On April 21 the Museum of Russian Impressionism has mounted another exhibition filled with revelations. Called “Seekers of Art,” the show continues the museum’s innovative approach to uncovering the hidden aspects of Soviet life. It tells about a phenomenon that before perestroika was not publicized and in fact was harshly punished: private collections of art, especially painting.

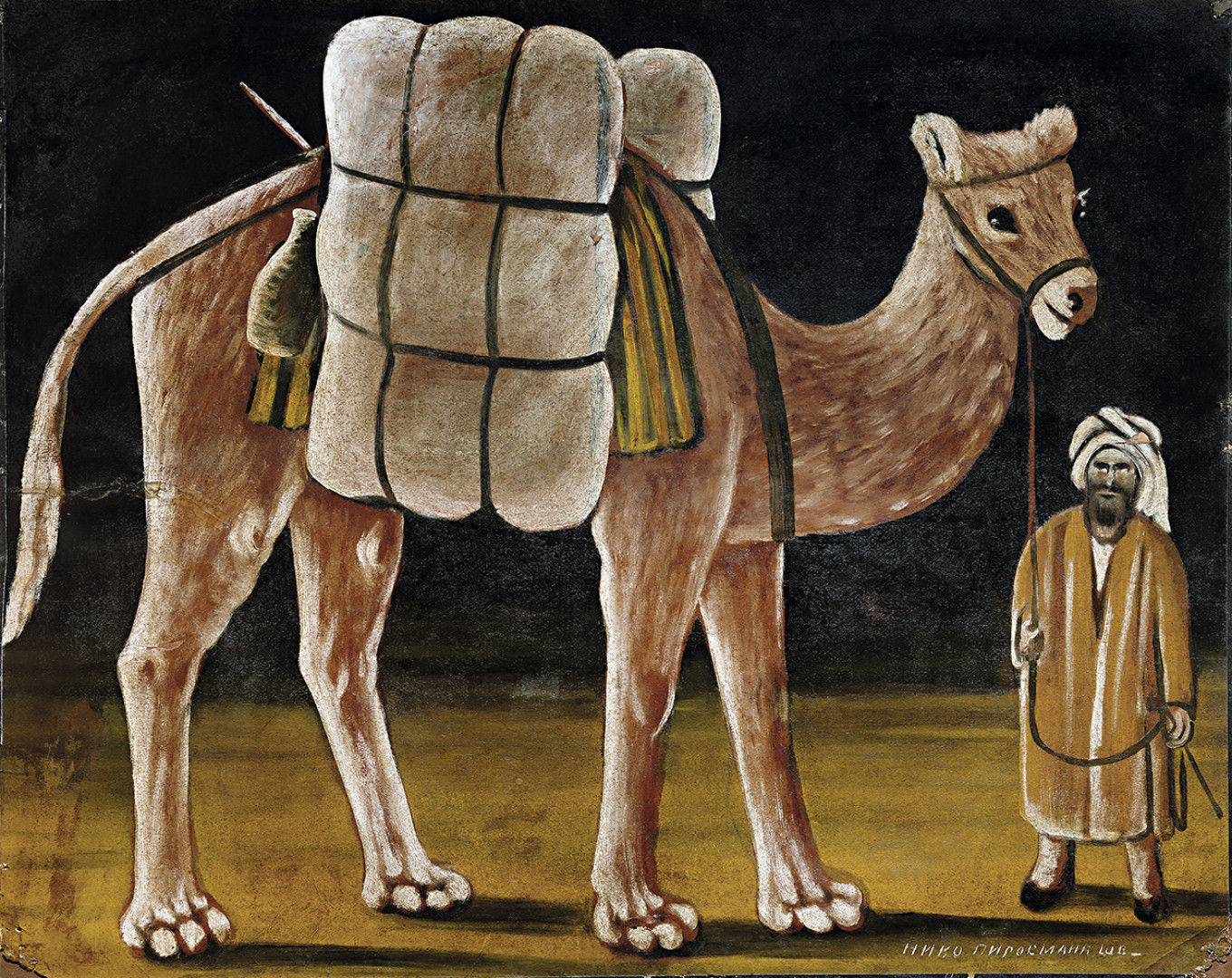

The show displays works from private collections: works by Nikolai Roerich and Konstantin Korovin, Niko Pirosmani and Kazimir Malevich, Robert Falk and Pavel Kuznetsov. But the focus of the show is not the rich art collections on display but the extraordinary collectors. Most of them were the elite of the “classless Soviet society” – famous doctors, scholars and diplomats who didn’t always have to follow the rules. Some of them, especially the engineers and scholars, fell under the steamroller of Stalin’s repressions, but they lived to continue to collect art.

