This year, I spent a suffocating four months living inside George Orwell’s “1984.” I didn’t know what I was getting into when a Moscow publisher suggested that I translate the classic dystopian novel into Russian, so I agreed too lightly. Vanity was part of the reason, but I did feel that “1984” had grown relevant to Russians, again.

I’m still coming up for air.

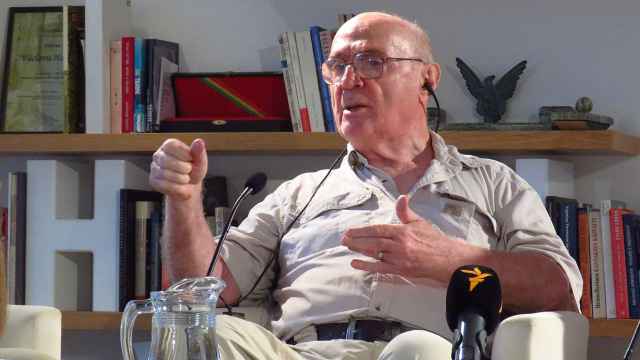

It’s not just me. The eminent translator Viktor Golyshev, whose Russian version of “1984” has won the most acclaim, spent a year on it in the late 1980s. He remembers being chronically sick for a year after finishing it.

“Nothing serious, just a runny nose,” Golyshev, who is 82 now, told me. “But there’s some contamination in this thing. It’s a poisoned book, perhaps because Orwell himself was sick when he wrote it.”

It was probably more than that. Reading “1984” closely — as a Russian, a journalist, and a believer in Russia’s potential to overcome Putinist despotism just as it defeated the Communist variety — is both sickening and cathartic because so much is instantly recognizable. Like my Soviet birth country and Russia today, Winston Smith’s world is both lawless and full of rules, incomprehensible from a human point of view but perfectly logical as a system, indiscriminately cruel and privately lyrical or even heroic.

Most of all, Winston Smith’s world is enclosing, hermetic, stifling. I remember the same feeling from school during the Brezhnev years. I never thought it would be back, not with such force. I felt sorry for Winston, but I knew I was feeling sorry for myself.

Becoming a nonperson

The novel came out in English in 1949, but was banned in the Soviet Union in any language until 1988. To the best of my knowledge, my Russian translation will be the fifth to be published officially. That’s a lot of translations, even for so famous a literary work.

But they’re all different, and not just because rendering Orwell’s newspeak into Russian, along with his descriptions of life on Airstrip One, formerly known as Britain, requires difficult linguistic choices. Each version also reflects its time and its purpose, two factors that are far from trivial when it comes to “1984’s” history in Russia and in Russian.

Orwell himself determined the fate of his work in the Soviet Union. In 1937, the editor of a Moscow literary journal asked him for a review copy of “The Road to Wigan Pier,” a book about the plight of the English working class. Orwell sent back a copy along with a polite note pointing out his association with the Workers’ Party of Marxist Unification, or POUM, an organization whose Barcelona workers’ militia fought in the Spanish Civil War.

Orwell, who’d fought with POUM in Spain, knew the organization had fallen afoul of the country’s Stalinist Communists, influential in the Republican government trying to put down General Francisco Franco’s fascist rebellion. He didn’t think, therefore, that the Moscow journal would want to touch his work. Sure enough, the secret police advised the editor to write Orwell that getting in touch with him had been a mistake, since Trotskyite POUM was “part of Franco’s fifth column behind the lines of Republican Spain.”

The “Trotskyite” label stuck to Orwell, and his work was shunned in Stalin’s Soviet Union. In 1945, Orwell made things worse by writing “Animal Farm,” his dystopian fairy tale mocking the Russian revolution and then, two years later, a preface to the Ukrainian translation. The translation by Igor Shevchenko, called “Kolgosp Tvaryn,” or “Animals’ Collective Farm,” was circulated among Ukrainians in displaced-persons camps in occupied Germany. In his preface, Orwell wrote:

I have never visited Russia and my knowledge of it consists only of what can be learned by reading books and newspapers. Even if I had the power, I would not wish to interfere in Soviet domestic affairs: I would not condemn Stalin and his associates merely for their barbaric and undemocratic methods. It is quite possible that, even with the best intentions, they could not have acted otherwise under the conditions prevailing there. But on the other hand it was of the utmost importance to me that people in western Europe should see the Soviet regime for what it really was. Since 1930, I had seen little evidence that the U.S.S.R. was progressing towards anything that one could truly call Socialism. On the contrary, I was struck by clear signs of its transformation into a hierarchical society, in which the rulers have no more reason to give up their power than any other ruling class.

