What is more comforting than a bowl of matzoh ball soup? Is there another elixir that can vanquish the blues, kill a cold, warm up the body, or nourish the soul quite like it? Does your spirit not rejoice when a large soup plate is set in front of you: a rich golden chicken broth with hints of fresh herbs, lemon, and pepper, carrots bobbing up and down, all swirling around the main event — larger than a golf ball, but smaller than a baseball — the matzoh ball?

Today the matzoh ball comes into its annual headliner role as the centerpiece of the Passover seder. This weeklong Jewish holiday commemorates the liberation of the Hebrew slaves from Egypt and their deliverance from the last and most devastating of the Ten Plagues of Egypt, when the Lord “passed over” their houses even as he slaughtered each firstborn in the land.

The food of Passover seder is highly symbolic: eggs symbolize spring and renewal; haroset — a paste made of wine, nuts, and apples — is symbolic of the mortar the Jews used in building the pyramids of Egypt; bitter herbs represent the pain of slavery; and matzoh represents the unleavened bread the Hebrews took with them as they fled Egypt, led by Moses to the Promised Land. While Passover food can vary depending on each family’s tradition, matzoh ball soup is one of the most popular dishes in the Ashkenazic (Eastern European Jewish) tradition.

For the duration of Passover, to honor the trials of their ancestors, and commanded by God in Exodus 12:14: “You shall eat nothing leavened; in all your dwelling places you shall eat unleavened bread,” Jews refrain from eating anything with yeast or anything resembling bread such as cakes and cookies, and instead eat flat, cracker-like matzoh.

When the Jews migrated to Eastern Europe, they discovered and adopted that region’s popular dumplings, known as knödel, or in Russian klyotska, and these words lent their vowels and consonants to the word for dumpling in German-Yiddish, knaidel (or kneydl). During Passover, Jews made their knaidel dumplings out of matzoh to adhere to the dietary strictures of the holiday, and when they were forced to flee another authoritarian regime in the nineteenth century, they took matzoh and knaidel with them, where are still enjoyed today in delis all over the North America.

Matzoh went mainstream in the nineteenth century thanks to a Lithuanian rabbi called Abramson, who assumed the identity of a dead man to avoid military conscription in the Russian empire. The rabbi became Dov Behr Manischewitz, and after emigrating to the United States, he started manufacturing matzoh in Cincinnati. Thanks to savvy marketing, very soon matzoh wasn’t just for Passover anymore.

I consider myself something of a connoisseur of matzoh ball soup, one of my main sources of sustenance as an undergraduate in New York City. I spent many happy Sundays trawling the five boroughs in search of the ultimate matzoh ball experience: from Katz’s to Barney Greengrass; 2nd Avenue to Brooklyn Diner; The Carnegie Deli to Sarge’s — I never did settle on a winner, but I make return quality control visits whenever possible to consider the relative merits of each deli. I’ve also had truly innovative matzoh ball soups in Prague, Vienna, Budapest, and Tel Aviv, and Jerusalem. Each place puts its own stamp on the dish, like a dash of paprika in Budapest, or a hint of mint in Jerusalem.

Like its German and Russian cousins, matzoh balls are soft, pliant dumplings, but while knödel and klyotska are often stuffed with meat, smothered in gravy, or used to stretch a hearty stew, matzoh balls are most often floated in broth. They are just as easy to make as their Eastern European counterparts — by combining matzoh meal, eggs, and… well, then opinion divides, and fights break out over the remaining ingredients. The challenges here are twofold: one, to adhere to Jewish kosher laws which forbids serving meat and milk products together, making it impossible to use butter, cheese, or cream to bind the dumplings. Passover forbids using yeast or anything like it, including baking powder, which could make the dumplings a desired light, pillowy airiness.

And so, the debate rages through the Jewish world: how to make the best matzoh balls while remaining compliant with religious and dietary laws, and preferences? Do you want a “sinker” or a “swimmer,” a denser matzoh ball that absorbs the broth and sinks to the bottom of the pot after it’s been cooked, or a “swimmer” that bobs on the surface?

To answer these questions, I spent several happy afternoons in the kitchen testing different authorities from Claudia Roden to my friend Avi’s Aunt Shirley. I concur with the notion that chicken schmaltz or rendered chicken fat is key to both flavor and texture. Whipping some egg whites makes for a much lighter ball, and the longer rest of the dough greatly adds to the consistency and texture. I agree with the increasingly popular notion that you need some flavor in a matzoh ball — though it should be complimentary to that in the broth. In the recipe below, I’ve gone with white pepper and turmeric and lots of fresh herbs. One trick that is often whispered in the ears of would be matzoh ball soup makers is to use seltzer rather than water, but I’ve always used ginger ale because someone, somewhere once whispered that in my ear, claiming all manner of magical properties that would make my matzoh balls so light they might even take flight like a balloon. And who am I to argue with magic?