As the exhibition curator Anastasiya Vinokurova said at the opening, the organizers present a snapshot of a strange phenomenon — art collecting in a society where there was no private ownership and “speculation” (buying from an individual) was illegal.

None of the collectors were interested in socialist realism. They all sought out the so-called formalists – artists who had been crossed off the lists of official Soviet art. That is, these collectors had good taste and knew something of true value when they saw it.

The collectors do indeed deserve our attention. They rescued works from the early 20th century, a period not far in the past but almost forgotten at the time. Each collection is prefaced by a helpful and witty introduction: graphic portraits of the collectors done by artist Maria Ponomareva and short biographies written with a light touch by art specialist Sofia Bagdasarova.

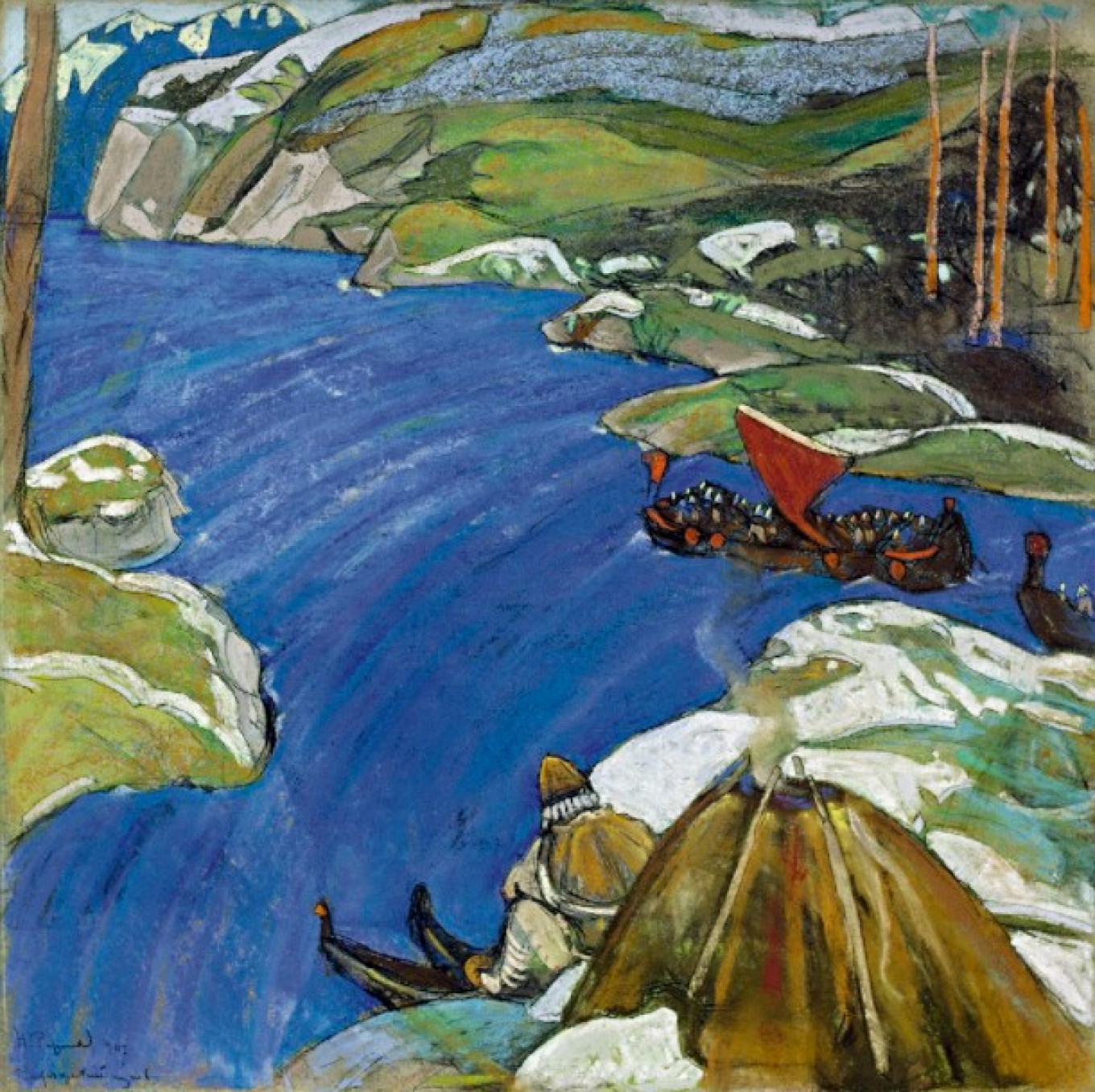

There are 14 collectors and their works on display. The best known is Aram Abramyan, the chief Kremlin urologist who treated the Soviet leaders and was therefore somewhat protected from attacks by the Soviet regime. His collection includes works by Alexander Golovin, Boris Kustodiev and a portrait of a woman by Konstantin Korovin. Another prominent collector is Alexander Myasnikov, the legendary doctor who is said to have treated Stalin. He collected works by Nikolai Roerich and Mstislav Dobuzhinsky.

