Last summer journalist Marina Dmukhovskaya and photographer Georg Wallner took a trip on the Trans-Siberian from Moscow to Vladivostok. For 28 days and almost 10,000 kilometers, they talked to dozens of people in “Seat 47” (Mesto 47) riding next to them. When they returned, they turned 38 conversations into first-person stories.

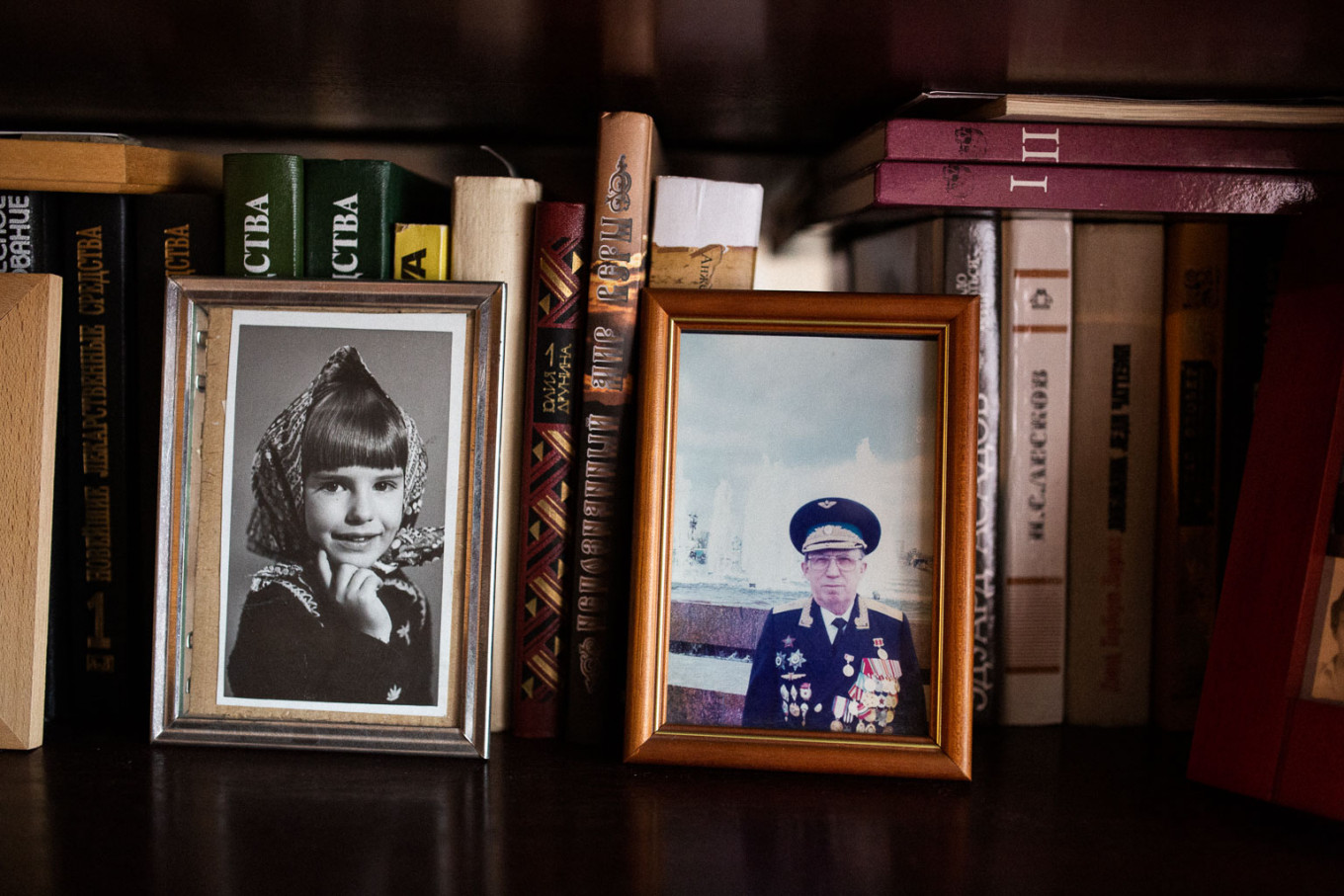

My husband was a military pilot. He had a hard life, and since I was sharing my life with him, mine turned out to be a complicated one too. We lived together for 45 years. We lived in Georgia, Azerbaijan, Russia and Uzbekistan.

He dreamed of becoming a pilot since he was a child. Back then, when Chkalov successfully completed a non-stop flight from Moscow to Vancouver in 1937, all boys wanted to become pilots, and he also applied for a flying school in Kharkiv.

