Alexander, a German citizen, first met Anna on Valentine's Day during a break from his studies in Russia's grand imperial capital St. Petersburg.

She had offered to show him around her home city during his two-week course after they connected on the Couchsurfing platform. As they ate dinner at a Soviet-style restaurant with rugs decorating the walls and went ice skating on an outdoor rink, they talked about their different cultures and dreams for the future — and found themselves falling in love.

“It was all very romantic and beautiful and I knew from the beginning that she was very special to me,” Alexander said. “She later told me she had the same feeling about me.”

But soon after Alexander returned to Germany, the coronavirus pandemic halted almost all international travel, throwing their future together into uncertainty.

“We were very optimistic and thought the situation would change soon. I think we only realized in May how serious it was,” Anna said.

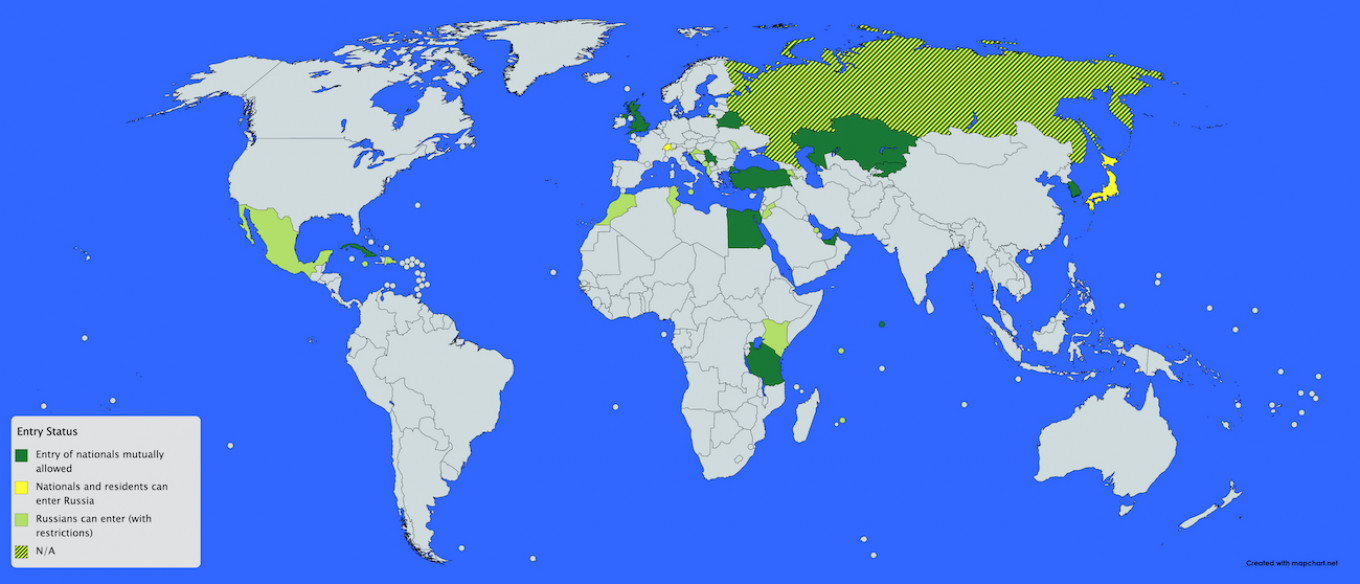

While 12 European countries and Canada have allowed entry for binational couples who can show proof that they are in long-term relationships, Russia remains closed to non-married foreign partners. Many of them call the country’s entry rules opaque, confusing and restrictive. With no end to the pandemic in sight, these couples are calling on Russia to allow them to reunite.

In addition to calling and emailing the Russian authorities, they have organized an online petition — affiliated with the global Love Is Not Tourism movement — urging the government to open the borders for binational couples and families. So far it has gathered more than 16,500 signatures.

“We already see the detrimental mental health impacts of the pandemic: growing depression rates, new phobias, newly acquired obsessive-compulsive and anxiety disorders,” said Yana Kataeva, a family counselor and founder of the Grown Up Relationship School. “While I have not come across studies about couples deprived of opportunities to see each other, I believe them to be at a higher risk than couples living together,” she added.