The Soviet occupation authorities demanded that “Kolgosp Tvaryn” be confiscated. According to a 2014 Orwell biography by historians Yuri Felshtinsky and Georgy Chernyavsky, the U.S. authorities collected 1,500 copies from the displaced Ukrainians and handed them over to the Soviets, but some of the books remained in circulation. There’s a copy in the Library of Congress.

Orwell became a nonperson in the Soviet Union. Mentioning him in print, even to criticize him, became dangerous, as literary critic and translator Eleonora Galperina (pen name Nora Gal) found out in 1947 after her piece titled “Debauched Literature” — in which Orwell was described as a “confused and slippery theorist” — was declared a “serious political error” by functionaries in the Soviet Writers’ Union.

That meant, of course, that a translation of “1984” could not be published in the Soviet Union. In 1958, according to the historian Arlen Blum, an expert in Russian censorship, the Ideology Department of the Central Committee of the Soviet Communist Party actually ordered a translation and a print run of several hundred numbered copies (the translator’s name wasn’t mentioned), strictly for distribution to high-ranking party officials who were supposed to know the enemy better than the masses — to the Inner Party, as Orwell would have said.

But the book was present in the Soviet Union, anyway. There were two main ways to read it: In English, if someone sneaked a copy past linguistically challenged border guards (Golyshev first read a dog-eared paperback of “1984” some 20 years before he did his translation) and in the first Russian translation published overseas. First serialized in the emigre magazine Grani in the mid-1950s, it appeared as a book in 1957 in Frankfurt, courtesy of Possev-Verlag, a publishing house run by the People’s Labor Union, an anti-Soviet emigre organization. The group got the rights and even a subsidy from Orwell’s widow, Sonia.

The treasure in the closet

I first learned of the existence of “1984” when I was 11 or 12 years old. Digging around in a closet in our Moscow apartment, I stumbled upon a sheaf of yellowed Possev magazines, full of stories of brave dissidents and Communist oppression. My scandalized mother discovered me sitting on the floor engrossed in the forbidden literature and took the magazines away lest I brag about it at school. But I’d already seen the list of books the publishing house was selling — “1984” was on it — and memorized the titles so I could ask around for the unofficial bootleg copies known as samizdat.