As I was recipe testing, Jenn Louis’s authoritative and addictive “The Chicken Soup Manifesto: Recipes From around the World” arrived on my desk, containing two fantastic matzoh ball soup recipes. Her suggestion to leave the balls in their poaching liquid but off the heat for some additional time has forever laid to rest the sinker versus swimmer feud: using Louis’s method, these matzoh balls sink, then swim, then sink again, having absorbed lots of their liquid. Perfection.

Chag Pesach Samech to all celebrating Passover this week!

Research into the history of matzoh in America from Gil Marks’s “Encyclopedia of Jewish Food.”

Herby Matzoh Ball Soup

Ingredients

For the matzoh balls

- 1 ⅓ cup (315 ml) matzoh meal

- 5 eggs (separate 3 of them into yolks and whites)

- ⅓ cup (80 ml) schmaltz (rendered chicken fat), melted and cooled

- ⅓ cup (80 ml) ginger ale

- 1 tsp salt

- ½ tsp turmeric

- ½ tsp white pepper

- 1 Tbsp finely minced chives

- ¼ cup (60 ml) finely minced parsley and dill

For the soup

- 1 lb (500 grams) chicken wings

- 2 bone-in, skin-on chicken breasts

- A bouquet garni: thyme, rosemary, and parsley tied together or wrapped in cheese cloth

- 2 bay leaves

- 2 Tbsp olive oil

- ⅓ cup (80 ml) apple cider vinegar

- 1 knob of fresh ginger cut into coins

- 2 pieces of fresh turmeric, cut lengthwise

- 1 yellow onion, cut into quarters with the skin still on

- 1 Tbsp whole cloves

- Salt and peppercorns

- 3 carrots peeled and sliced into rounds

- ½ cup (125 ml) finely chopped herbs such as parsley, basil, dill, and thyme

Instructions

Make the soup

- Rinse the chicken breasts thoroughly, then add them to a large, heavy-bottomed soup pot or Dutch oven, and add enough cold water to cover them by 2 inches (about 3 liters/quarts). Add 2 Tbsp salt, the bay leaves and the bouquet garni with a tablespoon of freshly crushed peppercorns and bring to a slow simmer. Skim any accumulated foam from the surface with a slotted spoon. When the water is just coming to a boil, remove the pot from the heat, cover, and poach the breasts for 90 minutes — 2 hours.

- Remove the chicken breasts from the liquid with tongs and strip the meat from the bones and skin. Don’t worry if the meat seems slightly underdone: it will finish in the soup. Place the meat in an airtight container and refrigerate until you are ready to assemble the soup.

- Pour the remaining liquid, skin, bones, bay leaves, and bouquet garni into a large bowl. Wipe out the soup pot and return to the stove. Heat the olive oil over medium-high heat, then sear the chicken wings for 3-5 minutes until they develop a nice deep golden-brown color. Flip the wings and sear them on the other side for 2-3 minutes.

- Add the poaching water, chicken bones and skin, bay leaves, bouquet garni, apple cider vinegar, ginger, turmeric, onion, and cloves and stir to combine. Bring the pot to a slow boil, then lower the heat, cover, and let simmer on the lowest possible heat for 2-3 hours.*

- When the broth has simmered, strain it through a fine-mesh sieve or a colander lined with several layers of cheesecloth. Discard the solids. Taste the broth and adjust seasonings with more salt and pepper if needed. Then let the broth rest overnight. You can remove the accumulated fat from the surface if you wish or leave it there.

