Even if you don’t know the name, you know who Victoria Ivleva is. She is the only photographer to go inside the destroyed reactor at Chernobyl and the winner of the World Press Photo Golden Eye award for those haunting images.

Ivleva is matter of fact about her feat of courage in the destroyed nuclear plant. “I met the physicists and got friendly with them,” she said, “and I asked them to take me inside. I never thought those shots were great… but later I began to think there was something in them — a little person and that vast, terrible space…”

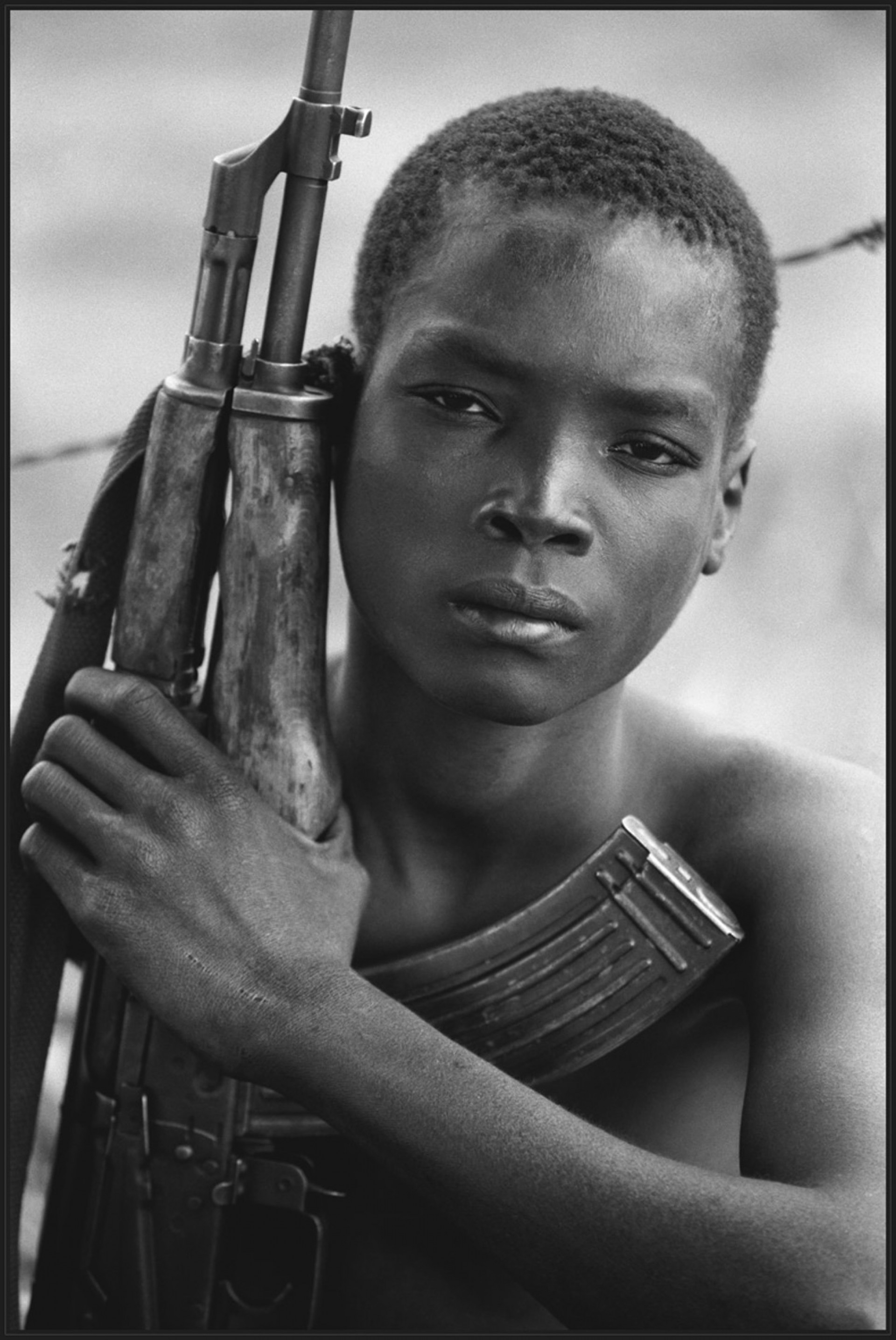

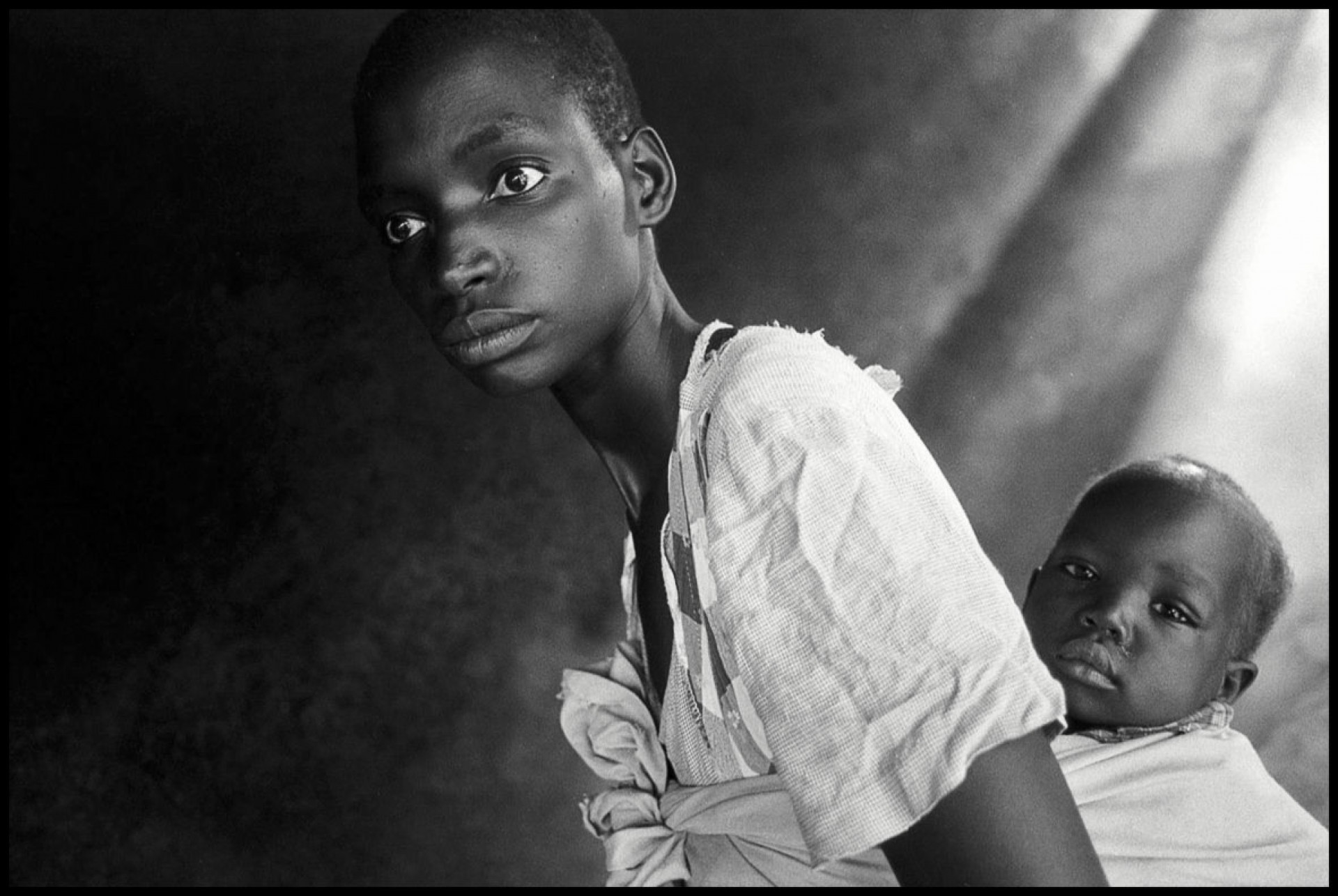

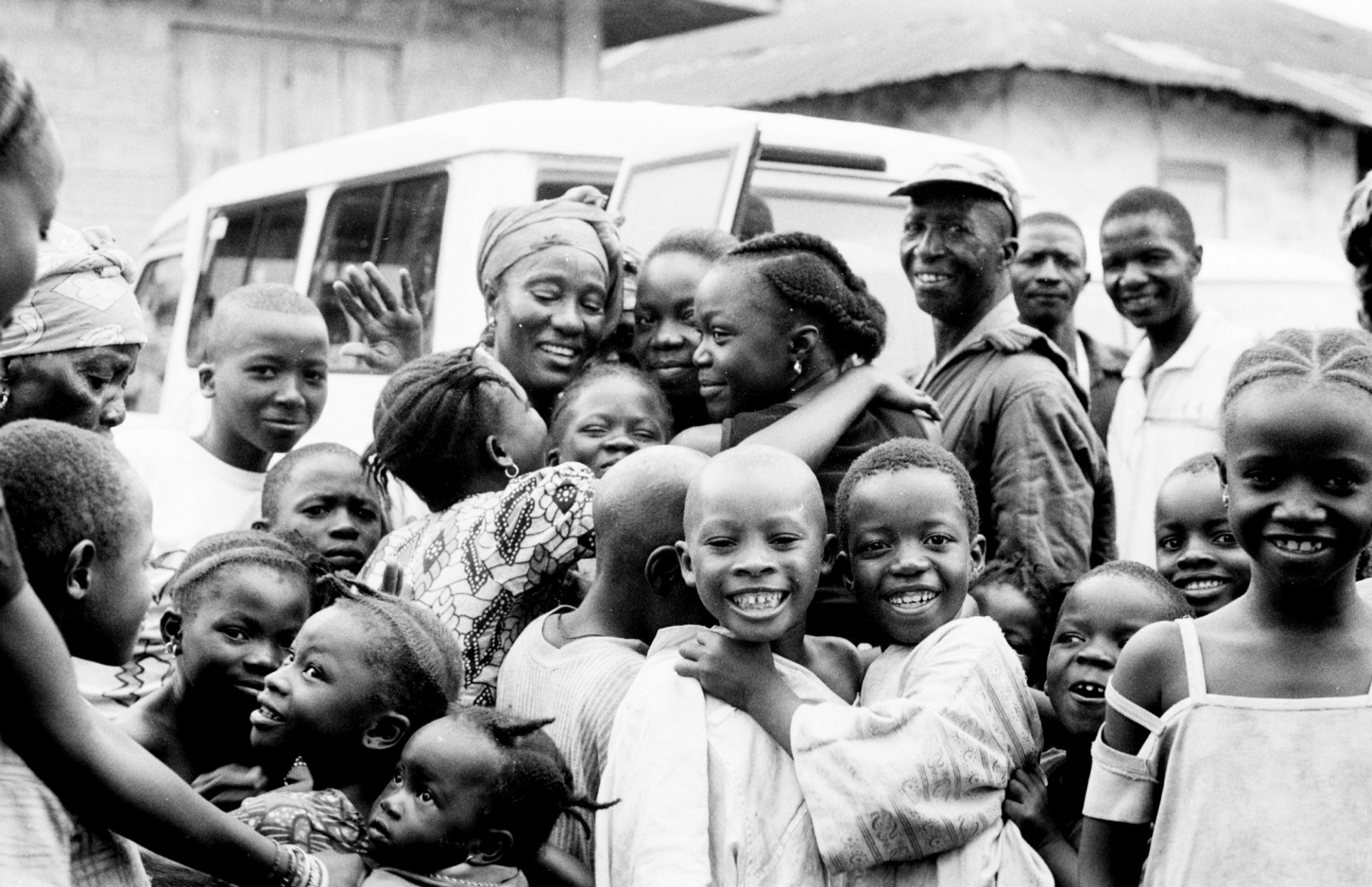

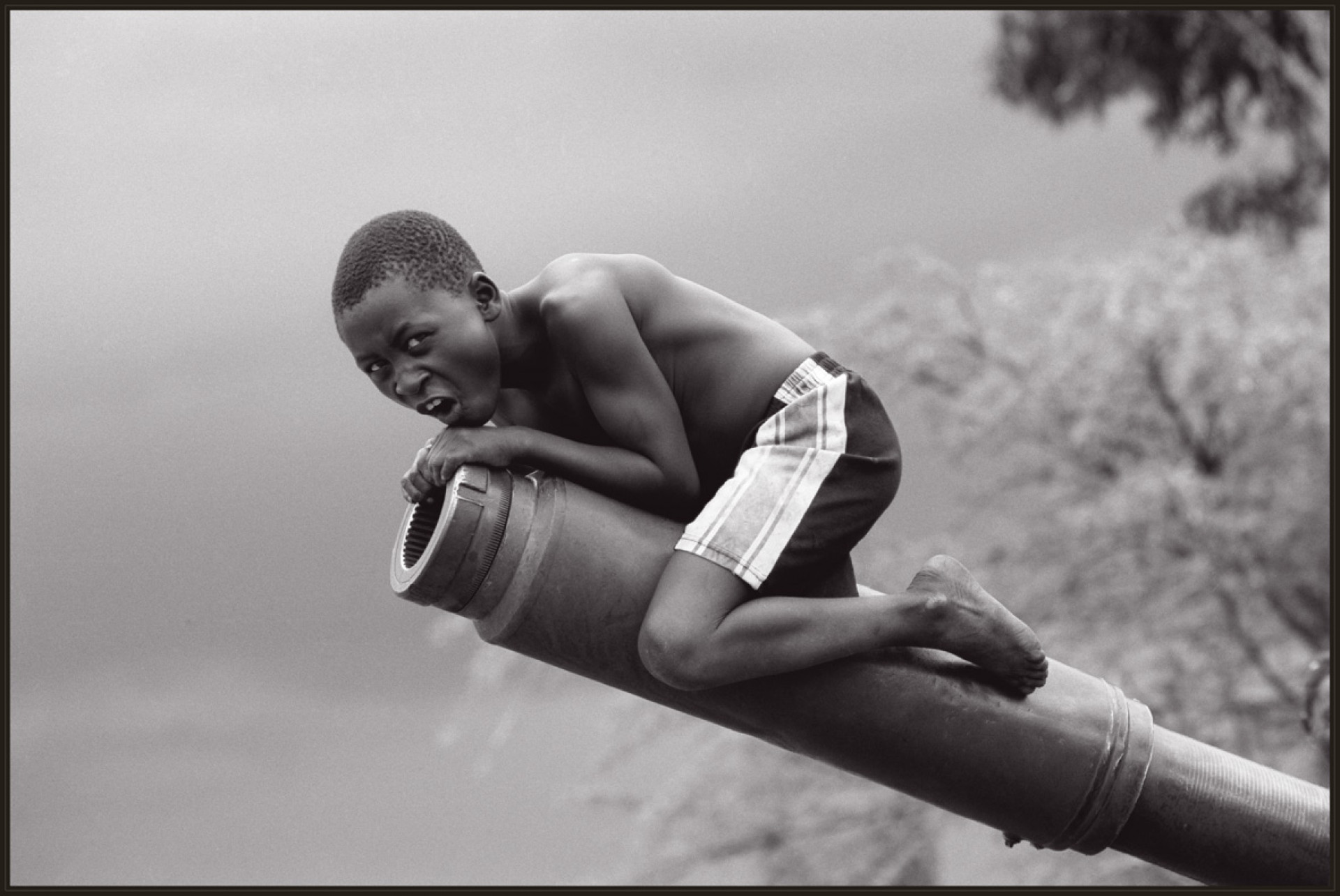

Ivleva has spent her life going to dangerous places, taking photographs, reporting on what she saw, and working as a volunteer and activist, both in Russia and abroad. For the past several weeks, the Voznesensky Center has been hosting an exhibition of her photographs called “African Diaries.” The first event in the Center’s project called "About Africa…" and a continuation of a larger program called "Connecting Cultures," the show is the largest exhibition of photographs from Africa ever to be held in Moscow.

The Moscow Times spoke with Victoria Ivleva about the show, her trips to Africa, her activism and volunteer work. The interview has been edited for length and clarity.

Why did you go to Africa the first time?

