Халтура: a funeral (camp slang)

It is very rare that I get to combine my two favorite pastimes: going to museums and studying the Russian language. But this week the Gulag History Museum in Moscow opened an exhibition called “The Language of [Un] Freedom” dedicated to a new dictionary of camp slang, and I was almost first in the door.

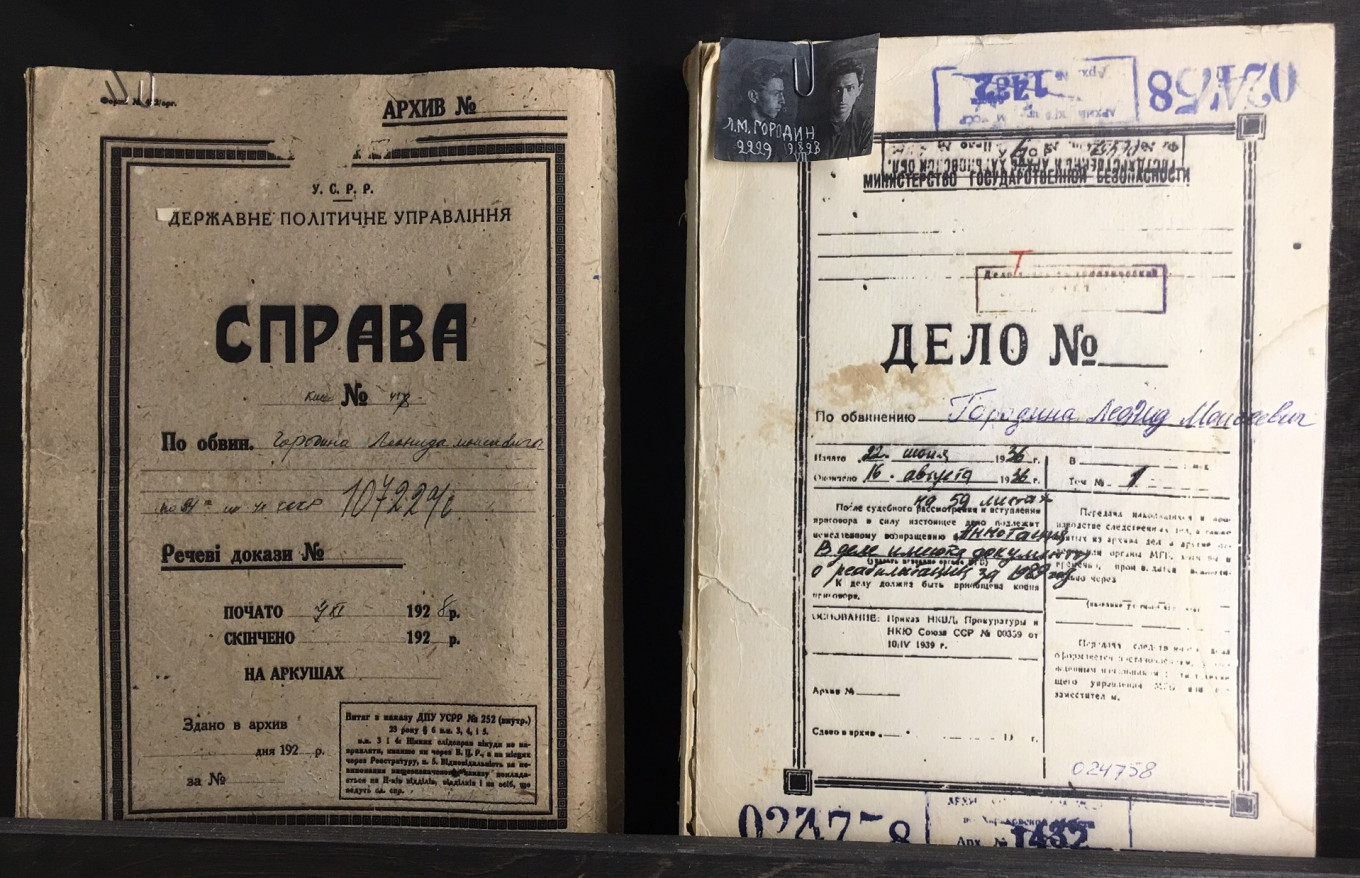

The exhibition illustrates and celebrates the newly published “Dictionary of Russian Slang Expressions: The Lexicon of Penal Servitude and Camps in Imperial and Soviet Russia,” more commonly called Gorodin’s Dictionary after its compiler, Leonid Gorodin.