The St. Petersburg gallery KGallery brought works from private collections in the northern capital. Gallery representative Kristina Berezovskaya called Soviet private collections “art behind locked doors.” The St. Petersburg historian Sigismund Valk acquired particularly fine self-portraits by the artists Alexander Golovin and Kuzma Petrov-Vodkin. Dmitry Likhachev, the patriarch of Russian culture, called Valk “a true St. Petersburg member of the intelligentsia,” who combined “boundless curiosity with a profound and sharp-witted intelligences and heartfelt kindness.” In Leningrad after the war Valk bought works by Benois, Somov, Mitrokhin, Sudeikin, Serebryakova, Sapunova, Petrov-Vodkin, and Chagall, spending on art the money he had left over from buying books. His collection consisted of about 100 artworks. When he was taken to the hospital at the end of his life, he bequeathed his collection to his student, Nadezhda Simina.

One of the highlights of the exhibition is a work from St. Petersburg by Boris Grigoryev, one of the most mysterious Russian artists from the early 20th century whose works are now hunted down by contemporary collectors. “Portrait of a Woman. Dushka” was painted in 1917 and is now in the private collection of film director Solomon Shushter.

The allure of the half-forbidden art on display illustrates the hypocrisy of Soviet life and the chasm between myth and reality. Most of it has been exhibited quite rarely, such as Grigoryev’s painting “In the Caberet,” painted in 1913.

Vladimir Semyonov, the deputy minister of foreign Affairs of the U.S.S.R. (1955-78) and High Commissar of the U.S.S.R. in occupied Germany, who has gone down in history for putting down the protests in East Germany in 1953, had three paintings by Pavel Kuznetsov. Alexei Stychkin, a simultaneous interpreter who began his career at the U.N. and was married to the famous Bolshoi Theater ballerina Ksenia Ryabinkina collected works by Mikhail Nesterov and Aristarkh Lentulov.

Paintings from the collection of Nikolai Timofeyev, the chief military psychiatrist during the Soviet period, are particularly interesting. As noted in his biography: “He held a very high and dangerous position that became even more complicated in the 1950s and 1960s when Timofeyev was asked to evaluate the mental state of dissidents. Some of them said that he helped them a great deal. Others believe that Timofeyev should be considered a practioner of punitive psychiatry.”

One of the fine paintings from Timofeyev’s collection is called “Frankincense” by Nikolai Kalmakov, which is now held by the KGallery. Kalmakov, an artist long in the shadows, painted fantastical scenes and mythical characters.

