“Two times a month, Tuesday is my favorite day of the week, because when I come home from school, the newspaper Zolotoi Klyuchik (Golden Key) is waiting for me in the mailbox. The sound the paper makes and the way it feels, the smell... Nothing can replace print newspapers and magazines!”

That’s the opinion of a reader — eighth-grader Varvara Tupikova.

Survivors from the past

The Soviet Union produced dozens of children’s magazines, some for only a few years, others for decades. Kolobok, Levsha, Pioner, Yyozh, Druzhniye Rebyata and many others were delivered to schools, libraries and private mailboxes from Kaliningrad to Chukotka. Almost all of them stopped printing years or even decades ago. Some, like Misha, a magazine for primary school children, survived the Soviet breakup by adding foreign language lessons, comics and the basics of a market economy. But all the same, it closed in 2018.

One national magazine that has survived is Yuny Naturalist (Young Naturalist), which celebrated its 92nd anniversary in 2020. But circulation has dropped from 4 million copies in the 1970s to about 10,000 copies today. Competition from television and internet is fierce.

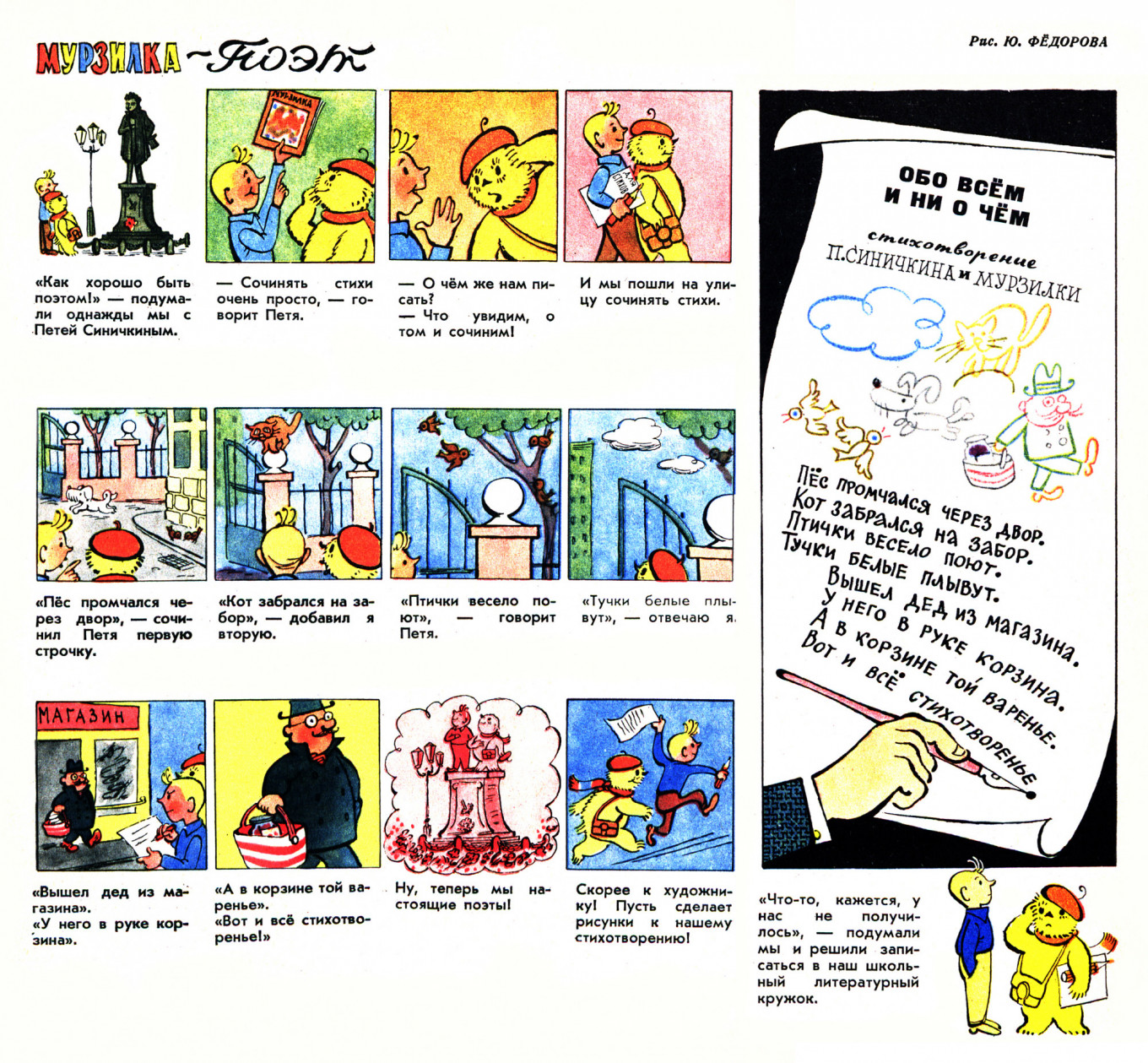

But another magazine has survived even longer. In 2012, Murzilka was listed in the Guinness Book of Records as “the longest-running children's magazine.” This year it celebrated its 96th anniversary.

Murzilka’s editor-in-chief, Tatyana Androsenko, told The Moscow Times what she believes is the secret of their longevity. “Children begin to learn about the world, and Murzilka helps them make sense of it.”

Murzilka has a presence on the main social media platforms in Russia - VKontakte, Facebook, Instagram - and a website for children, parents, nursery teachers. But, Androsenko said, “Staying true to yourself in the internet age isn't difficult… [all you need are] good writing and high-quality illustrations.”

Another secret to their success is an old concept with a modern name: actionable articles. The magazine is filled with educational articles to help children with their school lessons. This is especially valuable in smaller towns and villages where books might be scarce and internet access is not universal.

Local magazines for local kids

For smaller regional children’s magazines, the key to success is to maximize the value children get from print while using digital media for what it can bring— and to stay true to your roots.

In Belgorod, Bolshaya Peremenka (Big Recess) has been published since 2013. Today it has a print edition, website, communities in social media networks — all with different content.