Complications for couples split between Russia and other countries are compounded by the various types of visas available.

Since July, foreigners holding highly-qualified specialist visas have been allowed to enter Russia, but their non-Russian spouses and family members have not, said Timur Beslangurov from the Moscow-based Vista Immigration agency.

For Seth Bernstein, the situation has been especially difficult. A U.S. citizen who was based in Russia with his Russian wife and young son before moving to Florida for work in January, he has been unable to visit his family in Russia because he holds a scientific-technical visa, not a family visa.

Meanwhile, his wife’s final U.S. green card interview was indefinitely postponed due to the U.S. Embassy in Moscow’s suspension of non-emergency visa operations. Bernstein’s appeals to the embassy and to his elected representatives have been fruitless.

So far, the simplest workaround for these couples and families has been to meet in a third country that is open to foreign tourists, such as Turkey. Bernstein was able to meet his family there, as were Alexander and Anna.

Otherwise, text messaging and video calls are the only substitute for in-person contact for the foreseeable future.

“The funniest thing is that ... when my son saw me in Turkey after six months of video chatting every day, he didn’t recognize me,” Bernstein said. “He was quite scared of me for about 15 or 20 minutes. Not scared, just very shy. Part of it was that he’d been on an overnight plane, but it was still kind of disconcerting.”

It’s unlikely that Russia will open for non-married couples before it reopens its borders to all countries, said Beslangurov.

“Russia is a very formal country. Russia needs to see the documents. Otherwise, pretty much everyone would say they’re in a relationship [with a Russian] to enter,” he said, pointing to instances in which people have falsely claimed they were seeking medical treatment in Russia to get through the closed border.

For the most up-to-date information on coronavirus-related travel restrictions for Russia, Beslangurov recommends consulting the International Air Transport Association’s travel regulations map and the Russian federal border service’s coronavirus information page.

“I doubt that the Russian authorities will open the borders to all countries right now; it's not possible because of the Covid situation,” he said. “I believe that we'll continue to see borders opening to particular countries, like we’re seeing with Japan, Serbia [and Cuba] now. They claim that they will not close the borders for everyone again like before, but who knows.”

The Russian Foreign Ministry did not respond to The Moscow Times’ request for comment on whether entry requirements will be changed to accommodate binational couples.

Muscovite Elizaveta Pereguda and her husband, a Saudi national based in the U.S., were separated by a bureaucratic wall for months. Pereguda had relocated to Moscow at the start of the pandemic to settle an issue with her U.S. visa — but the quick stopover turned into a months-long stay due to the U.S. Embassy’s suspension of work.

“Since we were prepared to be apart for a couple of months, the mounting uncertainty as time passed was the hardest. There was no expiration date on this separation,” Pereguda said.

The couple also tried to make use of the rule allowing Russians to request visa invitations for spouses and close family members, but her husband was denied a Russian visa due to a spelling error. Pereguda called the process “the worst experience of my life.”

Pereguda eventually obtained her U.S. visa several weeks later and flew there via Turkey, though the couple already had a backup plan of temporarily moving to Mexico just to be together.

“We did not plan to get married so soon after the engagement, but are now so glad we did since it gave us more options for a reunion,” Pereguda said. “I have heard of much worse situations ... Honestly, we just got lucky.”

For Alexander and Anna, the distance has posed an unexpected test for their fledgling relationship. While Germany allows foreigners to apply to enter the country if they are in a relationship, it’s not guaranteed that Anna will qualify when she tries to visit Alexander there in December.

“It’s very frustrating to be apart not knowing when we will see each other again, not being able to plan the near future together,” Anna said.

For now, they’re just doing what they can to keep their romance alive from miles away like thousands of other couples around the world.

“I even wrote her a poem that I will come to Russia someday to be with her again like the sailor from the Scarlet Sails story... and I never write poems,” Alexander said.

Some last names have been withheld for privacy.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.