Earlier April, the U.S. announced sweeping measures against Russia for a series of “harmful foreign activities” — election interference and disinformation campaigns in the U.S. and elsewhere, the SolarWinds cyberattacks and Russia’s ongoing occupation of Crimea, among other transgressions. The sanctions are partially overdue from the Trump administration and include asset freezes and visa restrictions against a broad array of Russian-affiliated persons as well as more restrictions on Russian sovereign debt. In response, Russia swiftly introduced a broad retaliatory package of its own.

Behind the façade of seemingly yet more symbolic sanctions, there is strategic calculus on both sides to create a framework for deterrence.

It would be wrong to dismiss the latest U.S.-Russia exchange of reciprocal sanctions as insignificant.

Laying the groundwork

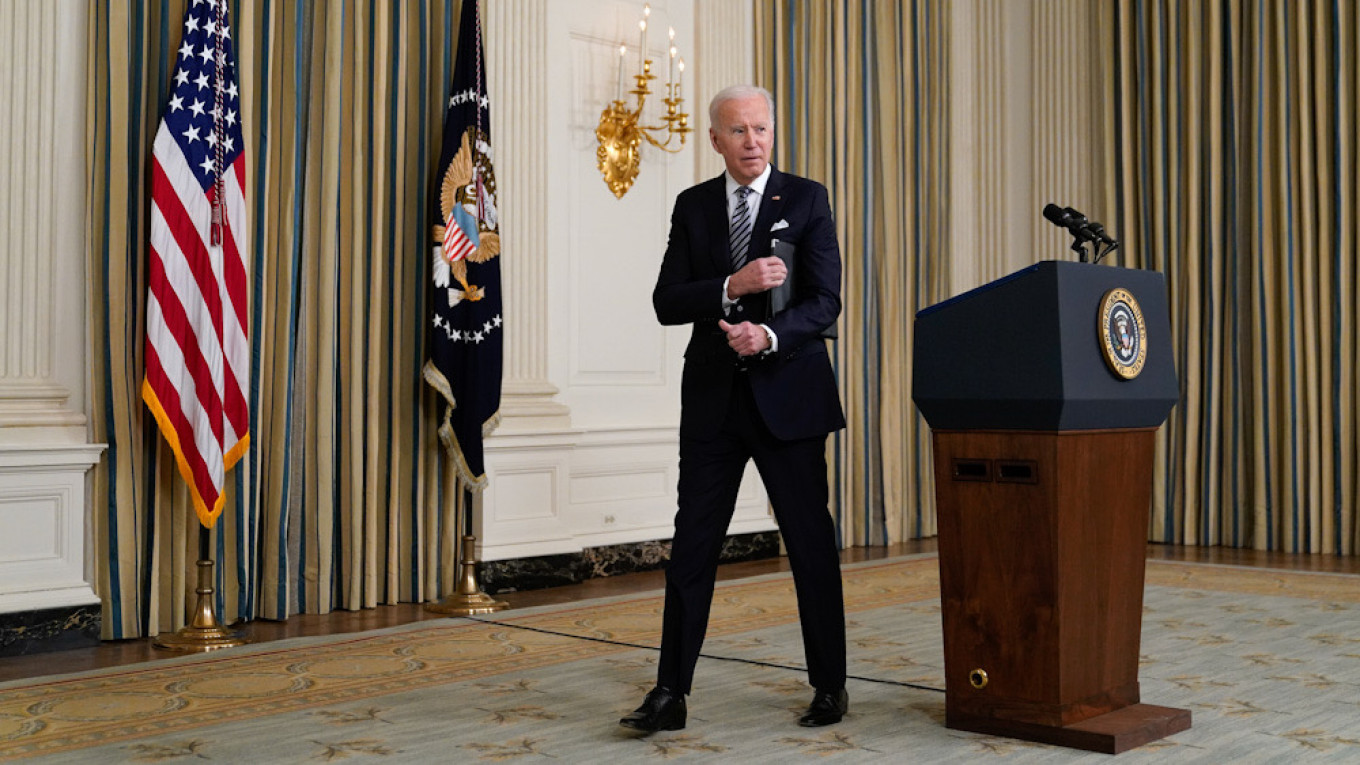

The latest U.S. measures were imposed under a new Executive Order (EO) which lays important groundwork for future actions. The order equips the Biden administration with a great degree of flexibility — a broad framework of sanctions which can be imposed in an expansive manner, depending on how future events unfold.

There are many avenues through which sanctions can be tightened. The EO provides authority to expand sovereign debt sanctions, if necessary, for instance. New sanctions on people who operate, or have operated, in the technology and defense sectors of the Russian economy can be introduced. It also leaves broad room for interpretation over how to define the “technology sector” and what “operate” or “operated in” exactly mean. While it does not explicitly mention the Nord Stream 2 pipeline, the EO does include a provision that a Russian individual or entity responsible for — or complicit in — cutting or disrupting gas or energy supplies to Europe, the Caucasus, or Asia, can be targeted.

