Ten years ago, I had no fears at all. Losing a job? I could find another without any problem. Falling ill? We had health insurance, friends who could help and charitable foundations we could call.

Crime? In Moscow? No way! A return to repression? You must be crazy. World war? Not in a million!

Now, however, a Levada Center survey reports that 62% of Russians are afraid of world war, 58% fear abuses by the authorities and 52% fear a return to repression. In 2008, by comparison, just 30% of Russians feared world war and abuses by the authorities, and only 17% feared a return to mass repression.

People ask me several times whether I am afraid, and the answer is that I am. One-half of my potential campaign donors tell me, “This whole thing is too dangerous”. Many of the experts advising me on the elections are convinced the authorities will jail me.

The time has come to speak openly about our fears and understand how to move on. For that, we first need to understand the facts.

The cold facts

Some fears are rational, but not all. Some people are afraid to fly in airplanes but are not afraid to drive a car or cross the road, although in 2018-2020 in Russia, fewer than 300 people died in plane crashes and more than 50,000 died on the roads.

What is the probability of being persecuted for political reasons?

According to the Memorial human rights organization, Russia has 80 political prisoners (not counting those jailed for their religious beliefs) and another 405 whom the authorities persecute without jailing. Taking as the minimum number of Russia’s politically active citizens the 467,000 individuals who signed up for rallies in support of opposition leader Alexei Navalny, each has less than a 1 in 5,000 (0.017%) chance of winding up in prison, and less than a 1 in 1,000 (0.086%) chance of being persecuted without serving time behind bars. The chances that the authorities will search their home or office is less than 2 in 1,000 (0.17%).

What’s more, this is not an annual probability, but an overall likelihood over a period of years. And this is using the minimum number of political active citizens for our calculations.

For comparison, the Internal Affairs Ministry reports that in 2020, Russians had a 1 in 2,500 (0.04%) chance of dying or being seriously injured as the result of a crime. This figure — for just one year — is double the overall probability of going to prison for political activity over a period of several years. Even the most sanguine citizens might find themselves thinking, “Crime is completely off the scale. It’s time to ditch this country”

Who wants us to fear?

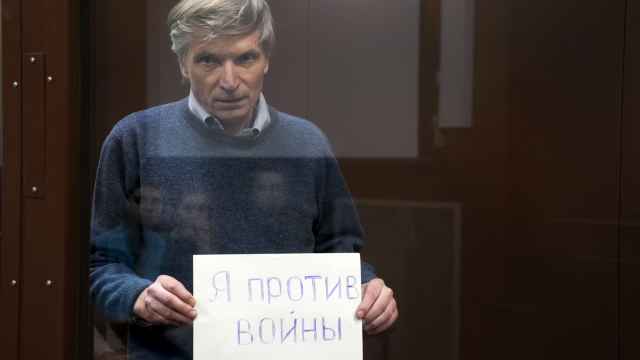

The point of political repression is not to jail every single opposition member and all of their supporters, just as the point of terrorism is not to blow up entire populations. The point is to instill a fear that complicates life for the most active members of society — a strategy that is clearly working against the members of my social circle. This approach also inspires loyalists to call for even harsher repressive measures. According to the theory of regal and kungic societal structures, an atmosphere of danger and conflict pushes society towards strict hierarchy and authoritarianism.

The authorities are deliberately creating just such an atmosphere.

How? On the one hand, they bring high-profile criminal cases against those protesting official corruption or else label Navalny’s Anti-Corruption Foundation an extremist organization. On the other hand, the daily news depicts made-for-TV moments in which police officers confront individual protestors ostensibly taken at random from the crowd.

At this point, the so-called “Crimean consensus” — that is, popular support for the ruling authorities after the annexation of Crimea — has completely unraveled. The economic stagnation and recession have continued for seven long years, and ruling officials offer no clear plan for pulling the country out of the quagmire. Neither can Russia’s “leadership” offer any sort of attractive image of the future. In one Russian town, the people even preferred voting a cleaning woman with a good reputation into office than a candidate from the ruling party.

It seems that the authorities have resorted to inducing widespread fear as a means to holding onto power. However, recognizing that this is their strategy is the first — but not the only — step to defeating it

A Russian version of this article was first published by VTimes.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.