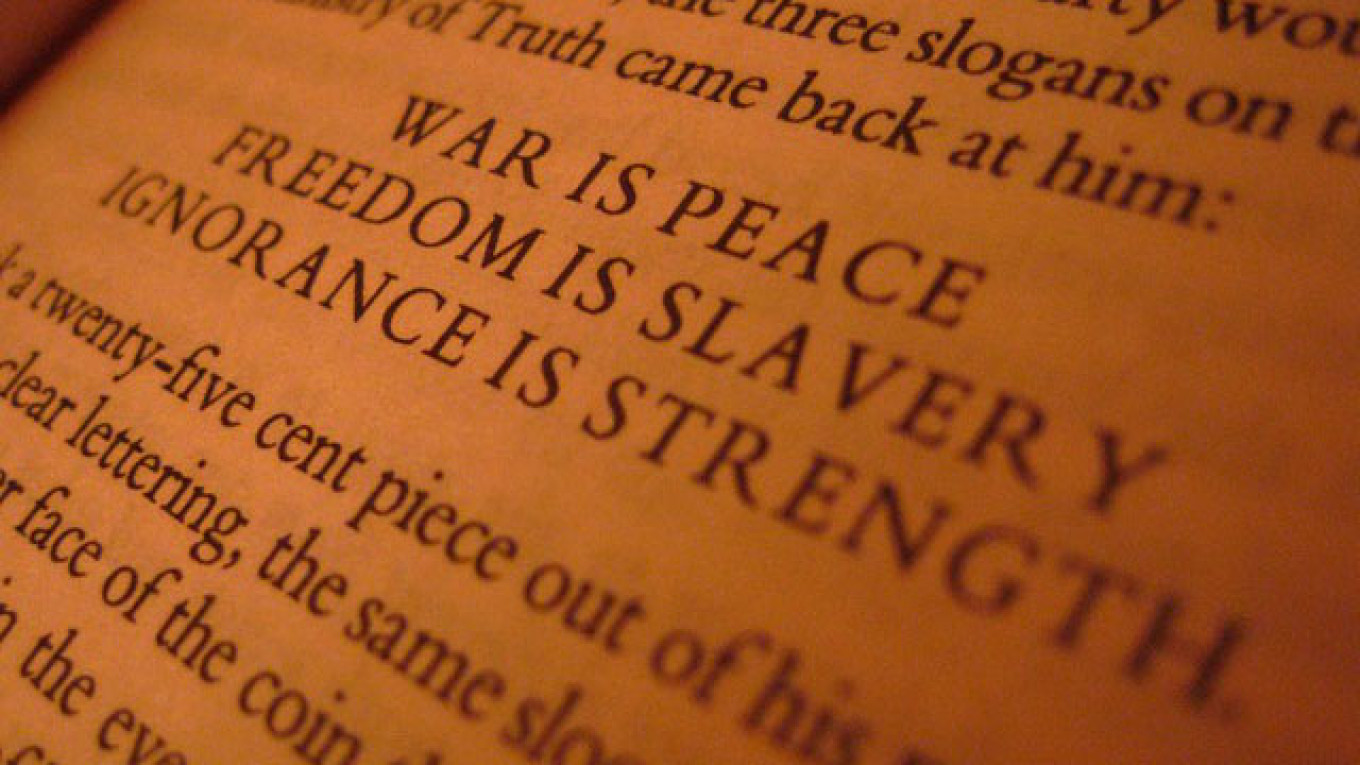

The translators’ names were, according to the cover, V. Andreev and N. Vitov. Both are pseudonyms, one of a White Russian emigre professor, the other of a former Nazi collaborator. Their product doesn’t read well today, whether or not you're familiar with the original. It doesn’t appear that the translators had a good enough command either of English idiom or of proper literary Russian. The writing is stilted. “Big Brother is watching you,” is rendered as “Starshy brat okhranyayet tebya,” or “Big Brother is guarding you.” The word “telescreen” is merely transliterated. The linguistic annex on newspeak at the end, which holds the key to the entire novel because it implies that the totalitarian regime of Oceania fell at some point, is simply missing. No wonder; it’s the hardest part of the book to translate.

But the Andreev-Vitov translation served its purpose. So did various amateur versions one could stumble upon, and so did the second professional one published as a book, in Rome in 1966. Done by Soviet writer and journalist Sergei Tolstoy from the French edition of “1984” — and therefore woefully imprecise — it had mysteriously leaked to the West and then back to the Soviet Union.

Not many people cared about style when they only got a barely readable typescript or photocopy for one night. As the late dissident Valeria Novodvorskaya recalled in 2009,

Orwell was the treasure of Samizdat. When I first saw [“1984”] in the early 1970s, it was a cumbersome, disheveled folio in a worn, cardboard cover, on tissue paper. The translations were bad, clearly homemade. Some had “teleekran,” some “telekran,” some even “telescreen.” But it was clear that it’s a TV camera, an eye that never sleeps, a watcher. “Alike and alone,” we got it.

She remembered that in some versions of the translation, Big Brother was rendered as Starshiy Brat, which translates literally as “Older Brother,” in others the more size-conscious “Bolshoi Brat,” but said “it was clear he was Stalin,” or a fearsome figure like Yuri Andropov, the KGB boss who rose briefly to national leadership after the 1982 death of Leonid Brezhnev.

Novodvorskaya went on: “Orwell was worth his weight in gold, or in blood. Not every kind of Samizdat landed you in prison under Article 70 of the Criminal Code, and Orwell did. It was worth more than life: We believed that once people read ‘1984,’ totalitarianism would fall.”

