The former development bank of the Soviet Union is betting on “Europeanization” as it attempts to ditch its legacy of KGB connections and allay international concerns over Russian dominance.

However, the International Investment Bank (IIB) — founded by the former communist economic bloc Comecon in 1970 — is still at the centre of Cold War-era espionage fears, with tension between its chequered history and the new European image it is trying to forge set to sharpen ahead of September celebrations to mark its fiftieth anniversary.

“Of course, we would like to get rid of this Comecon heritage and legacy,” Imre Laszlóczki, deputy chair of the IIB’s management board, told The Moscow Times. “But history is history, and you cannot change what has happened.”

“My big aim is to make the bank more European. It was always a goal, but now we have a real chance, being in Europe. The next strategy will be all about Europeanization.”

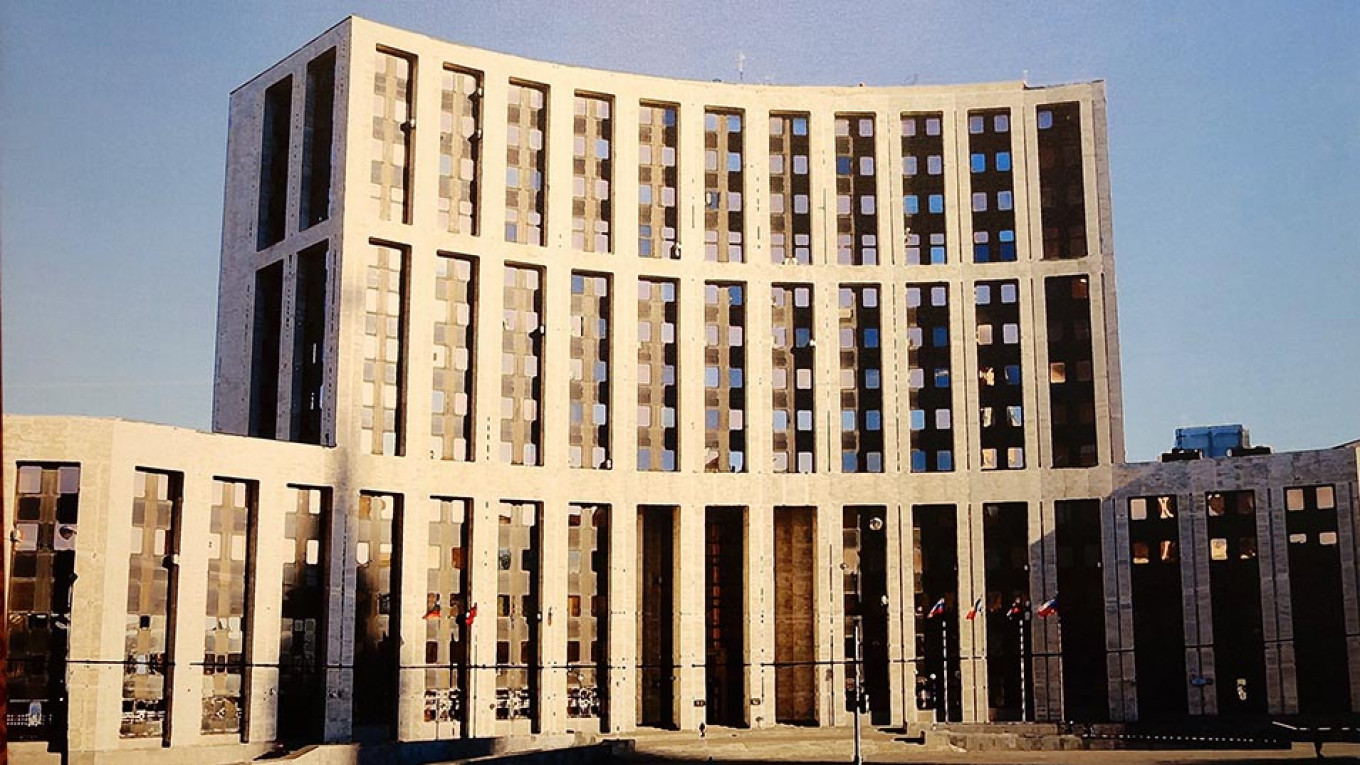

But Europeanization brings increased European scrutiny. IIB’s relocation from Moscow to Budapest, completed last year, was met with uproar from the Hungarian opposition and civil society, while the generous immunities Hungarian President Viktor Orban awarded the bank — diplomatic passports for top staff, full immunity from prosecutorial, financial and regulatory oversight, and guaranteed entry to the EU for an unlimited number of IIB guests — have prompted security fears in Brussels and Washington.

“Imagine an unlimited number of guests with an unlimited number of vehicles and full immunity,” said Hungarian professor András Rácz of the German Council on Foreign Relations. “If I were an intelligence agency operating outside the EU, this is the kind of entry vehicle I’d be dreaming of.”

