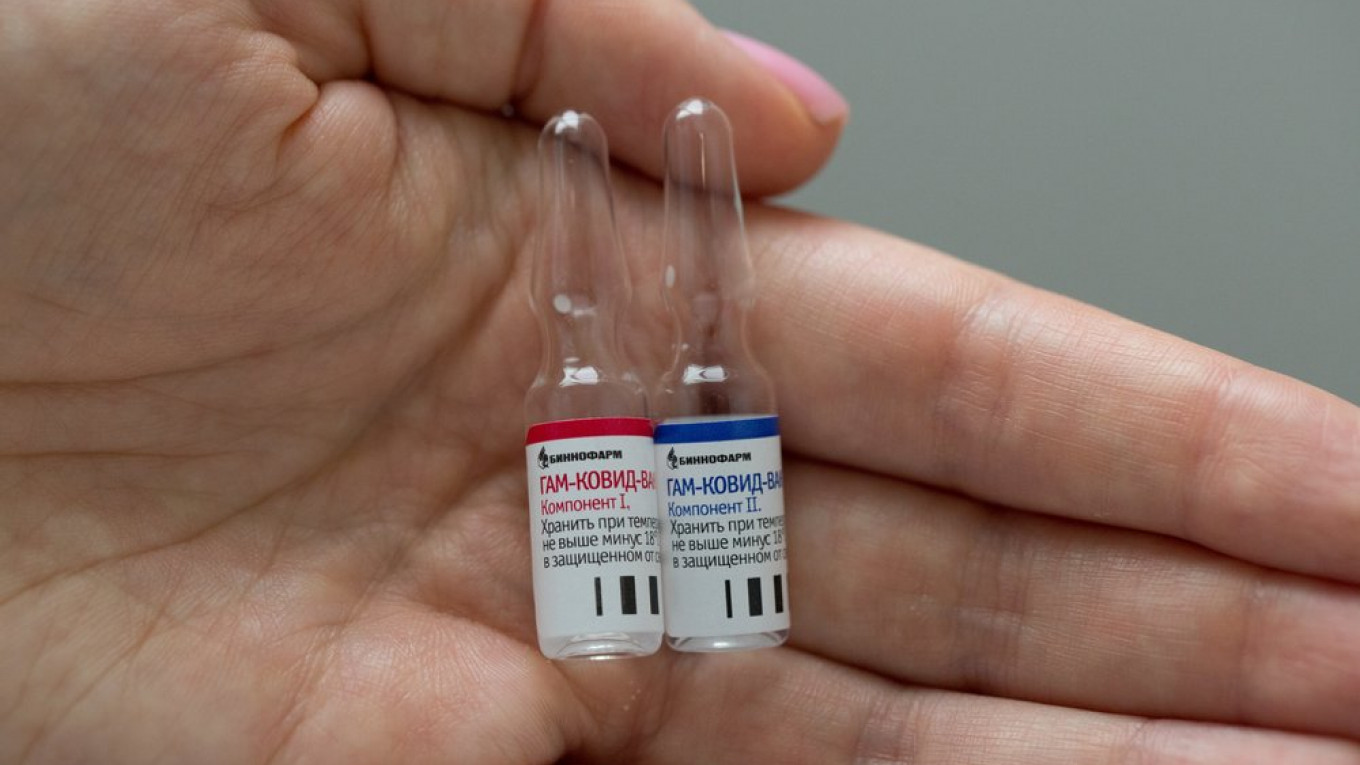

This isn’t Russia’s new Sputnik moment. The approval of a supposed vaccine for the coronavirus by Russia harkens back to something less savory in the country’s history, when research was subservient to politics, and strongmen got the science they wanted to hear, no matter the costs to the Russian people.

President Vladimir Putin’s announcement of a successful vaccine against the coronavirus has been met with universal derision by the scientific community around the world. Why? Not because of jealousy or any anti-Russian sentiment. The new candidate vaccine was simply not tested properly.

Most vaccines and new drugs fail in clinical trials and we do these studies to test our assumptions, keep from fooling ourselves, from hurting those who will take these products. The basic pathway of vaccine and drug approval worldwide is based on three phases of study.

In Phase 1, with a small number of people, researchers test a product for serious and common side effects. In Phase 2, scientists are looking for activity; for a vaccine, if it elicits an immune response (which doesn’t mean the vaccine is protective, it just gets the immune system’s attention), for a drug if it is able to kill the pathogen against which the drug is targeted. But Phase 3 is the pinnacle of biomedical research. Here we see if a drug is safe in large numbers of people where important but less common side effects will appear by virtue of the fact that we are testing in a much larger group than in Phase 1.

If a side effect shows up in 1 in 250 people, we’d be unlikely to see it in a 20-person Phase 1 study, but we’d surely see it in a group of 10,000 people given the product. But Phase 3 is where we also see if a product truly works. In Phase 3, we give half the people the new agent and half the people a placebo or dummy product — the idea is that if your vaccine works, you should see far greater numbers of infections in the placebo group than the one given the vaccine.

For vaccine studies for the coronavirus, getting these Phase 3 studies up and running, accruing enough infections, will probably take at least a year from start to finish. Most of the real data on coronavirus vaccines we’ll see sometime in 2021.

Putin’s vaccine has been rushed to approval after Phase 2. What could possibly go wrong? The history of medical research is littered with examples where early data did not pan out, and in fact, the early promise of a new product turned out to hide dangers only apparent in Phase 3 studies.

Some examples? The Cardiac Arrhythmia Suppression Trial (CAST) study, published in 1991, showed that flecainide, a drug being studied to treat irregular heartbeat in the context of cardiac arrest ended up killing more patients than those on placebo, though the drug worked well for treating irregular heartbeats outside of the context of acute myocardial infarction.

Early studies of vaccines against respiratory syncytial virus in children in the 1960s ended up spurring more severe disease in children than in those receiving a placebo once these infants were exposed to the virus itself through community spread of the infection. Two of the inoculated children died. Modern drug approval is based on careful study to avoid these disasters and we ignore these rules at our collective peril.

One thing that separates vaccines from drugs used to treat diseases is that we have to convince upwards of 70-80% of a community to take them even though they are feeling well and may not see the need to take a jab in the arm.

Cutting corners on vaccine development, risking serious side effects or the chance that the product may actually be a dud, undercuts public confidence in vaccination not just for Covid-19 but for the diseases that we have worked to eradicate for years. If our political leaders are willing to take chances with our lives for one vaccine, why should we trust them with others?

Like our own American President, Putin has put his own interests and politics over his people in the context of this pandemic. Russia and the world need a coronavirus vaccine, but not one rushed to market to meet the whims of one powerful man.

One only has to look back a little further in Russian history, before Sputnik, to see where the big men of the past looking for easy answers went horribly wrong. I am talking about Trofim Lysenko, who said he could grow orange trees in Siberia and was put in charge of Soviet agricultural policies by Joseph Stalin. To the millions killed deliberately in the Holodomor — Stalin’s man-made famine in Ukraine — Lysenko added millions more who perished when the imposition of his policies led to widespread crop failure.

When bad science meets politicians looking for easy answers, you can get a whole lot of trouble.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.