Orwell’s novel did something important for its Soviet readers: It described the reality around them as something abnormal, and that made it tolerable. Suddenly, it wasn’t their fault that they saw it all as both criminal and surreal. They were no longer part of the evil. In 1977, writer Anatoly Kuznetsov, by then an emigre, explained this in a Radio Liberty broadcast:

“It didn't happen,” they say of something that happened. Before, I used to get really excited when I came across this. But after reading George Orwell’s “1984,” I calmed down somewhat about it. It was a philosophical kind of calm, probably not wisdom, more like self-defense, otherwise my nerves would get too frayed.

Meanwhile, the Soviet regime, still thoroughly Orwellian in the way it handled information, gradually grew more vegetarian, or perhaps simply less bloodthirsty. In 1982, there was even an entry about Orwell in the official Soviet Encyclopedic Dictionary; written in a kind of newspeak with characteristic abbreviations, it probably would have brought a grim smile to Orwell’s face:

Engl. writer and essayist. From petty bourg. radicalism, moved on to bourg. liber. reformism and anti-Communism. Antirev. satire “Animal Farm” (1945). Dystopian novel “1984” (1949) depicts society succeeding capitalism as totalitarian hierarch. system. Petty bourg. radicals consider O. a “new left” precursor.

By the time 1984 rolled around, it was perfectly fine to mention Orwell in print, and Melor Sturua, a top Soviet foreign correspondent and propaganda guru, penned a grandiloquent piece in the government newspaper Izvestia explaining that while Orwell had meant his novel as a “caricature of our system,” he ended up predicting the West’s moral bankruptcy.

“No, this isn't the ideal of socialism, this is the daily routine of capitalism," Sturua wrote. “The animal existence of the proles is its goal.” It was in the decaying West that the rich surveilled and oppressed the poor, the Pentagon preached that “War is peace,” Augusto Pinochet brutalized Chile and the apartheid government of South Africa erased the truth and vaporized truth-seekers.

By dragging Orwell out of nonpersonhood, the late Soviet ideologists — who still considered him an anti-Soviet propagandist — were gradually making the official publication of “1984” inevitable. It was one bit of evidence that the Soviet system was fraying.

Proceed With Caution

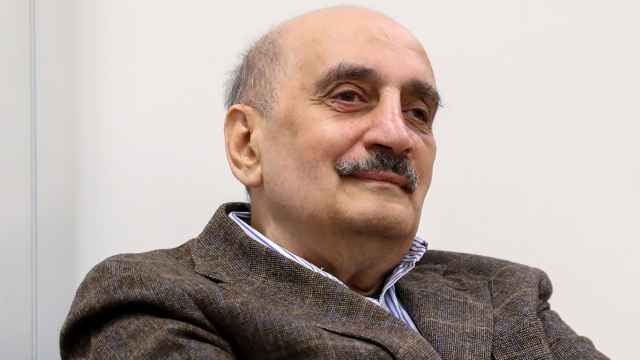

In 1982, Vyacheslav Nedoshivin, a leading journalist at the main Young Communist League newspaper, Komsomolskaya Pravda, was accepted to the doctoral program at the Communist Party’s Social Sciences Academy (there was a place in it every year for the influential paper’s staff). Nedoshivin had read a samizdat translation of “1984” back in the 1970s and became interested in dystopian literature. So he decided to write his thesis about the genre — which meant discussing not just Orwell but also Aldous Huxley and Yevgeny Zamyatin.

“If there was any place where I could take on such a subject, it was there, at the epicenter of ideology,” Nedoshivin told me via email when I contacted him for this story. The Academy’s department of cultural theory and history turned out to be full of liberals, and they were all for it. Nedoshivin’s work was titled, perfectly in line with the orthodoxy of the time, “A Critique of the Ideological Concepts of the Modern Bourgeois Dystopian Novel” — but it was, as far as anyone knows, the first serious academic work in Russia that discussed Orwell. It included, according to Felshtinsky and Chernyavsky, who are by no means nostalgic for the Soviet era, some "objective and rather precise judgments” on his work. At 74, Nedoshivin is still passionate about Orwell, and last year he published a popular biography of the writer.

Nedoshivin got his doctorate in 1985, the year Mikhail Gorbachev came to power and censorship began weakening so fast that the Russian literary world couldn't believe it. In certain ways, there was more freedom to publish during Gorbachev’s perestroika period of restructuring than at any other time in Russian history. There was no working copyright law, either.

