When Joe Biden said in 2011 that he had looked into [Putin’s] eyes and found that he had no soul, Vladimir Putin’s response was: “We understand one another.” With Biden elected the forty-sixth president of the United States, and Putin allowed under the recent constitutional amendments to stay in the Kremlin through 2036, this promises to be one of the coldest personal relationships between the U.S. and Russian leaders.

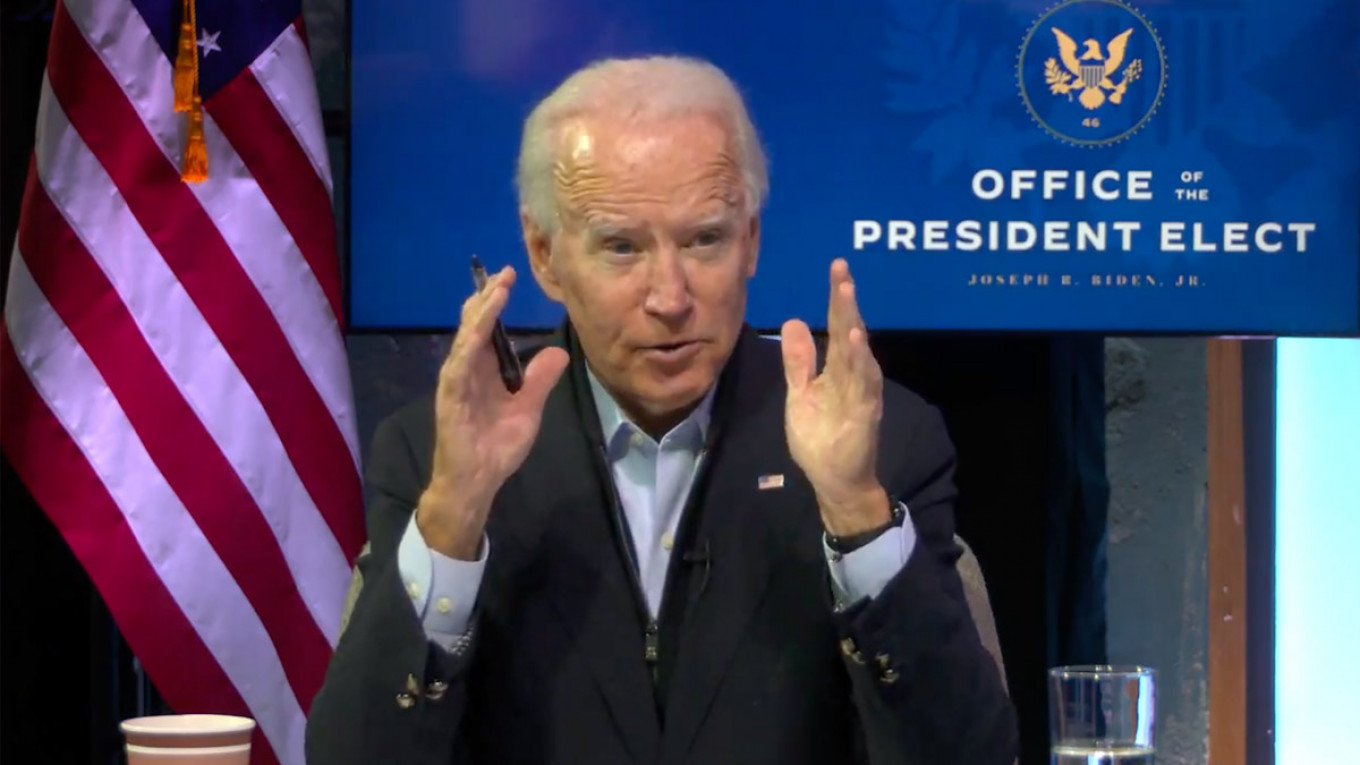

In terms of foreign policy, President-elect Biden is often compared in Russia to his former boss Barack Obama, but although many of the people likely to get top positions at the National Security Council, the state and defense departments, and the U.S. mission to the UN are former members of the Obama administration, Biden’s foreign policy experience goes back much further.

For the seventy-eight-year-old, the Cold War is not something he learned about from books, like Obama, but something he lived through. Elected to the U.S. Senate in 1972, Biden visited Moscow in 1979, when the ill-starred SALT-2 treaty was signed, and then again nearly a decade later just after the signing of the INF agreement, which was canceled by Donald Trump last year.

A photo taken during the latter trip of Biden with Andrei Gromyko, the patriarch of Soviet diplomacy who was then the nominal head of state of the USSR, has become a big hit on Russian social media since Nov. 3. Therein lies a major distinction between Biden and Obama where it comes to Russia: for Biden, the present confrontation with Moscow is a postscript to the Cold War. And like the Cold War itself, it must be won by the United States.