Make the matzoh balls

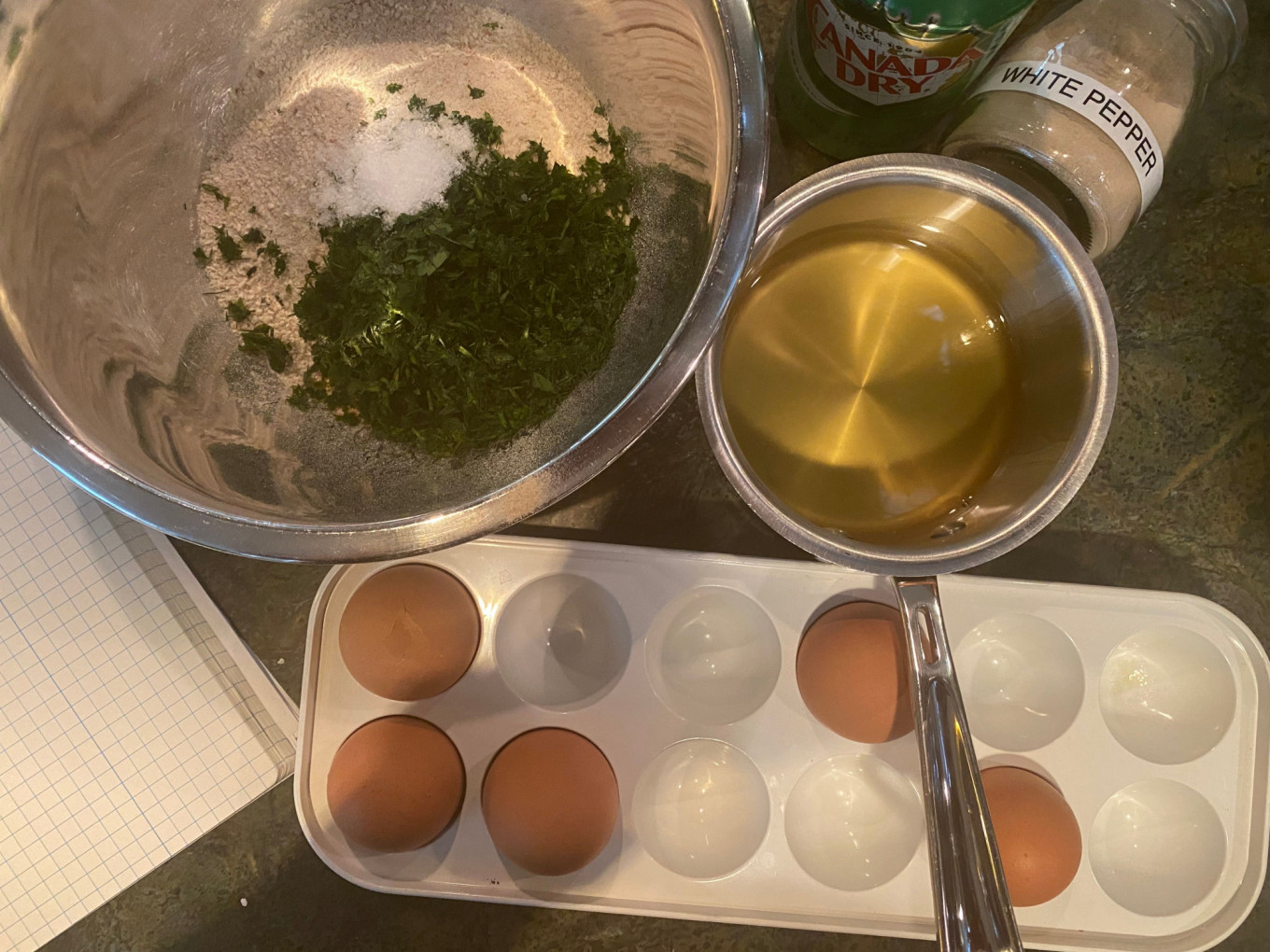

- Combine the matzoh meal, chopped herbs, salt, white pepper, and ground turmeric together in a large bowl.

- Separate three of the eggs and add their yolks to the remaining two eggs. Set the three egg whites aside. Add the ginger ale and melted schmaltz to the egg mixture and whisk briefly to combine.

- Whip the three egg whites until they form stiff peaks. Fold them into the egg yolk mixture, then fold this mixture into the dry ingredients. Do not over mix.

- Press plastic wrap against the matzoh ball mixture and refrigerate for at least 1 hour and up to 4 hours.

Assemble the soup

- Simmer the carrots in the chicken broth until they are pliable.

- Bring a large pot of cold, well-salted water to a rolling boil.

- Form the matzoh mixture into golf-ball sized balls, then drop them carefully into the boiling water. Cover the pot, lower the heat, and let the balls simmer for 30 minutes without removing the lid. After 30 minutes, remove the pot from the heat and let the balls rest in the liquid for an additional 30 minutes.

- Shred the poached chicken breasts and add the meat to the soup pot and warm through. Just before serving, add the chopped herbs.

- When the matzoh balls are ready, place one or two to each bowl, then ladle the hot chicken soup broth around the balls. Serve immediately.

*If you have a slow cooker or Instapot, use them to make the broth — their ability to maintain a steady low temperature is ideal for this kind of “low and slow” broth.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.