Caution was still required, of course. In 1987 or 1988, a contact at a publishing house asked Golyshev to translate ‘1984’ for him — without an official contract. The translator took the plunge into Winston Smith’s world without any guarantees that anything would come of it. He’d often done this before, but this time he was especially doubtful. “I thought this freedom might last for a year,” he told me.

The publisher wouldn't accept his work, so Golyshev handed his finished translation to another one, which released a minuscule print run of 1,500 in 1989. Then the original publisher turned around and brought out the book too — such was the time. But by then, Golyshev had heard vaguely that he’d been beaten by “some guy from Riga who published his translation in Moldavia because people wouldn't risk it in Riga.”

It wasn’t “some guy from Riga.” It was Nedoshivin. Thirty years later, Golyshev learned this from me. The freshly minted Ph.D. did a translation of his own with the help of an English teacher who hid behind the bland pen name Dmitry Ivanov. “It took me nine months, like carrying a child,” Nedoshivin told me. As for Golyshev and later for me, it appears to have been a visceral experience.

Nedoshivin published his work in Kodry, the literary journal of Soviet Moldavia, now Moldova, in 1988. Had he waited a year, he would have discovered, as Golyshev did, that now Moscow was ready, too.

The translations of Golyshev and Nedoshivin are the best known ones today. Unlike the earlier samizdat and emigre versions, both are professional jobs. Golyshev's is more polished and literary, Nedoshivin’s more concerned with precision than with flow. Perhaps most importantly, both Golyshev and Nedoshivin made a capable effort to render words coined by Orwell into credible Russian. Words like “novoyaz” (newspeak in both Golyshev's and Nedoshivin's translations), “mysleprestupleniye” (thoughtcrime, according to Golyshev), “telekran” (telescreen in Golyshev's version), “proly” (proles in both versions) and “Bolshoi Brat” (Big Brother in Nedoshivin's translation) are part of Russian usage now.

Crooked Thinking

I hadn't even leafed through either translation by the time I took on “1984.” I’d read the book three times, always in English. At 19, as a novice journalist, I treated it as an inoculation against propaganda — but it seems to me now that I simply wasn't able to read it slowly enough back then. By the age of 30, I had enough experience to appreciate the book’s other layers. That reading turned out to be about confronting my fear of physical pain by following Winston Smith’s ordeal in the final part of the book. At 40, at a time of personal and professional crisis, the love line — Winston’s doomed affair with Julia — suddenly blossomed for me.

I didn't worry too much about the politics. All three times, I skimmed impatiently through the geopoliticial and social analysis Orwell put into excerpts from a book purportedly written by Emmanuel Goldstein, Oceania’s Trotsky-like Public Enemy No. 1.

Then I got the message from the publisher. Today's Russia has working copyright laws. Orwell died in 1950, and the rights to his work will enter the public domain on Jan. 1, 2021. It was an opportunity to do the first translation since Soviet times.

My work has been done for a couple of months. But it’s only now that I’ve looked at the Golyshev and Nedoshivin translations that I’m reasonably convinced that a new translation isn’t entirely pointless.

One reason is that I appear to have approached Orwell's text from a different angle. Golyshev told me he’d done the linguistic annex last. I started with it, trying to imagine Oceania's system through its approach to reforming the language first. This gave me something of a scholarly perspective — and, in retrospect, made it a little easier to live through Winston's personality-obliterating experience. I’d started with the idea that this, like any tyranny, isn't forever, that a pendulum may swing too far but it’ll always come back.

I made some different linguistic decisions than the eminent translators. “Mysleprestupleniye” (thoughtcrime) seemed too cumbersome for Orwell's paradigm of chopped, clipped portmanteau words, and I came up with the shorter “krivodum” (literally, crooked thinking). I rejected the customary “novoyaz” for newspeak in favor of “novorech,” as in the Possev translation, because Orwell's word implies new speech, not a new language (this is where Golyshev disagreed with me when I asked him).

Perhaps the most controversial choice I made was about the rendering of Ingsoc, the name of the Oceanian ideology.