We met when I was 17 years old. He was on vacation from his military service in our village in Ukraine. He stood out: a pilot, all dressed up like a rooster in a parade uniform with a dirk, forage cap…

His brother Boris asked me out for a dance party. We danced just one song, when my future husband approached us and said, “Boris, go rest a bit, I will dance with your girlfriend.” We danced the whole night, and he walked me home. It was May 9, and on the 24th we already registered our marriage. I can hardly remember that day, it’s almost like everything was in a thick fog.

First they didn’t want to accept our application for marriage, because I was not 18 yet. They said that my mom should come, but my husband insisted and pulled some strings, and they let us get married.

I didn’t know anything about family life, I was completely ignorant about sex. There was indeed no sex in the U.S.S.R. Everything was so hidden, that kids didn’t know anything. When I was getting married, I thought that you have sex just once to make a baby. Sometimes girls in the village would say “There are three kids in your family. Wow, you parents have done it three times!”

We could only understand how things worked by watching animals in the village. If a cow had something with a bull, children saw a calf being born. That’s why I thought that we would wait for some years and just live like a brother and sister.

When we went to bed, he tried to approach me. It was a nightmare, he was afraid that I would start screaming on top of my voice. He also had no sexual experience. Two nights we slept together, and nothing happened, and then his vacation was over and he left for Azerbaijan.

When he arrived at his service point and reported to his regiment’s commander that he had married during his time off, they started cursing him, “Holy shit, you are seriously going to bring a 17-year-old child here. It’s Azerbaijan, prairie with horrible conditions, there is nothing here. Are you out of your mind?”

One of their officers had previously married a girl from Moscow. She came, looked at everything and ran away two days later. That’s why, when I came, all the regiment was watching us. Everybody was interested what will come out of it. And I wasn’t scared. The thing is, I got pregnant really fast. We had a lack of food, ate mostly canned fish, and my milk disappeared. We had Azerbaijani women bring buffalo milk to us.

This was a time when Azerbaijan was the wildest country. As soon as you appeared in the city, a crowd of men started following you. That’s why we’d have to be accompanied by a soldier with a rifle even to buy fruits in the market.

Pilots are a special breed of people. We buried many people in the course of our lives. When we looked at his graduation photo, every third person died in a crash. It was almost like a routine, yesterday your comrade died, today you bury him and tomorrow you go on flying. Just before my husband took his obligatory vacation days, he would fly in a special zone to loopings in the sky. Just so he can live through a month without flying an airplane.

When we moved to Germany in 1960, I was dying to see how Westerners were living. My friend and I ran away to Berlin on a day, when our husbands had night shifts and were to come back after midnight. She could speak German, we were pretty, stylish, and it was impossible to tell us apart from German women. If somebody had found out about it then, we’d would have been deported to back to the U.S.S.R within 24 hours.

Western Berlin astonished us. We were strolling around the city, sat in a restaurant. Suddenly a waiter brings us two glasses of wine. We didn’t order wine. He points at men at the table across us, they bought it. We had a dilemma, what do we do? If we drink it, they’ll think that the contact is established, and if we don’t drink it, we might hurt their feelings. The wine is standing there, and we don’t know what to do. We had our meal fast, paid, chugged the wine and ran away.

My husband and I almost divorced two times. The first time is connected to my son. In the 60s the army lacked recruits due to a demographic pitfall of the 40s. The government started recruiting boys from universities, some men were recruited from prison to join the army. At that point my son was a freshman, and my husband, who had a high rank in the army, would have no difficulty in finding his way to protect his son from the army. But he was a patriot and told our son to serve the country.

On the first day of his service, they took off my son’s sports shoes, jacket, took away his clothes, razors, shampoo. The abuse of new recruits by higher ranks was horrifying. During that period of time I aged a lot, and the situation almost resulted in a divorce.

The second time happened when my husband had problems with his blood pressure, and they didn’t allow him to fly anymore. I was so happy I could not hide it. I didn’t have to wait with my heart sinking each time when a motor roaring suddenly stopped. And my husband hated me for my relief. It was the most difficult period in our life, but he loved me and with time we were able to move on.

It’s been twenty years since my husband is gone. I almost don’t remember the year when he died. He was never sick, and suddenly they diagnosed cancer. He was sick for seven months, and I was with him alone day and night. Later, when he passed away, my son said that they were afraid I would leave with him.

In my life I wouldn’t want to change a single day, even though there were some hard moments. In comparison with my husband, I put my children first. He raised them with this mindset, that I, a mother and a woman, am the most important person in a family. My children treat me this way up to today.

I felt love and deep respect my husband, but not to the same extent, as he did for me. He adored me. They say that in a family one person loves and his spouse lets his husband or wife love him. I let him love me.

This story was first published by Mesto47. You can read this and other stories or listen to a podcast on their site.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.