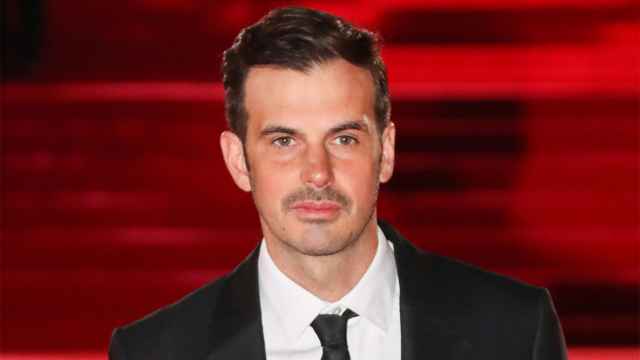

Filmmaker Roma Liberov, renowned for his whimsical and moving literary-cinematic works, is releasing a new film on November 5. “The Innermost Man” is inspired by the life and prose of Andrei Platonov, one of Russia’s most paradoxical writers. It is a captivating new addition to Liberov's series about 20th century Russian writers, who each found a way to survive harsh Soviet realities and preserve their talent and integrity amid censorship, pressure or threats.

The film’s title is a reference to Platonov’s 1928 novel of the same name. The filmmaker takes “the innermost man” as a personification of a genuine, sincere person, true to themselves, someone, whose precious inner world survives any challenges, turbulence or torment that the outside world may throw at them.

“A collective image of a survival strategy”

