With snow set to be a fixture for much of next week, what’s needed now is an absorbing project to keep us inside — preferably one with delicious results. And for that, you can’t beat a babka! A savory babka with mushroom filling in this case: cake meets bread, and breakfast meets dinner in this yeasty, eggy braided loaf, stuffed with delicious swirls of rich, umami filling.

The babka is one of Eastern Europe’s more tenacious confections, though its origins remain hotly contested. The Poles proudly claim it as their own, noting that the name comes from the Polish word for “grandmother.” That’s a nice thought, say the Italians, who beg to differ: a babka is just a Polish riff on Italian panettone, brought to Poland by the feisty, intelligent, and very wealthy Bona Sforza d’Aragona in the sixteenth century when she married the King of Poland. And the resourceful Ashkenazi Jews of Ukraine will probably just laugh all the way to the spice cupboard; they know that babka is a treat cobbled together from leftover challah dough and any fruit, nuts, or spices lying around.

But what on earth has this got to do with Russia, I hear you cry?

It has everything to do with the marvelously fluid quality of Eastern Europe culture, which seeps across borders, effortlessly absorbs foreign ingredients and influences, and cross-pollinates with neighboring countries in defiance of shifting political boundaries. Ukraine and Poland may be independent nations, and not on the best terms with Russia right now, but both were once part of the sprawling, multi-ethnic Russian empire, and we cannot deny their shared culinary heritage today.

And on a personal note, it has everything to do with a sublime babka stuffed with apricot jam I used to try in vain to resist each time I passed the bakery near my Moscow office.

Perhaps this is the great strength of the babka: its ability to meet the culinary moment and be all things to all people, its resilient tendency to mutate over the centuries to satisfy changing tastes, norms, and the availability of ingredients. We think of babka as inseparable from chocolate, but in the 16th century only someone with Bona Sforza’s wealth could have afforded chocolate, then a rare and luxurious commodity, and certainly not one to be squandered on stuffing for bread. Poles made babka with butter, while Jews used oil in adherence with their dietary laws. And no sixteenth century cook would have dreamt of covering a babka with streusel topping.

I believe all three claimants to babka authorship have merit. Perhaps we should think of this not as a competition so much as a fascinating story of culinary evolution. Imagine Bona Sforza brought a slightly dry yeast bread to Poland. And suppose the Poles found it too dry, so they added jam, poppy seed paste, fruits, spiced sugar, and other sweet delicacies, and rolled these into the dough. Then, as Gil Marks, author of “The Encyclopedia of Jewish Foods” suggests, they baked it in round, fluted cake tins that looked like a grandmother’s skirt. For this reason — and since it was probably the grannies who were making this sweet treat — they named it after “babica” or grandmother. A few centuries later, the exiled King Stanislas of Poland proved equally creative when he steeped a dry French cake in rum syrup to create one of Europe’s most cherished confections, the rum baba, a distant boozy cousin to the more traditional babka, much loved in Russia and across Eastern Europe.

Bona Sforza’s reign coincided with a great flourishing of Jewish life in Poland, thanks to a policy of tolerance by the Polish-Lithuanian monarchs. For this all-too-brief period, Jews lived alongside their Polish neighbors in relative harmony, and a certain degree of cultural exchange was inevitable. Jewish homemakers didn’t use the Polish fluted pans, but they repurposed leftover challah dough into braided loaves, rolled up with raisins, poppyseeds, cinnamon, and sugar, and baked them in bread tins alongside their braided Sabbath loaves.

It was the Jews who took the babka with them when they emigrated to North America after the pogroms of the 1880s and early twentieth century, and later to Israel in the post-war waves of Soviet immigration. The transplanted babka thrived in its new soil, acquiring attributes such as streusel toppings and new fillings of chocolate ganache and almond paste. And if, by the end of the turbulent 20th century the babka was considered slightly old world and unfashionably ethnic, it took only 23 New York minutes to bring it roaring back into fashion when Jerry Seinfeld and his girlfriend Elaine (Julia Louis-Dreyfus) came to blows in a bakery over the last chocolate babka in “The Dinner Party” (Seinfeld, 1994). This is certainly how I discovered it. Then Nutella, the delectable Italian chocolate hazelnut spread, went mainstream, and savvy bakers started putting that into babkas. And just like that, the babka was back.

My first experience with savory babka was in Israel, where babka is almost a national dish. I chose one filled with soft cheese and spiked with za’atar in Jerusalem’s Old City. And I was delighted, though not surprised, to discover the baker spoke fluent native Russian when I sought entrance to his kitchen in search of a recipe.