The magazine uses readers to be their writers. For an article about determining the age of a tree, they found a child who had written about it. And they have remained truly local: a Belgorod teacher in the local tourism school wrote about how to prepare for a hike, and a respected local doctor explained why children should be vaccinated.

Zolotoi Klyuchik is another regional newspaper that has been published since 1993. Editor Sofia Milyutinskaya said that they have a synthesis of print and digital. In the Russian platform Vkontakte they publish news, announcements, video, photos, and there is a game section with encrypted words that can be deciphered using QR codes in the magazine.

They also see some of the benefits of print for children’s development. “Children can’t develop fine motor skills on the internet. But they can with the games and crossword puzzles in each issue of Zolotoi Klyuchik,” Milyutinskaya said.

Putting kids in the spotlight

The head of a children’s library in Lipetsk, Varvara Mishacheva, told the Moscow Times that, “Murzilka and Zolotoi Klyuchik are popular because of reader contributions. Children like to see their own works in print, and they like to read about themselves and their friends.” They also like to have a say in the contents. This year they voted for special editions (dragons in spring; hedgehogs in summer).

In Belgorod, every year the editors of Bolshaya Peremenka choose children who have won sports competitions. They write about them and award them diplomas and gifts.

“Children need heroes to look up to, especially heroes who are peers living next-door to them,” Elena Talalayeva, the editor-in-chief of the magazine, said.

And readers want material prepared especially for them. “The advantage of periodicals is that they contain a large amount of useful information, presented briefly and concisely, that is accessible to even the youngest readers. There is a lot of information on the internet, but most of it is too complex,” Irina Kolayeva, head librarian at the Mikhail Prishvin Lipetsk Central City Library told The Moscow Times.

In at least one case, an old children’s magazine is making a comeback. From 1990 to 1995 the magazine Tram published authors not found in other children's magazines. Children could read works by writers Daniil Kharms, Nikolai Zabolotsky, Anna Akhmatova, and Vladimir Nabokov, and read articles about painters like Kazimir Malevich and Marc Chagall. Popular science articles were written as fiction. The magazine had a fanatic following of what editor Tim Sobakin called “clever children.”

The magazine ceased publication due to funding problems, but there is now a large community of its fans on Russia’s social media networks. In 2011, the magazine was reprinted and now has a site, where librarians and booksellers plead for hard copies.

Varvara Tupikova is right: there is nothing like a print edition.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.