Of course, Biden does not entirely conflate Russia with the Soviet Union. As a U.S. senator, a longtime chairman of the Senate Foreign Relations Committee, and a two-term U.S. vice president, he has been intimately involved in world affairs for almost a half century.

However, while Biden recognizes China as America’s top competitor, he calls Russia the biggest threat to the United States. Even though he describes Russia as a country in enormous decline, an oil-based economy and a second-rate military power, unable to compete with the West and saddled with depressive demographics and a kleptocratic regime run by KGB thugs, he sees Moscow’s policies as aimed at weakening Western countries internally; undermining the unity of such institutions as NATO and the European Union; and subverting the liberal world order. He sees an increasingly revanchist, aggressive Russia that is taking the fight beyond the former Soviet space and getting closer to China.

Yet Biden does not believe that the attempt made at the end of the Cold War to integrate Russia into the U.S.-dominated system was a mistake. He rejects any notion that the failure of that effort was the result of NATO’s eastern enlargement: Russian paranoia, in his view, should not be condoned. Rather, the problem was the takeover of the Russian state by its security services.

However, Biden is not giving up on Russia. There may not have been any Arab Spring-style ouster of Putin in 2011–2012, but Biden hopes that new opportunities will present themselves in the future.

Thus, in Biden’s view, Russia should not be cornered: one, it would make it too dangerous for the United States; two, the only thing that keeps Putin in power is nationalism and anti-Americanism. Eventually, Russia will come back to its senses, ditch Putin’s policies, and recognize that it cannot rebuild itself unless it engages with the West.

Such a conclusion provides an insight into Biden’s future policy toward Russia and suggests that that policy will be to better coordinate the Russia-related activities of U.S government agencies; mount a cyber offensive against Russia; consolidate U.S. alliances and partnerships; put pressure on Russia and make it pay a very heavy price for its misdeeds; but also structure the conflict not as one between the United States and Russia, but as between the Russian kleptocracy and oligarchy on the one hand, and the Russian people on the other, with America supporting Russia’s “underground civil society.”

Exposing Russian official corruption through leaks, while naming and shaming the perpetrators and discrediting the Kremlin in the eyes of ordinary Russians is the main tool of this approach.

Besides extending the frontline of the U.S.-Russian confrontation to include democracy and human rights, Biden can also be counted on to take on Russia more boldly in the former Soviet Union, from Ukraine, Belarus, and Moldova to the South Caucasus and Central Asia. For years, he closely oversaw Washington’s Ukraine policy for Obama; more recently he has been very vocal in support of the Belarusian opposition and highly critical of Moscow’s policies toward Minsk, as well as Russia’s role in Nagorno-Karabakh. More U.S.-Russian friction in all those regions is a sure bet.

Biden’s win promises a more coordinated Russia policy within the NATO alliance. Over the last few months, the stance of European countries on Russia has significantly hardened, bringing Europe very close to America’s position. Germany, once Russia’s advocate in the West, has turned into the leading critic of Kremlin policies within the EU and the initiator of sanctions campaigns against Russia.

Out of willingness to heal the rift between Washington and Berlin caused by Trump’s disruptive behavior, Biden might let the Germans decide for themselves the fate of the Nord Stream 2 gas pipeline from Russia. However, his own concerns about Europe’s energy dependence on Russia, plus the growing opposition in the U.S. Congress to any Russian energy projects in Europe might make him continue Trump’s pressure on Germany to cancel Nord Stream 2.

Another follow-up from the forty-fifth president could be the development and ultimately deployment in Europe of U.S. intermediate-range missile systems that would target Russian command centers and strategic assets at very close range. Biden supports arms control, including the extension of the New START Treaty negotiated by the Obama Administration, but he favors arms negotiations from strength.

Looking ahead, the prospect of U.S. INF deployments minutes away from Moscow could be one element of that position. Strategic stability talks with Russia, if they begin on Biden’s watch, will be as tough as any in history.

Closing ranks with Europe could be accompanied in Biden’s foreign policy by a mini-détente with China for which Beijing is also keen. Both developments would step up the geopolitical pressure on Russia, which would see its foreign policy options shrink even further. For the Biden White House, everything will be part of a strategy. Russia will not be central to it, but neither will it be absent. The ultimate goal appears to be to undermine Putin’s nationalism, destroy Russia’s near-alliance with China, and return the country to the position of an adjunct to the West.

Rather than how he is portrayed in the Russian media — in short, as an infirm figurehead — Joe Biden is a seasoned foreign policy professional, a strategic thinker, and a ruthless player.

He will be flanked and assisted by a group of ambitious, sophisticated, and energetic aides eager to leave their mark on American foreign policy—and the world. Biden’s term will overlap with the rest of Putin’s current one. It will be during that time that Putin has to make his fateful decision about the 2024 elections, and a lot will happen between now and then.

It is good that the master of the Kremlin understands whom he will be facing in the White House.

This article was first published by the Carnegie Moscow Center.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.