The Engineering Building of the Tretyakov Gallery is hosting an exhibition that is a must-see for anyone interested in early 20th-century Soviet art. It is a show of works by Sarra Lebedeva, one of the 'Amazons of the Avant-Garde' that included the better known Vera Mukhina, Anna Golubkina, and Yekaterina Belashova.

The exhibition is the most representative and complete show of Sarra Lebedeva’s work since her first major exhibit at the same museum in 1969, two years after her death.

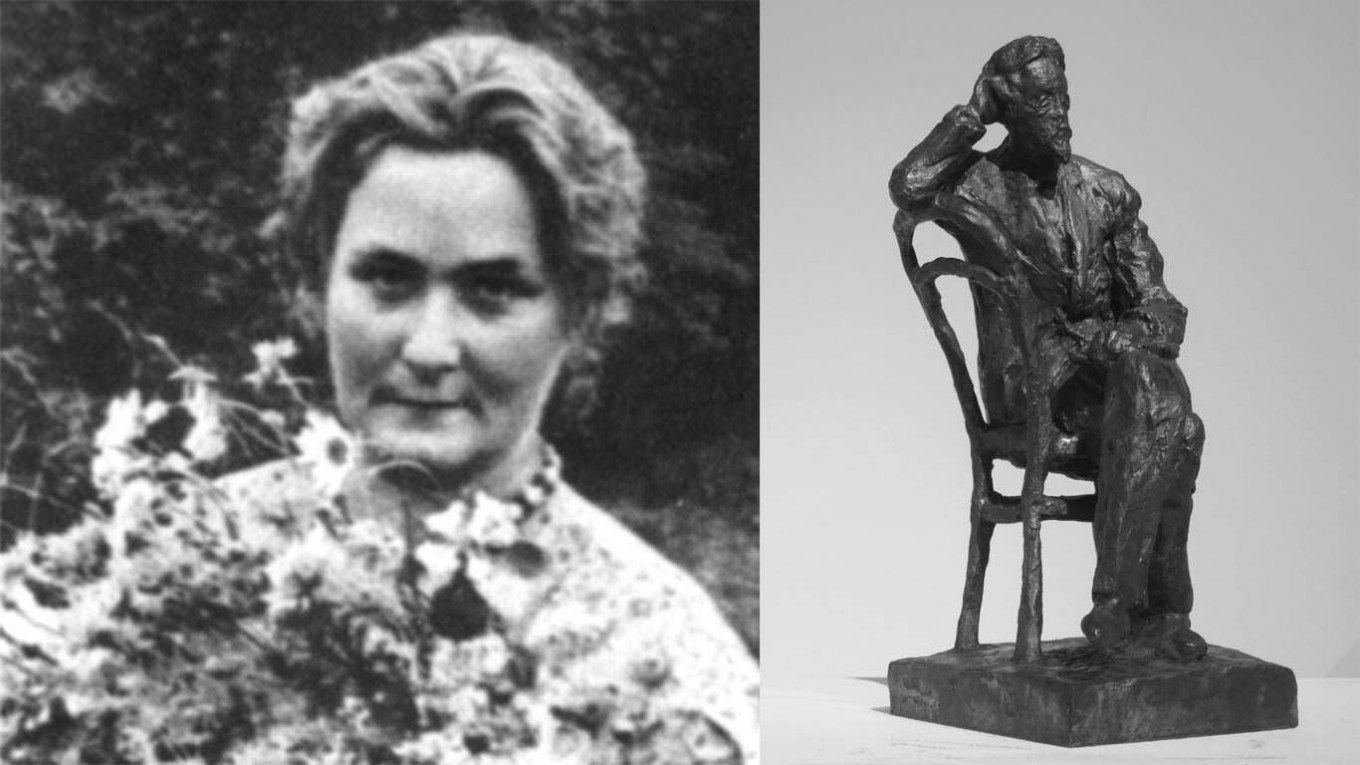

Notes from an illustrious biography

Sarra Lebedeva was born in 1892 in St. Petersburg, the fourth daughter in the big family of a banker, Dmitry Darmolatov. Family legend has it that her parents gave her the Old Testament name of ‘Sarra’ as a sign of protest against the state policy of anti-Semitism in the Russian Empire at the time.

In her youth Lebedeva traveled a great deal around Europe, where she fell under the spell of French Impressionism in sculpture, particularly Aristide Maillol, a follower of Rodin.