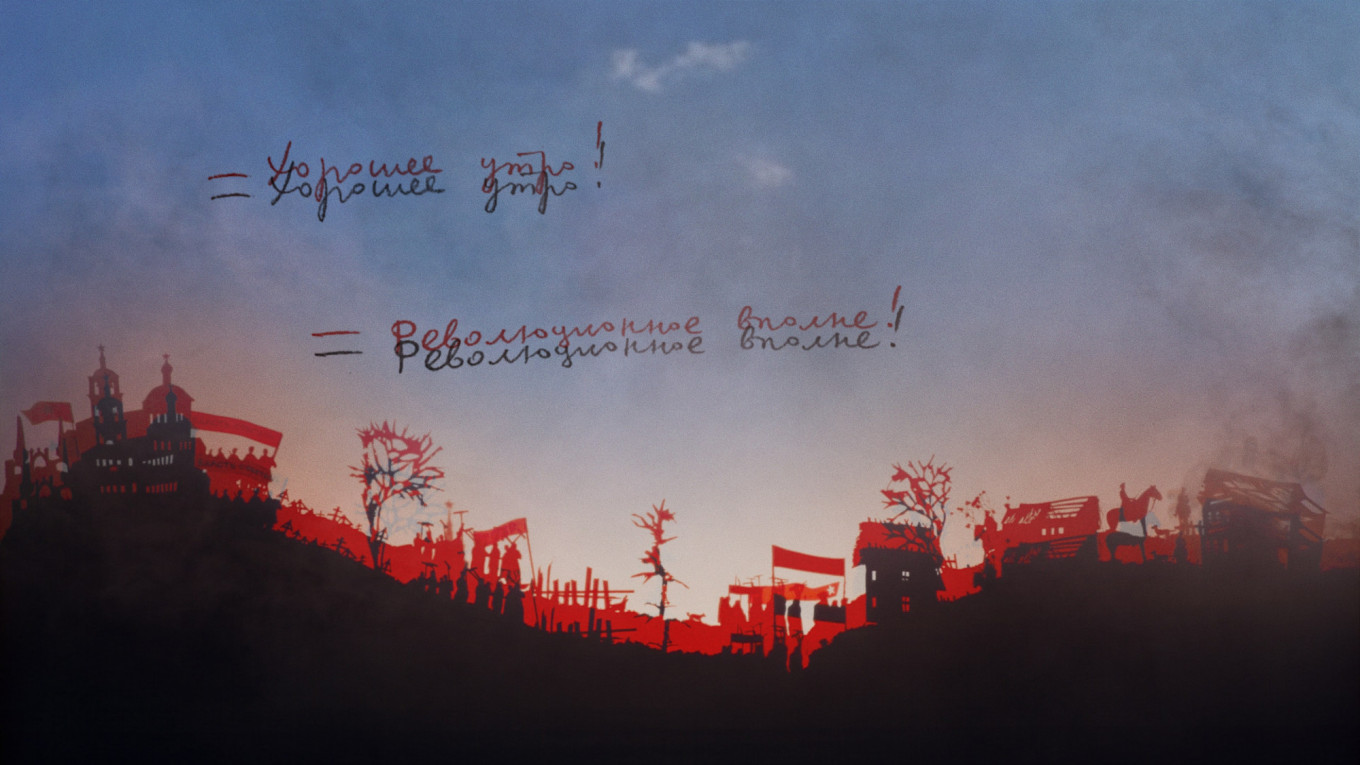

In “The Innermost Man” Liberov fuses the elements of Platonov’s biography with the seven days of creation. The film tells a tragic story of the birth and collapse of the new world, where a larger-than-life communist dream falls to pieces under the press of reality.

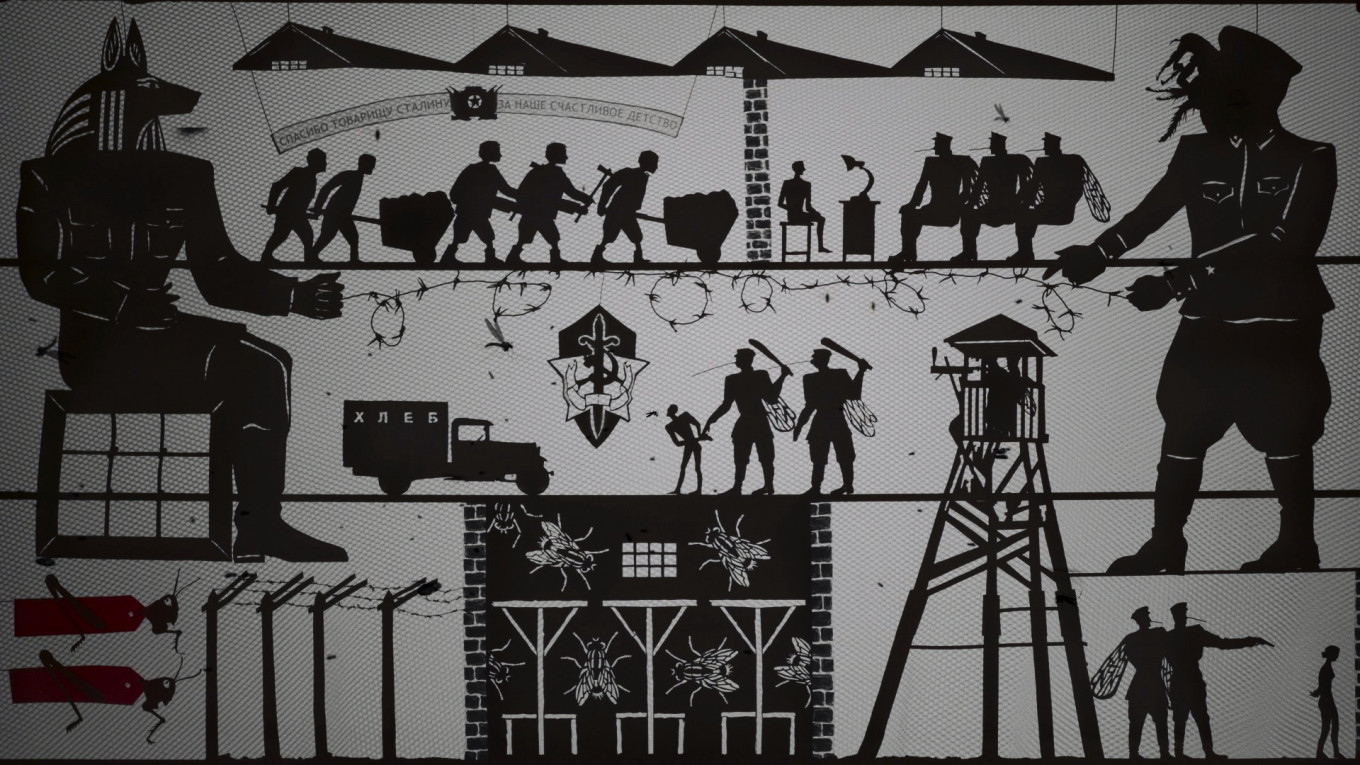

Starring Andrei Bely, Timofei Tribuntsev and actors from Moscow’s Dmitry Brusnikin Studio as well as amateur performers, the film brings together elements of animation based on Platonov’s drawings, shadow theater episodes by the St. Petersburg’s Kukfo puppet theater, existential hymns from Grazhdanskaya Oborona rock band and documentary landscape shootings made near Voronezh, where Andrei Platonov was born. Liberov has also included visual references to ancient Egypt, drawing parallels to both the titanic construction projects and the absolute power of the state.