Gorodin (1907-1994) was a worker, Komsomol and then Communist Party member who had the misfortune of passing around “Lenin’s will” with the first Soviet leader’s criticism of Stalin. He was arrested in 1928 and spent 15 years in various camps around the country. When he was released, he wrote a collection of short stories about his fellow inmates and realized that the general reader needed help understanding their speech and, indeed, their lives. He spent 20 years working on his dictionary, which he typed up and bound in four red volumes. But he did not live to see it through the process of editing and publication.

The published volume has 17,000 carefully annotated entries along with additional biographical materials and essays as well as camp proverbs, songs, poetry, sayings and examples of usage in prose. It is, as curator Tatiana Polyanskaya said, an essential guide for anyone reading literature from and about the Gulag.

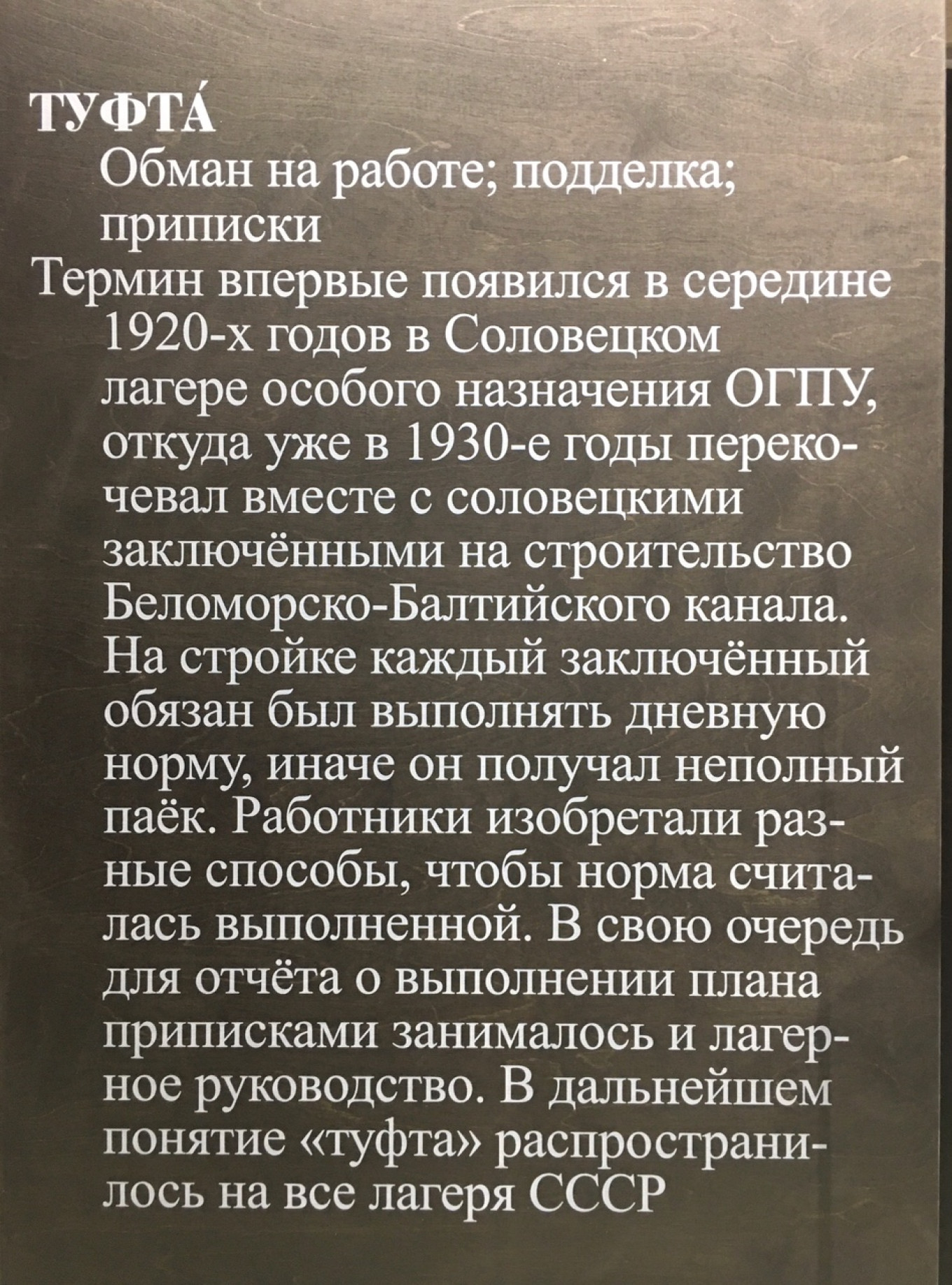

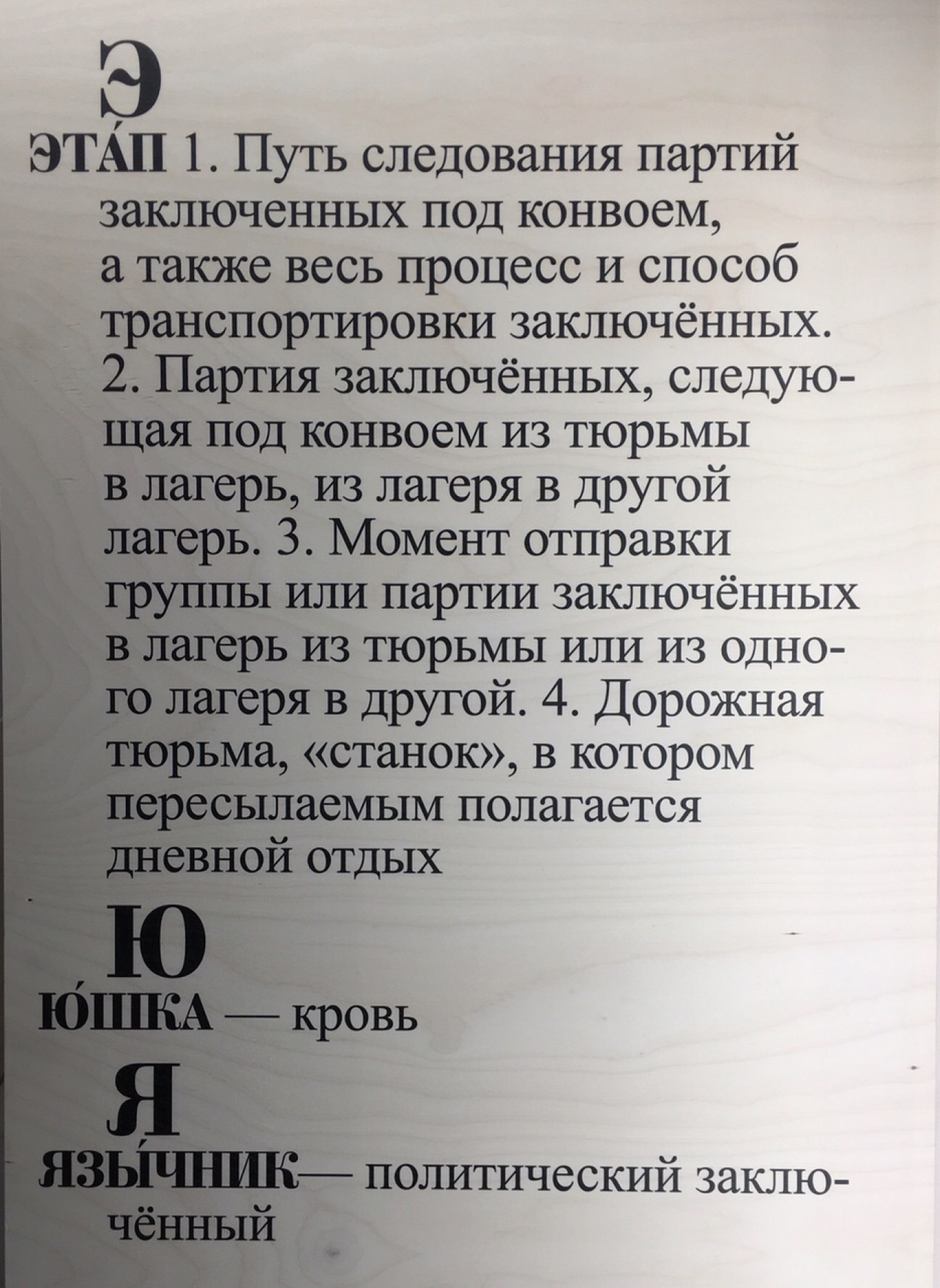

The language is surprising rich. “People came to the camps from all over the Soviet Union,” Polyanskaya said, “and many rivers of language flowed into the system with them: criminal slang, regionalisms, archaic words that had survived in villages, Yiddish and bits of other languages. The prisoners needed to create their own language to describe their reality.”

