Can billionaires be good, honest people?

Alexander Lebedev, a Russian oligarch turned philanthropist and media mogul, certainly wants us to think he is.

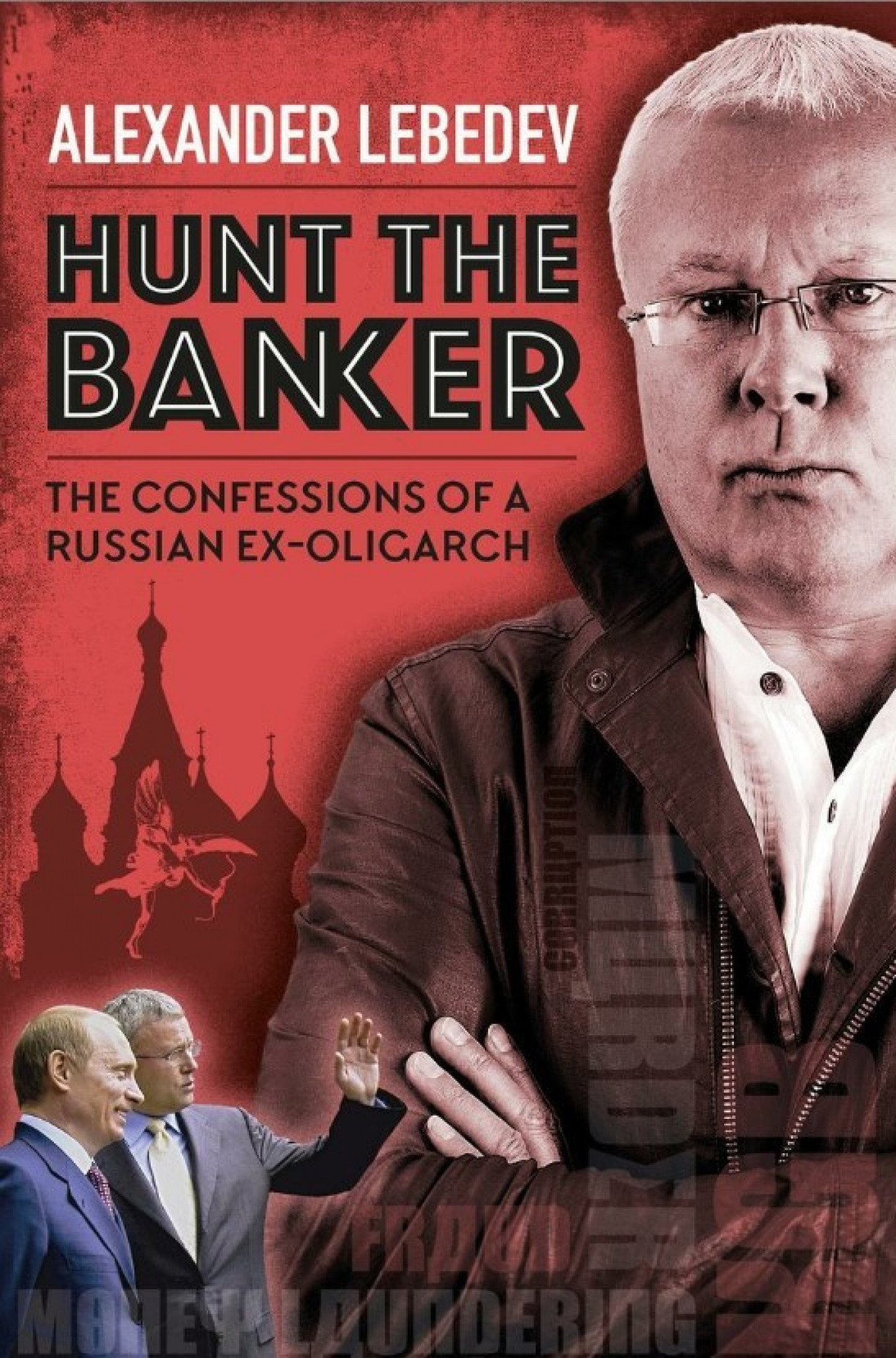

His new memoir, “Hunt the Banker,” begins with a preface that laments the burdens of immense wealth. Lebedev confesses that the millions he made during the unbridled capitalist 1990s have brought him more hardship than good.

From there, he recounts his rise from being a KGB intelligence officer in the Soviet embassy in London to earning immense wealth as a banker in the 90s and eventually falling from grace in the early 2010s when his holdings were stripped from him. He also shares how he came to own two major British newspapers, the Evening Standard and The Independent.