“The Innermost Man” follows in the footsteps of Liberov’s earlier works on Soviet writers, including Yuri Olesha, Joseph Brodsky, Sergei Dovlatov, Ilf and Petrov, and Osip Mandelshtam.

“For me, the language of the writer always comes first,” Liberov told The Moscow Times. “You may have noticed that Platonov’s characters talk in a very particular way, as if they spoke straight from the gut. This language feels a bit awkward, but it is full of character and very sincere,” Liberov said.

“For this reason, in my film you won’t see the characters talk to each other onscreen — they will be acting, but we will use voiceover to tell the story.”

Liberov's fascination with literature dates back to his youth. When he was a student at a film institute, he went on a quest to discover a visual language that would resonate with the language of a particular writer. Today, Liberov has made it his signature style, bringing animation, graphic design, photography, music, documentary, and puppet theater into his whimsical and touching takes on the lives of 20th century Russian writers.

“I am most interested in the survival model of a member of Russian intelligentsia in a totalitarian state,” Liberov said. “Every writer featured in my films has his own model. Each writer had his own unique language and the ability to use this language to express themselves in a clear, transparent, unequivocal way. Seen as a series, the writers’ life stories contribute to a collective image of a survival strategy of a particular breed of people.”

Platonov on paper in Russian and English

Robert Chandler, an award-winning British poet and translator, whose works include a number of translations of Platonov works, is convinced Platonov is important today for Russians and foreigners alike.