All Russian translators before me decided on “angsots,” preserving the first syllables of “England” and “socialism” as the building blocks. I settled on “anglism” — not just for a clearer parallel with “animalism” in “Animal Farm,” but also as part of a generally eclectic approach meant to unlink the text from associations with the specific leftist kind of totalitarianism. “Anglism” sounds more like a jingoistic system than a redistributive one; to me, this term fits Oceania, with its never-ending war fever, better than the accepted one that stresses socialism rather than nationalism.

I thought of the Putin regime, which rejects socialism and focuses on patriotism and military victories as the foundation of the national ideology. I thought of Brexit and the way its proponents use Britain's World War victories. I thought of the U.S. and German nationalists of today. None of that background was there in the 1980s, but it’s what went into my translation.

In the late 1980s, Golyshev, the consummate professional, was wise to avoid Soviet jargon and specific Soviet newspeak words known to the people of the Soviet Union. “I knew the jargon would soon die off and be forgotten,” he told me. “Why shorten the book’s life by using it?”

Still, like everyone at the time, Golyshev read “1984” as a book about the Soviet experience. How could he help it? As he put it:

It was all very personal. That cafeteria, I’ve eaten in a cafeteria like that, with meat products that didn't look or taste like meat, and my jacket stank of burned oil when I left. And the razor shortage. I remember a guy offering to trade me a fish for a razor.

Back in the U.S.S.R.

So no matter how Golyshev tried, his translation sends me back into the country I grew up in, the Soviet Union. I don't want to go there. Thirty years later, it's easier to put some distance between “1984” and Soviet life.

But that alone wouldn't justify a new translation. A novel rendered into another language isn't just shaped by the translator's professional preferences and technical prowess. It inevitably carries traces of the intermediary’s worldview.

Both Golyshev and Nedoshivin say they see 1984 as prophetic, but in different ways. For Golyshev, the surveillance part is the most striking. “Anything that has a camera is watching you,” he says. But he doesn't see the oppressiveness of Oceania's system as particularly relevant to the present. “These days, we tend to think that whenever someone gets squeezed a little by the state, it's the end of the world,” he told me. "But it’s not at all the same thing as in the 1940s. I've been there, I remember.”

Nedoshivin, for his part, even sent me a list of what he considers Orwell’s fulfilled prophecies: The shrinking of basic freedoms everywhere in the world, the rewriting of history, double standards in foreign policy, the erosion of language and culture, even “the gradual elimination of the family, childbirth and gender differences.” As he put it in an email:

In my opinion, thanks to the internet, the world is growing more uniform despite borders and different social systems. The ways of life, the methods of governance, the all-pervading globalism, the unwritten laws of the “golden billion.” I have no illusions, no hopes for either the West or the East, which are growing more and more alike — like people and pigs in “Animal Farm.”

One reason I'm convinced now that another translation is needed is that I disagree with both Golyshev and Nedoshivin. At 48, reading “1984” for the fourth time — and living it for the first time, an experience few want or can afford — I came away with the feeling that it's still an unfulfilled prophecy.

Regimes, including the current Russian one, try various bits of the Oceanian recipe. They search for external enemies, demand blind loyalty, use increasingly sophisticated propaganda, surveillance and suppression methods. It can get really bad — worse, in some individual cases, than even in the 1940s.

But the O’Briens of today, the agents of despotic rule, are still repeatedly thwarted by individuals who refuse to think as they're told. In “1984,” Winston Smith ends up the loser. But thanks to the newspeak annex, we know that the system ultimately lost. Somehow, Winston's rebellion wasn't entirely wasted.

“We miscalculated,” Novodvorskaya wrote in 2009. “Orwell sits on bookstore shelves, it's 2009, but peace is war again… Russia wants again to be ‘the boot that tramples the face of humanity’; and ‘Big Brother’ V.V. Putin smirks down from posters and portraits.”

I disagree. Nothing is over yet. The version of “1984” that I tried to present is one where the pendulum doesn't just swing in one direction, in Russia and elsewhere.

But here's the problem: I still can't get rid of the feeling that Winston and I are the same person. Golyshev told me he never reread his translation or the original after finishing his work. I think I know why. Shaking off this book is much harder than professing optimism.

This article was first published in Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.