Along the way are candid retellings of business disputes, an assassination attempt and encounters with world leaders — one of which, with then-London Mayor Boris Johnson, is now at the heart of a political battle in Britain.

He weaves in documents, newspaper clippings and transcripts of conversations to support many of his accounts, often revealing never-before-seen details. If you think you know what happened at a certain meeting or a particular event, read “Hunt the Banker” to get an entirely different version.

As translated by the renowned Arch Tait, Lebedev's story is entertaining and his tone is frank and funny. With international intrigue, siloviki and crooks and the cutthroat stakes of Russia’s highest echelons,“Hunt the Banker” is the real-life account of someone who’s seen firsthand the inner workings of today’s Russia — and made it out to tell the tale.

From Chapter 2: The Xerox Paper Box

'Choose or Lose!'

...Most of those called oligarchs became rich thanks to the state, and were perfectly aware that it could, whenever it chose, reduce them to penury. That was the fate of Vladimir Vinogradov, who died a poor man. The entire Menatep coterie ended up in jail or emigration, and Berezovsky came to a bad end. Oleg Deripaska, the owner of Rusal aluminium, very succinctly articulated the Russian oligarch’s credo in a 2007 interview with the Financial Times. ‘If the state says we must renounce (the company), we shall do so. I do not see myself as separate from the state. I have no other interest.’ This is why the oligarchs, with the exception of Berezovsky, have either steered clear of politics completely, or preferred not to keep all their very valuable eggs in one basket. The renowned Seven Bankers went out of their way to find opportunities, if not to do a deal with the Communists, then at least to square the circle. In April 1996, Nezavisimaya Gazeta (Russia’s Independent Newspaper) published a letter, ‘Let’s End This Deadlock’.

It was signed by all seven of the bankers, as well as by Sergey Muravlenko and Victor Gorodilov, the CEOs of the Yukos and Sibneft oil companies (which were not at that time owned by Khodorkovsky and Abramovich); by Alexander Dondukov, president of the Yakovlev Experimental Design Bureau; Nikolai Mikhailov, president of Vympel International Corporation; and Dmitry Orlov who owned the Vozrozhdenie Bank. In their letter, crafted by Sergey Kurginyan, who was close to the Communists, they upbraided both Democrats and Communists and called upon them to ‘make a concerted effort to find a political compromise and avert dangerous conflict.’

Yeltsin, however, was not a man of straw, but a charismatic politician with a startling appetite for power and a nose for anything that threatened it. When he saw plainly that Soskovets and his team were heading for defeat, a new campaign team under Anatoly Chubais suddenly appeared. The key players in it were Yeltsin’s daughter, Tatiana Diachenko, and Viktor Ilyushin, who had been Yeltsin’s assistant since he was first secretary of the Moscow City Communist Party Committee. Unlike the bureaucrats and security ministry people, they recognised that relying solely on administrative resources would get them nowhere, and that popular support now needed to be worked for using capitalist methods.

They launched an ambitious public relations offensive, ‘Choose or Lose!’ To this, advised by the top experts in the newly emerging art of spin-doctoring and by talented directors of Russian show business, they attracted to their banner the famished creative intelligentsia, the celebrities of art and culture. All this, of course, came at a considerable price but, also of course, the money was not paid through this presidential candidate’s election fund.

The bankers really did shell out for Yeltsin’s election campaign, but less from fear of the Communists or from any great love for the ruling regime than because, as would have been the case in Soviet times, the incumbent told them it was their duty. He also provided them with tools for the job that enabled them, even as they financed his campaign, to make a little money for themselves.

A pyramid for Yeltsin

A neat fundraising mechanism was devised. Selected banks invested money the Ministry of Finance had on deposit with them in government short-term bonds, a financial pyramid created by the ministry itself. Everyone participating in the market at that time bought the bonds, because the return was ridiculously high: over 100 per cent per annum and, one might assume, with no risk attached because they were, after all, state bonds. Deputy Finance Minister Andrey Vavilov sent round a memorandum to banks who were using the ministry’s money in this play, stipulating that half the income was to go to the Yeltsin campaign fund, in cash. That was the source of Yeltsin’s election slush fund, of which more below.

It had a very specific address: No. 2, Krasnopresnenskaya Embankment, which happened to be the head office of the Government of the Russian Federation, known as the White House. It was a perfect location for dispensing cash – a hypersecure facility with all amenities, including an almost free canteen and a ready supply of alcoholic beverages.