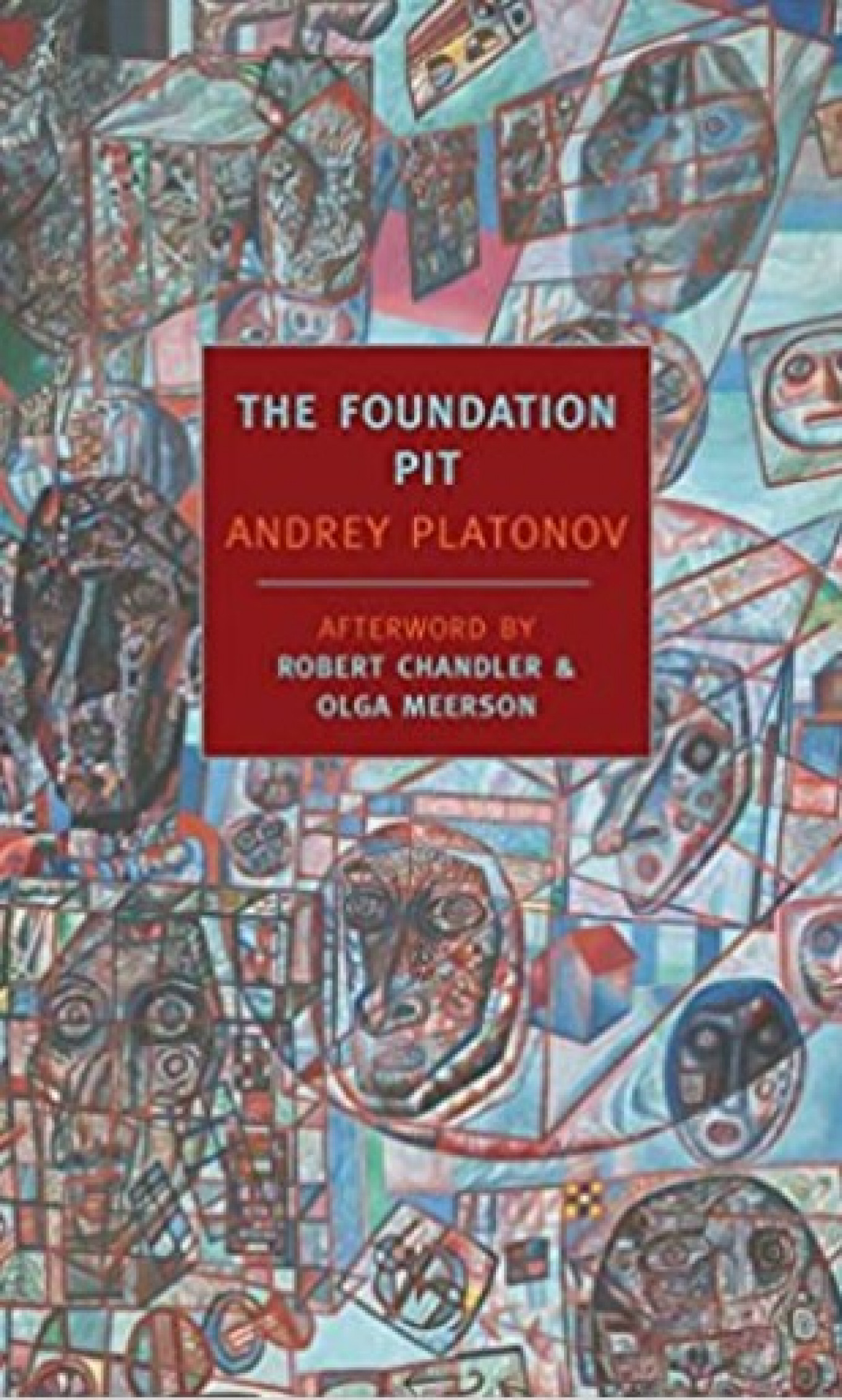

Chandler first read Platonov during the year he spent as a British Council exchange student in Voronezh, in the early 1970s. A friend lent him her copy of one of the somewhat censored Soviet editions of his work. “I wouldn’t say that I at once fell in love with his writing, but I recognized its uniqueness,” he told The Moscow Times. “Back in England the following year, I read Western-published editions of his more political works – “The Foundation Pit” and his one long novel, “Chevengur.” I was entranced by the sharpness and black humor of the more satirical passages and began trying to translate him then and there. It took me many more years fully to appreciate the tenderness, subtlety and wisdom of his later works.”

“Platonov uses the Russian language as creatively as Mandelstam, Tsvetaeva or any of the greatest poets of the last century,” Chandler continued. “His language is idiosyncratic yet also strangely impersonal; I have heard it described as ‘the language that might be spoken by the roots of trees.’ Perhaps surprisingly, this does not make him impossible to translate. His psychological understanding, the vividness of his perceptions and the wisdom of his later works are all entirely translatable.

“Platonov was equally remarkable for the courage and endurance with which he survived any number of personal and social tragedies It is unlikely that he intended it as such, but the following paragraph about a plane tree, written in 1934, now seems to be a description of Platonov himself: ‘Zarrin-Tadzh sat on one of the plane tree’s roots ( . . . ) and noticed that stones were growing high on the trunk. During its spring floods the river must have flung mountain stones at the very heart of the plane, but the tree had consumed these vast stones into its body, encircled them with patient bark, made them something it could live with, endured them into its own self, and gone on growing further, meekly lifting up as it grew taller what should have destroyed it.’”

Platonov on film

Alexander Mamontow, film producer, director and actor, the founder of the International Festival of Festivals film festival, who currently lives in Berlin, finds Liberov’s works painfully relevant today.

Mamontow is reminded of the notorious 1922 Philosopher’s Steamboat that was arranged by Lenin to evict dissident intellectuals and academics from Soviet Russia.

“The boat sent a clear message. They didn’t just expel the people. They expelled critical thinking and the dissident movement as such, and those who remained in the country faced a hard, often tragic fate and painful moral dilemmas,” Mamontow told The Moscow Times. “Andrei Platonov’s 1930 novel, ‘The Foundation Pit,’ arguably one of the most tragic pieces in the history of Soviet literature, masterfully recreates the eerie and absurd feeling of a society where dissidents are expelled, repressed and physically destroyed.

“In his new film, Liberov has found the most compelling visual language to make us feel both the Platonov’s prose and the Soviet realities that prompted this prose to emerge. This is a language that reflects and transmits the feelings of illiterate people, the peasants, who were facing a new reality, a world where mass repressions and the annihilation of dissident human beings not only becomes commonplace but is even presented as a necessary means of achieving a bright better future for those who survived the purges,” he said. "And while no boats are being sent today, the Russian dissidents are not welcome at home, once again.”

The film will debut in Russia on Nov. 5 and after a run in theaters be available online. You can rent Liberov’s previous films (in Russian; no subtitles) on a variety of platforms. See this site for more information and links to online platforms.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.