The camp language lesson begins at the start of the exhibition with зек (prisoner, inmate, convict). The word appeared in one of the first work camps that was opened in the 1930s to build the Belomor-Baltic Canal. In the doublespeak of the time, a canal worker — that is, a prisoner sentenced to hard labor — was called каналоармеец (canal soldier), a part of the great army of workers battling the elements to build a bit of the socialist state through the inhospitable northern forests. In official Gulag documents, one of these first prisoners was з/к — заключённый каналоармеец (a prisoner canal soldier), which was first pronounced as the letters in the abbreviation “зе ка” (ze ka) and then was shortened to зек.

After the bulk of that canal work was done, most of the prisoners were sent on to work at other camps around the country. The word зек, once a site-specific word, traveled with them to other camps and came to mean a convict in general.

As I went through the exhibition and then started reading the dictionary, I was struck by how many words I use today that came from the Gulag. I thought гулять in the sense of to go off drinking, to party, was “regular” slang, but it’s not. Женщина гуляет or она — гулящая means that the woman is a prostitute. In English, it’s the opposite — she’s not having fun, she’s a working girl.

Similarly, I didn’t think алкаш was a nice word for an alcoholic, but I had no idea it came from the Gulag. Or how about this: Я так устал! Пойду домой и вырублюсь (I’m exhausted! I’m going home and crash.) Вырубиться also comes from the camps, from the image of рубильник (master switch) and вырубить ток (cut off the electricity). Or this: Если я потеряю её кольцо — мне хана! (If I lose her ring, it will be the end of me.) Хана (death, destruction) like крах (failure) and лажа (rubbish, total crap) are camp slang.

