham House’s Petrov.

“After he died, no one could play the same role.”

But today, “Sakharov’s legacy is respected only to the point of not saying nasty things about him,” according to Maria Lipman.

Putin has famously described the collapse of the Soviet Union as a “catastrophe,” an opinion shared by almost half of Russians, according to a 2020 poll by the independent Levada Center pollster.

“Dissidents never enjoyed broad public support in the U.S.S.R., unlike in other countries,” said Lipman.

However, Sakharov remains, even so, the object of official veneration, if primarily for the work on the nuclear weapons he later came to disown.

A central Moscow street — the traditional site of opposition protests sanctioned by the city authorities — continues to bear Sakharov’s name, while state TV broadcast a favorable biographical documentary in honor of his 100th birthday.

“If good things are said, they’re likely to be about the bomb, rather than about making Russia free,” said Lipman.

At the same time, however, efforts to highlight Sakharov’s beliefs have come under suspicion, as the Kremlin has rehabilitated elements of the Soviet regime he opposed.

In 2014, the Sakharov Center — a human rights foundation founded by Sakharov’s widow, which has taken anti-Kremlin stances on issues including the Pussy Riot case and the murder of Boris Nemtsov — was recognized as a “foreign agent,” a designation which imposes strict limits on its activities.

For Sergei Lukashevich, director of the Sakharov Center, state hostility to Sakharov’s legacy — including the ban on the planned centenary exhibition — is to be expected.

“In today’s Russia, a lot of what Sakharov said is automatically suspect,” he said.

“Sakharov is crucial to the rhetoric of military greatness, but naturally they don’t want us talking in public about what he actually believed.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.