In 1914 she married the graphic artist Vladimir Lebedev and took his surname, which she kept even after they divorced in 1925. An illustrator of children’s books who was also known for his elegant watercolor nudes, Lebedev had a great influence on his wife’s work, which can be seen in the graphics on display in the second hall. Lebedeva, known for her hospitality, welcomed into her home some of the best and brightest of the time, including writer Ilya Ehrenbug, and the artists Sergei Gerasimov and Vladimir Favorsky.

After the Revolution, Lebedeva was very involved in Lenin’s plan for monumental propaganda art. Much of her work from the 1920s wasn’t preserved, but there is a bas relief portrait of Robespierre, one of the leaders of the French revolution.

Lebedeva’s most successful years were the 1930s. She did memorable portraits of the aviator Valery Chkalov and the “shock worker” Alexei Stakhanov, the latter portrayed with a kind of sadness in his eyes that was not typical of Soviet heroes. However, that was an exception. Most of her work was more representative of the age, such as a metro worker with a jack hammer or the fine portrait of Vanya Bruni done in 1934 and usually displayed in the New Tretyakov Gallery.

A walk back in time

Lebedeva is much less known to the broad public than Vera Mukhina — author of the iconic sculpture of “Worker and Collective Farm Woman” — who was wise in the ways of relations with the authorities and even conducted a correspondence with Josef Stalin about doing his portrait. The exhibition displays Lebedeva’s splendid portrait of Mukhina along with sculptures of her friends: the actor Solomon Mikhoels, the poet Alexander Tvardovsky, and the writer Mikhail Prishvin.

As noted in the introduction to the exhibition, “Lebedeva understood the task of sculpting a portrait as creating a documentary image from life. ‘Documentary’ meant being faithful to nature, that is, conveying both the physical appearance and the unique intellectual-emotional personality of her subject. She had nothing in common with Golubkina’s subjectivism or Mukhkina’s pathos, approaches which led to the model being transformed by the will of the sculptor.”

One of the highlights of the show is the particularly expressive seated figure of the artist Vladimir Tatlin, author of the famous "Monument to the Third International" (a model of which stands in the New Tretyakov Gallery) who was mercilessly persecuted for formalism at the apex of Stalin’s campaign for socialist realism. Another fine piece is the sculpture of the artist Nadezhda Udalstova, widow of artist Alexander Drevin, executed by the NKVD during their campaign to rout out Polish and Latvian “traitors” in 1938. Lebedeva creates a psychologically insightful image of this great artist of the Russian avant-garde as a woman who has been tormented but not broken. The portrait is placed between a bronze image of the brilliant star of the Moscow Art Theater and widow of Anton Chekhov, Olga Knipper-Chekhov, and a portrait of poet and writer Boris Pasternak done as a bas relief for his grave in Peredelkino.

Lebedeva’s most famous work is a statue called “A Girl with a Butterfly” (1935-36), which has been reproduced countless times on book covers about Soviet life, exhibited in Gorky Park and even recreated in cement. In the words of the renowned historian of sculpture Boris Ternovets, who knew Lebedeva well, and confirmed by sculptor Ilya Slonim, “A Girl with a Butterfly” was the artist’s favorite work, but it was only cast in bronze in 1968, a year after her death. Critics have noted that Lebedeva succeeded in conveying how fragile and fleeting human life was in her sculptures, and in this sense “A Girl with a Butterfly” is one of the finest and most vivid examples of that characteristic of her work.

Lebedeva was unlucky with state commissions: she never succeeded in doing her monument to secret police founder Felix Dzerzhinsky. That went to Yevgeny Vuchetich, who did the monument that once stood in the center of Lubyanka Square. But the exhibition has an extraordinarily vivid bust of “Iron Felix” placed here under glass and lit with red lamps. On the other side of the hall, also under glass, is a model of her full-length figure of Dzerzhinsky.

Final years

In 1959 Lebedeva began work on a monument to Ivan Tevosyan, Stalin’s legendary commissar for the iron and steel industry, that was meant for the city of Elektrostal. But the project was not accepted because Lebedeva refused to make the changes demanded by the state commission for portraiture.

Real Soviet acclaim largely bypassed Lebedeva. She was elected a corresponding member of the Academy of Arts only in 1958 when Stalin’s commissars finally loosened their grip on the visual arts.

After her election to the Academy, she began to work less due to problems with her vision. As she explained to sculptor Ilya Slonim: “I can’t stand not getting it perfect…”

The exhibition is in the Engineering Building of the Tretyakov Gallery until Nov. 22. For more information about the exhibition and tickets, see the museum site.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.