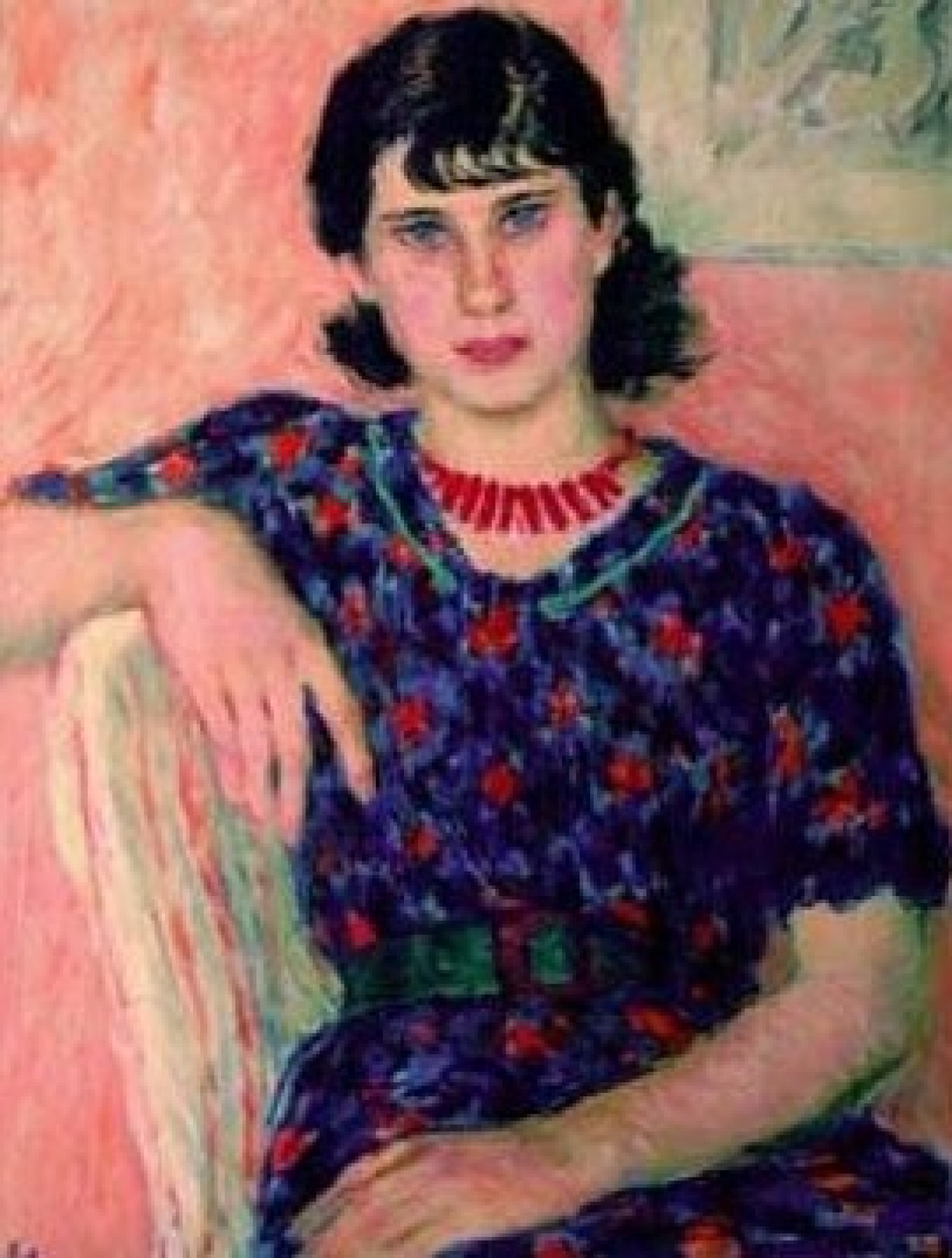

The KGallery also brought to Moscow works by Vladimir Lebedev, a wonderful graphic artist who had been condemned as a formalist and "bad artist" during the Stalinist era. His extraordinarily expressive “Portrait of a Girl with Bangs” (1938) mesmerizes everyone who stops before the painting. It is from the collection of Igor Afanasyev, one of the pioneers of the Soviet petrochemical industry. During WWII Afanasyev was held in a “sharashka,” a special NKVD prison for specialists intended to keep them from being sidetracked from work.

While he was imprisoned near Perm, Afanasyev developed antifreeze and recoil fluid for tanks. When he was arrested in 1937, his first collection — which he had put together over 10 years — was confiscated. When he was released in 1946, he returned to Leningrad and began to collect paintings again. After three years Afanasyev was arrested again, but this time he had hidden his collection. He was sent to Norilsk in permanent exile, where he proved himself as a brilliantly inventive metallurgist. In 1956 Afanasyev was rehabilitated and returned to Leningrad, where he reclaimed his hidden collection and began collecting again.

“For the collectors in our exhibition, adding to their collections was an attempt to create their own worlds, which were an alternative to Soviet reality,” the Museum curators write. “As the economist Yakov Rubenshtein said, ‘I began to collect paintings in 1953 to mark the death of Stalin.’ That event was not only a sign of better things ahead for collectors, but also less danger for anyone infected by the ‘collecting bug’.”

The main painting in the second hall of the exhibition is “Herder with Camel” by Niko Pirosmani from the collection of Igor Sanovich, a specialist in Persian culture. Before Sanovich acquired the painting, it belonged to Viktor Goltsev, the editor-in-chief of the journal “Friendship of Nations,” a specialist in Georgian literature who called himself a “Georgian of the Moscow branch.”

The curators have created a beautifully organized exhibition that warrants a long and attentive visit. They included, not without humor, a series of black and white photographs by the “chronicler of the late Soviet epoch,” Alexander Palmin, which remind museumgoers of the impoverished and gray Soviet life that these collectors lived in as they sought out vibrant artistic impressions and the chance to put their unpredictable Soviet rubles into something eternal. Today these works are sold at auctions for astronomical sums. But even when these art hunters were buying art, the price might have been half the cost of a Volga or Moskvich car.

Concurrent with this show, the Museum of Russian Impressionism has mounted an exhibition in honor of their fifth anniversary. The show looks back at past exhibitions and includes canvases by Yuri Annenkov and Sergei Vinogradov, Nikolai Feshin and Pavel Benkov. It also has on display paintings from the collection of the renowned musician Vladimir Spivakov — works by Boris Chaliapin, the son of the great Russian bass Fyodor Chaliapin, who created the covers of Time magazine during WWII.

The show will run until August 29. For more information about tickets (for specific time periods) and the museum, see the site.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.