The EO is also somewhat similar to previous legislation — the Countering America’s Adversaries Through Sanctions Act (CAATSA) — adopted in August 2017, in that it lumps together wide-ranging transgressions under one umbrella.

That means the possible reasons under which the U.S. could levy sanctions against Russia are versatile and encompassing. They include undermining the conduct of free and fair democratic elections, facilitating malicious cyber activities, using transnational corruption to influence foreign governments or undermining security in regions important to U.S. national security. That suggests it could be hard to delineate them, hold Russia accountable and lift them if there is indeed compliance.

Unlike CAATSA, the new EO does not require congressional review to terminate sanctions, thus giving the Biden administration full control over the decision-making.

The Kremlin wasted no time in its response, swiftly preparing its own package of wide-ranging retaliatory sanctions. The set of measures may pale in comparison, but their aim is to hurt U.S. interests where they can. As there are few options where Russia can inflict pain on the U.S. economically, the majority of measures are of a diplomatic nature and are designed to shrink the U.S. diplomatic footprint in Russia.

Sending signals

With the more moderate measures which were immediately announced, the Biden Administration aimed to strike a delicate balance between sending a strong message of deterrence to Russia while keeping relations from deteriorating further. The markets expected an escalation of sanctions against Russia, but instead Biden signalled that he wants stability and predictability in their relationship. The U.S. aimed to deliver the message to Moscow that it was prepared to “impose costs in a strategic and economically impactful manner” if it continues its destabilizing international actions.

As Russia has announced a partial withdrawal of its troops from the Ukrainian border, the message seems to have been well understood, at least for now.

It is true that this first batch of U.S. sanctions was not as severe as anticipated. For instance, the threat of sanctions on Russian sovereign debt had more impact than their actual imposition. The share of non-residents holdings of Russian bonds had already fallen from 35% to around 20% by the end of March, before the sanctions were announced. In prohibiting the purchase of ruble-denominated Russian state debt, the Biden Administration only slightly expanded the preexisting restrictions against buying non-ruble bonds. Trading on the secondary market was not targeted, neither were Russian state-owned banks banned from participation.

In a tit-for-tat fashion for U.S. sanctions imposed over jailed Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny, the Kremlin issued visa bans on eight current and former U.S. high-ranking officials, including FBI Director Christopher Wray, Director of National Intelligence Avril Haines, U.S. Attorney General Merrick Garland and the former U.S. National Security Advisor John Bolton. Another 10 American diplomats were expelled from the country. The U.S. ambassador John Sullivan was strongly recommended to return home for consultations.

Flexing its muscles on the Ukrainian border was another part of Moscow’s asymmetric response. The military buildup in eastern Ukraine and in Crimea was in part to send a signal of deterrence to Washington for its new sanctions. At his annual state of the nation address on April 21, Russian President Vladimir Putin indirectly referred to the U.S. sanctions as “unlawful, politically motivated” and alluded to them as part of a “crude attempt to enforce its will on others.” Putin warned of a “asymmetrical, rapid and harsh” response, if the West crosses a red line. As Mr Putin's spokesman Dmitry Peskov clarified later, those “red lines” are Russia’s external security interests and interference in domestic processes.

Growing tougher

All this means that the next round of reciprocal sanctions is likely to be tougher.

The Biden Administration can always impose another batch of signalling sanctions, but there are limited options for soft sanctions to act as a deterrent.

Currently, the U.S. administration is evaluating the impact of its sovereign debt sanctions on Russia and is prepared to ramp up the pressure. The second round of sanctions, specifically related to Navalny — under rules against the use of chemical weapons — is due early June and could include new penalties against Russian bonds. There are already rumors that the next expansion could bar U.S. financial institutions from the secondary market for ruble-denominated bonds.

Such measures would have much stronger repercussions that the first round — as the overwhelming majority of foreign investors are engaged in secondary trading. Americans are the largest non-resident holders of Russia’s state debt, amounting to around 7% of the total. At the same time, the Biden Administration wants to avoid any unintended consequences, akin to Trump’s sanctions on Oleg Deripaska’s companies in 2018 which rocked global markets. The U.S. Treasury is currently conducting a review of financial sanctions to ensure that they are fit for purpose and can remain a strong and viable policy tool.

Equally, Russia has other options up its sleeve. Moscow claims to have prepared an array of “painful decisions,” including economic sanctions and shrinking the U.S. diplomatic representation if Washington continues down its “confrontational course.” Other options include the termination of the Memorandum of Understanding on Open Land signed in 1992 which allows U.S. diplomats to travel across Russia without prior notice. More importantly, the Russian Foreign Ministry warned that it could also end the activity of American foundations and NGOs, which it believes interfere in Russia's internal affairs.

While U.S.-Russia relations are back to the status quo ante, both parties reserve options for further escalatory measures — either economic or military.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.