Since then, savory babka has been a fixture in my baking rota. And with good reason; this delectable eggy, yeasty bread, marbled with savory fillings such as olive tapenade, fresh herb pesto, cheese, or mushrooms can take on breakfast, lunch, dinner, or midnight snack with equal ease. Toast from it is outstanding, smeared with goat cheese, butter, or cottage cheese. Serve it with a bowl of soup or alongside salad and you have a meal. When in doubt, throw a poached egg on it!

The recipe below is a babka customized to Russia’s own national culinary obsession, the mushroom. These are sautéed in butter, then processed with ricotta and fresh herbs. As always, I encourage you to experiment and with that in mind, there are three suggestions for alternative fillings at the end of the recipe. However you choose to stuff it, you’ll get a swoon-worthy babka at which no Italian queen, Polish king, or Jewish homemaker would turn up her nose. This dough is easy to handle, and rises three times, including a long overnight session in the refrigerator, making this the perfect weekend project for a delectable babka you simply can’t beat.

Mushroom Babka

Ingredients

Babka Dough

- ⅔ cup (160 ml) milk, warmed to about 110ºF

- 1 package active dry yeast (2 ¼ tsp, 7 grams, 11 ml)

- 2 Tbsp sugar, divided

- 3 ½ cups (590 grams) flour and more for dusting

- 1 ½ tsp kosher salt

- 4 large eggs at room temperature

- 6 Tbsp (85 grams) unsalted butter, divided into small cubes and softened to room temperature

- Olive oil

Mushroom Filling

- 1 ½ Tbsp unsalted butter

- 1 lb (453 grams) fresh mushrooms, cleaned and thinly sliced (white, Portobello, or chanterelles work well in this recipe)

- 1 tsp kosher salt

- ⅔ cup (160 ml) ricotta, drained of its whey

- 1 tsp nutmeg

- 1 Tbsp soy sauce

- ⅓ cup (80 ml) hard cheese such as parmesan, Asiago, Gruyere, grated

- ¼ cup (60 ml) fresh chopped herbs (a mix of parsley and tarragon compliments the mushrooms well.)

Instructions

Note: the babka dough rests overnight in the refrigerator, so begin your preparation at least one day before you want to serve the babka.

- Combine the milk, yeast, and one tablespoon of the sugar in the bowl of a stand mixer, fitted with a dough hook. Let the mixture stand for about 7 minutes until it becomes slightly foamy.

- Whisk together the flour, salt, and remaining sugar, then add it to the yeast mixture with three of the eggs. Knead together on low until the mixture comes together into a shaggy dough, about 5 minutes. Use a spatula to scrape down the sides of the bowl.

- Add the butter, one piece at a time, until it is completely incorporated into the dough, which should now be pliable and have a nice sheen to it.

- Cover the dough with plastic wrap or a slightly damp kitchen towel and let it rise in a warm place for 1½-2 hours until it is doubled in size.

- Turn the dough onto a well-floured surface and punch it down. Then flour your hands and shape the dough into a tight ball. Oil a bowl and place the dough in it. Cover with plastic wrap and proof overnight (8-12 hours) in the refrigerator.

- While the dough is proofing, make the filling.

- Sauté the mushrooms in the butter until they have released all of their liquid, then reabsorbed it. Add the salt as you cook. Let the mushrooms cool in the pan until proceeding to the next step.

- Combine the mushrooms, ricotta, nutmeg, and soy sauce in a food processor, fitted with a steel blade. Process until the mixture is a smooth paste the texture of pesto.

Assemble the Babka

- Prepare a 9-inch loaf tin by buttering it generously and lining it with strips of parchment paper that hang over the edge of the tin at each end. This sling will make it easier to remove the babka from the tin.

- Turn the dough onto a well-floured surface, then roll it into a rectangle with the long side facing you. Roll it out as thinly as you can (.05 centimeters or ⅛ inch is optimal). Use a sharp knife or pizza slicer to trim the shorter ends of the rectangle.

- Spread the mushroom mixture over the surface of the dough, leaving a 1-inch border on all sides. Sprinkle the cheese and chopped herbs over the mushroom filling.

- Beginning with the side closest to you, roll the dough lengthwise into a tight cylinder. (The tighter the cylinder, the more impressive the design of your filling swirl!) Seal the edges by brushing a bit of water on the dough and pinching the ends together.