Чапать is an archaic word that got a new meaning in the Gulag. In old dictionaries it means to grab or touch something, but in the camps it came to mean to walk. Out of the camps today it means to trudge: Если сейчас денег не дадут, чапать мне через всю Москву пешком (If they don’t give me the money now, I’ll have to trudge on foot all across Moscow.)

And then somehow some English entered the Gulag with трузера (trousers).

But most of the time the surprise is seeing common Russian words with new meanings. Some are rather witty. For example, трудиться, which out here means to work hard and put in effort, means to commit a crime in camp slang. And a труженик (hard worker) is a thief who is constantly working. Makes perfect sense — stealing is hard work.

Халтура remains a mystery to me. In Russian it’s work on the side, moonlighting, or a piece of shoddy work. In camp slang it’s a term for a fancy funeral outside the Gulag.

The camps were also full of animals — or rather people as animals. Пёс (dog) is a naïve person who has no idea he’s dealing with a crook (like a trusting dog), but псы (dogs) are camp guards (like a pack of canines). Краб (crab) is a militiaman, индюк (male turkey) is an police agent put in a cell to gather information, and грызуны (rodents) are children — obviously perceived as pests. Жаба (toad) is used to describe many kinds of people: a detective, a crafty woman, an immoral person, or a convoy guard. But Иваны (Ivans) were the prison aristocrats.

And those are just a few of the thousands of entries.