In the summer of 1994, I was at the dacha with my 10-month-old baby boy, and I heard that the government was sending humanitarian aid to Rwanda and then taking Russian wives of Rwandans back on the plane. Now that seems normal, but at the time it was something extraordinary. First, because Russian had no interests there… and then because they would be taking home women who had married Rwandans… it was the early Yeltsin period when it was normal for a country to go save its citizens and be ready to help other people who were suffering. I was so happy that Russia was changing.

I called the Ministry Emergency Situations and asked how I could get there. They said that the minister told them not to take women because it was too dangerous… I found someone who knew the minister, Sergei Shoigu…and after I called again and used his name, they called me from the ministry to come in. I met with Shoigu, and after some small talk I told him that I wanted to go to Rwanda. He pushed a button and said, “There’s a woman here who wants to go to Rwanda.” And that was it.

How many trips to you make to Africa? What drew you?

I went five or six times. I’m drawn by human lives and the extreme situations that humans find themselves in. I was also drawn by a sense of guilt, although Russia did less harm there than other countries. Drawn by curiosity. I’m very curious. After talent, which you need in journalism like in all professions, next is curiosity. For journalists, it’s a very important quality. I’m not indifferent.

I believe that we have to pay for everything in this life… The BLM response is not always appropriate, but when you think of what we white people have done to blacks, their response is nothing. In Rwanda, the borders are the cause of all the wars and genocide — Africa is the only continent with straight-line borders, drawn by the colonial powers.

What has the response been to your show?

I’ve been accused of celebrating violence…but I don’t. I have the right to see Africa the way I do. I know there are skyscrapers in Africa, like there are skyscrapers here. But Russia isn’t a country of skyscrapers, it’s a country of great injustices and cruelty right now.

I wanted to call the show “Total Africa,” the essence of Africa, how they live — like people nowhere else in the world, not like people in the U.S. or the poorest places in Asia.

Only when I was preparing the show did I realize that everyone in all the photographs is wearing our cast-off rags. Not clothing that is out of date! They are wearing rags, and we’re so proud of ourselves for sending them those rags.

Tell me a bit about how you work. Why do you prefer to shoot in black and white?

That’s a question of taste more than anything, but today when you can shoot in color and turn it to black and white, you see how much harder it is to shoot in color. Now I shoot on film. I shot a lot on digital, but now on film… when you put the film in, you have 36 frames, a sense of an end point, and your concentration is greater. It’s harder to work. You aren’t thinking: “I’ll fix it later.”

Photo-journalism means shooting the here and now, and you can’t fix the image later. I’m old school: as a journalist, you shoot life and that’s what you get. If you didn’t get the shot, it’s because you did a bad job, so go and learn some more, and then come back and shoot again tomorrow – with no cuts, not putting it together. Out of the 150 photographs in the show, I think I cropped only three. Technology is easier now… but are there more brilliant photographers? In the end, talent is in first place, not technology.

Do you consider yourself an activist as much as a journalist?

In Rwanda I was a volunteer… we picked up people and brought them to the hospital… I never regretted it for a moment… A good photograph is nothing in comparison with saving a person’s life…. Staying detached is fine when everything is fine, when the nursery school is built and there is a theater. But when things start to happen, you aren’t a robot… being detached isn’t always being objective, and being involved doesn’t always mean that you are unobjective.

I am an activist, not an activist-journalist, but an activist as a person. I picketed on Pushkin Square to release Oleg Sentsov [the Ukrainian filmmaker jailed in Crimea-ed.]. I stood for a year outside the presidential administration buildings asking for an exchange of prisoners. And when the Ukrainian sailors were arrested, for the nine months that they were in Lefortovo, we fed them. Twice a month we brought 15 kilos of food to each of them. Twice a month we wrapped up 300 kilos of food for them in my apartment…

Ukraine is my deepest pain. To fight a war with a close neighbor and close friend is a tragedy. If we had a normal government, the first thing we’d do would be to stop the war, get down on our knees before them for what we did to them, pay them reparations, and ask them for forgiveness… What do parents tell you when you’re little? Don’t hit someone smaller than you. Don’t take something that doesn’t belong to you. It’s so obvious that Ukraine is weaker and it’s their land.

In the first war I saw, in Karabakh, I realized I was always on the side of the weak… If you are for the weak, you’re for the person who is struggling and suffering. I’m always on the side of the weak.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.