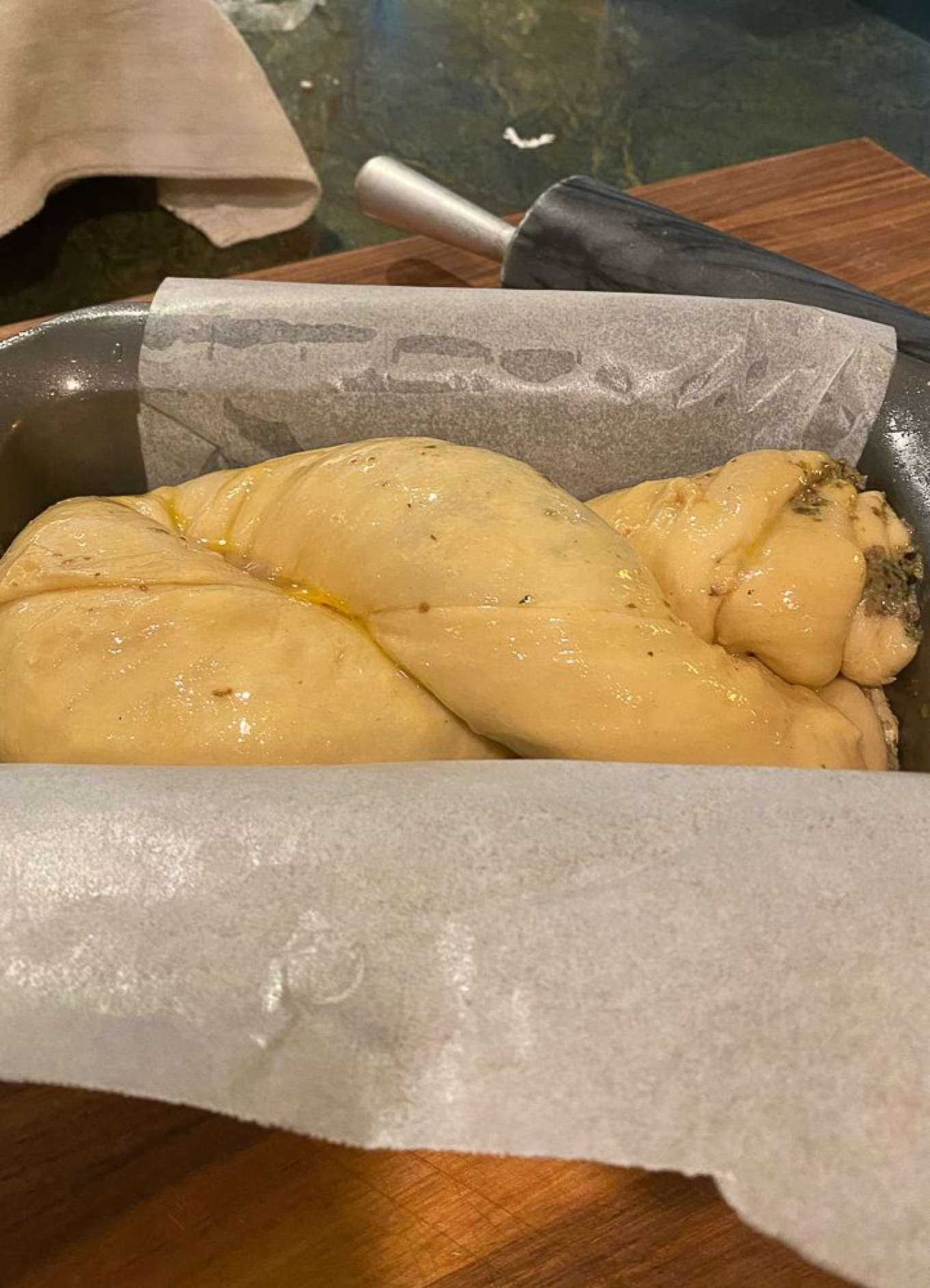

- At this point, you can twist the dough into a simple figure eight, but if you are feeling more daring, use a serrated knife to slice the cylinder into two, then braid the two halves together into a spiral with the cut sides facing up. Place the babka in the prepared loaf tin, cover, and let rise in a warm place for a final 1½ hours.

- Preheat the oven to 375ºF (190ºC). Adjust the oven rack to the middle position.

- Whisk the egg with a tablespoon of water and brush it over the surface of the babka.

- Bake the babka for 45 minutes. To test for doneness, insert a skewer into the babka. If it comes out clean, the babka is ready. If it has bits clinging to it, bake for an additional 5-7 minutes.

- Let the babka cool in the tin for at least 30 minutes. Remove from the tin and serve.

Alternate fillings

Make it Balkan

Combine 1 cup (453 ml) of roasted red peppers with ⅓ cup (80 ml) feta cheese and ⅓ cup (80 ml) ricotta. Add fresh basil and a good squeeze of lemon juice and lots of black pepper.

Make it Baltic

Combine 1 cup (453 ml) blanched spinach, well drained, with ⅓ cup (80 ml) ricotta. Add ⅓ cup (80 ml) goat’s cheese and ½ cup (125 ml) chopped dill.

Make it Mediterranean

Combine ⅔ cup (160 ml) Pesto Genovese with ⅓ cup (80 ml) ricotta and ⅓ cup (80 ml) grated Parmesan.

Recipe for dough adapted from PBS Food

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.