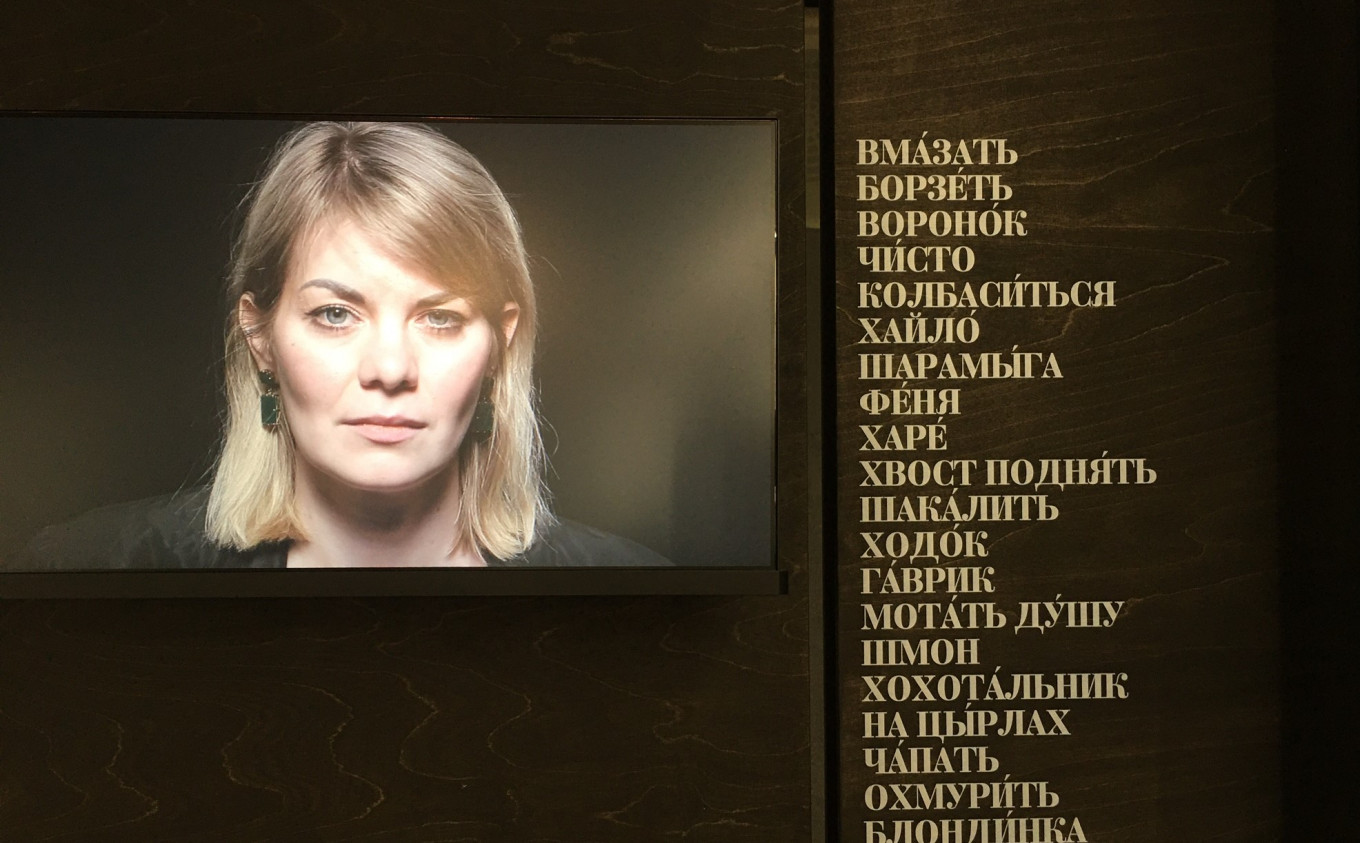

If you are thinking that the exhibition itself might not be interesting — it’s a dictionary; what’s there to see? — you’d be wrong. One side of the room, designed by architect Maya Frolova, has stands that tell the story of Gorodin and his life’s work, with dictionary entries next to the objects they describe and excerpts from letters and literature showing their usage.

On the other side of the room is a wall of enlarged pages from the dictionary partitioned into sections with videos of people — young, old, men, women — taking turns to read out lists of camp slang. While some read, the others seem to wait, staring out at the words and objects, curious witnesses to the world of Gorodin’s dictionary.

For more information and tickets see the museum site here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.