Cars bringing money drove in directly from the embankment. There were two teams at work in adjacent rooms. One, under Alexander Korzhakov, who headed the president’s personal security service, received and counted the cash and put it into wads. The other, delegated from Chubais’s headquarters in the President Hotel on Yakimanka, collected it for current expenditure and removed it from the building. In between performing these important patriotic duties, the lads drank brandy, smoked, played computer games (the Internet was not yet available, so they played Solitaire or Minesweeper) and hung around the young White House secretaries and waitresses.

Throughout the campaign, this mechanism worked like clockwork. Crafty Berezovsky and Gusinsky avoided having to pay the cash by persuading campaign headquarters they would make their contribution by exploiting their television channels, ORT (now Channel One) and NTV. Ordinary bankers from the coalface were rather miffed they were having to shell out their honestly acquired cash on propaganda, rather than just issuing orders to the menials who managed TV channels for them, but could not make specific complaints for lack of evidence.

National Reserve Bank, like other donors, dutifully paid over the prescribed amounts to campaign headquarters. The money was used to send pop stars all over the country to urge their fellow citizens attending gigs to ‘vote with your heart’. Ten million copies of a free colour newspaper, God Forbid!, were printed and explained that Zyuganov was worse than Hitler. The Communists were regularly lambasted on the airwaves.

As a result, in the first round of the election, held on 16 June, Yeltsin overtook his main rival, gaining 35 per cent of the vote against Zyuganov’s 32 per cent. They went through to the second, decisive round, held on 3 July. Yeltsin managed to strike a deal with General Alexander Lebed, who unexpectedly came third with an honourable 14.5 per cent. On 18 June Lebed was appointed secretary of the Security Council ‘with special powers’, and publicly endorsed the incumbent president. Chubais’s headquarters were all ready to open the champagne, but the very next day something unexpected happened.

That Wednesday our staff, as usual, brought another instalment of ‘sponsorship donations’ to the White House in our bank packaging. Actually, it was two instalments. Yeltsin’s headquarters were preparing a final mega-concert in Red Square and needed a whole bunch of money. Sergey Lisovsky, one of the pioneers of Russian show business, whose remit at Yeltsin HQ was the ‘Choose or Lose!’ campaign; Chubais’s assistant, Arkadiy Yevstafiev; and seconded from our bank, staffer Boris Lavrov, appropriated $538,000 of the money they had been brought for preparations for the event, put it in the first box to hand (which happened to be for photocopier paper) and walked serenely towards the exit.

Right by the entrance, all three were detained, sent for questioning, and the money was confiscated. There was a great scandal. Chubais, speaking on television, all but accused Korzhakov, FSB Director Mikhail Barsukov and their ‘father confessor’ Soskovets, of attempting a coup aimed at disrupting the election. All three were fired the following morning.

The motive behind the security officials’ action would probably be comprehensible only to a very heavy drinker. Conceivably, the minions of Korzhakov and Barsukov were jealous because the minions of Chubais were walking away with the lion’s share of the cash. Years later, Korzhakov described the incident as a move against embezzlement at Yeltsin’s campaign headquarters. Militating against this is the fact that his own people were sitting in the next room, knew perfectly well how much money the couriers were taking and why, and had actually allocated them the disputed $538,000.

The only rational explanation for the whole episode seems to me to be that a person or persons were drunk out of their mind. The Presidential Security Service officers, who were working as the campaign’s cashiers, were indeed seriously imbibing while on duty and may simply have forgotten what they were supposed to be there for. To cap it all, according to people involved in the event, a vehicle bearing $5 million was on its way to the White House but, after the incident, vanished without trace.

At Yeltsin’s headquarters it occurred to someone to pass the buck to … me. Well, who else but the ‘ex-KGB agent’ must have set the whole thing up in cahoots with Korzhakov? I suspect the source of the rumour was Gusinsky, in order later to demand an interbank loan to prop up his TV-Most, which was becoming seriously wobbly. Until Chubais was able to run to Yeltsin and turn the situation to his own advantage, he was very cross.

In the evening, I was summoned by Vavilov, the campaign treasurer, to his dacha. He was in a foul mood. His young new wife, with whom Andrey was head-over-heels in love, had a flaming row with him in front of me. He went straight on to blame me for the disaster with the ill-starred Xerox box. I had landed everybody in it. I tried to reason with him. ‘Just a minute, guys! Someone tells me a car is on its way, I fill up a box, the car goes off with it. This is not the first month that’s been going on. What am I being blamed for?’

Excerpted from “Hunt the Banker. The Confessions of an Russian Ex-Oligarch” by Alexander Lebedev, translated by Arch Tait, published by Quiller Publishing Ltd.

Copyright © 2019 by Alexander Lebedev.

Used by permission. All rights reserved.

For more information about the book, see the site.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.