The U.S. State Department warned the relocation could help Russia “expand its malign influence in Hungary and across the region,” the Financial Times reported last year, and concerns were also raised by British and Canadian officials, said Peter Kreko of Hungarian think tank Political Capital.

Links between the IIB and intelligence agencies were rife throughout the Cold War. The first head of Russia’s Central Bank after the fall of the Soviet Union, Georgy Matyukhin, wrote in his memoirs that he used the IIB as a front organization when he was a KGB operative in the 1970s.

The bank’s current chairman, Nikolai Kosov, who was appointed to revive and Europeanize the IIB in 2012 after it had been left idle since the fall of the Soviet Union, has also been linked to Russian intelligence services.

Expansion plans

The IIB itself has been bullish in pushing back against what it calls “unfounded allegations.” In an interview in the Bank’s newly-downsized Moscow office, Laszlóczki said he found the media coverage “boring.”

Instead, he pointed to the overhaul of its governance structures since 2012, which the World Bank helped with, as evidence that it is serious about becoming an established multinational development bank by 2032. Russia has also reduced its control of the IIB, cutting its shareholding to 43%, while EU members — Hungary, Bulgaria, Czech Republic, Romania and Slovakia — hold 53% combined. The IIB says this proves its European credentials, while critics point to a voting system which means any one shareholder with more than 25% can veto decisions.

The transformation has won support from ratings agencies and investors, who have bought up bonds issued by the IIB in Europe at tight spreads — a signal of strong demand.

“They’ve moved away from being a more Russian-centric institution to becoming a more European institution. With the relocation, the whole culture and base of the organization has shifted to Europe” said Tony Stringer, managing director of global sovereigns and supranationals at Fitch Ratings.

“They’ve made some positive steps in the area of governance and this is an area that since the relaunch they’ve really focused on improving … meaning the bank’s governance structure is now more aligned with international best practice.”

As part of the Europeanization strategy, Russia’s share is expected to decline further. The bank also plans to bring in new countries to add to the current Cold War hangover of nine that includes five former communist EU countries, along with Russia, Cuba, Vietnam and Mongolia. Laszlóczki says there have been preliminary talks with a potential new member in Asia and with unnamed medium-sized European economies.

It remains unclear whether an expansion will materialize. Political Capital’s Kreko said it “would have very bad optics” if another EU member joined the bank, adding that “the Czech Republic is seriously considering abandoning the IIB for security reasons.”

Czech investigative journalists reported that Prague considered pulling out in 2014 but feared losing money it had invested — as was the case when Poland withdrew in 2000.

Relations with Slovakia are also strained after the government vetoed a potential headquarters in Bratislava, refusing to grant the bank the sweeping diplomatic immunities it sought.

Small balance sheet

Without bringing in new members, or securing a significant increase in support from existing ones, the IIB is likely to stay on the margins of international finance, analysts say. By banking standards, it is a tiny player, with 100 employees and a project portfolio of €1 billion, compared to the European Bank for Reconstruction and Development's (EBRD) 2,500 staff and €30 billion.

“The ‘public mandate’ angle — which effectively means how big a player are they, what role they play in the market and how important are they to the shareholders — is a relative weakness,” said Fitch’s Stringer.

“But, they do appear to be punching above their weight. They are the only multinational development bank headquartered in central and eastern Europe, and with this rapid expansion they appear to have become quite a dynamic institution … they are developing a name for themselves in the market.”

Laszlóczki joked that the fears surrounding the IIB’s relocation to Hungary could even have helped raise its profile — putting the bank on the radar of those who would otherwise not have heard of it. But asked whether the IIB can effectively support SMEs, infrastructure and green energy projects, as its mandate stipulates, with such meagre resources, he hesitated.

“It’s the right question. But the most important thing for us now is stability. And then growth. We’re a boutique bank. We will grow, because we want to widen our opportunities and possibilities. But we are going to go step by step.”

An unholy alliance

It was the bank’s “miniscule” size that fuelled concerns over last year’s relocation, with analysts seeing the move not as an economic tie-up, but “as further evidence of an unholy alliance between Putin and Orban,” said Hungarian political analyst Gabor Gyori.

“The problem is, the Hungarian government has cordoned off all of its activities. It is known for its lack of transparency, which leads analysts and journalists down this realm of conspiracy theories. If you don’t have specific information, you need to give your own narratives about what’s happening,” he added.

Expert Russian spy-watcher Mark Galeotti also said the espionage concerns were “overblown,” and that since the relocation last year, he has not heard anything more about them.

Nevertheless, as the bank continues to grow and Europeanize, the scrutiny will remain. Last year several European lawmakers (MEPs) lodged questions in Brussels asking the EU to keep a close eye on the IIB’s activities.

“There is no smoking gun,” says Kreko. “But the circumstantial risks that we are talking about should be taken very seriously.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.