On Oct. 27 Vladimir Bukovsky, one of the most important figures in the human rights movement in the Soviet Union and the world, died of heart failure in a hospital in Cambridge, U.K. He was 76 years old.

Bukovsky was born in what is now the Republic of Bashkortostan and soon moved to Moscow, where his father became a prominent journalist.

Bukovsky was an independent thinker from an early age: he was expelled from grade school for editing an unsanctioned magazine. After making up his missed classwork, he was accepted into the biology department of Moscow State University in 1960 but was expelled a year later for his samizdat (self-published) writings critical of the Komsomol (Communist Youth League) and other dissident activities.

This marked the beginning of a long period of Bukovsky’s incarceration in psychiatric prison hospitals — diagnosed with “sluggish schizophrenia,” the mythical mental ailment said to afflict Soviet dissidents — as well as jails and prison camps. Whenever he was released, he resumed his activities to organize rallies in support of dissident writers and activists, such as Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuly Daniel, and to publicize abuse of civil and human rights.

After a total of 12 years behind bars, in 1976 he was traded for Luis Corvalan, the imprisoned secretary of the Chilean communist party. Bukovsky settled in Cambridge, where he completed his degree in biology, and continued to write and work in support of human rights and against Soviet and Russian oppression, as well as Western complicity. He was a relentless critic of any abuse of power anywhere in the world.

Among his most important work was publicizing the abuse of psychiatry to punish Soviet dissidents. In 1971 he smuggled out of the country materials documenting the use of psychiatric hospitals to house and torture political opponents to the Soviet regime.

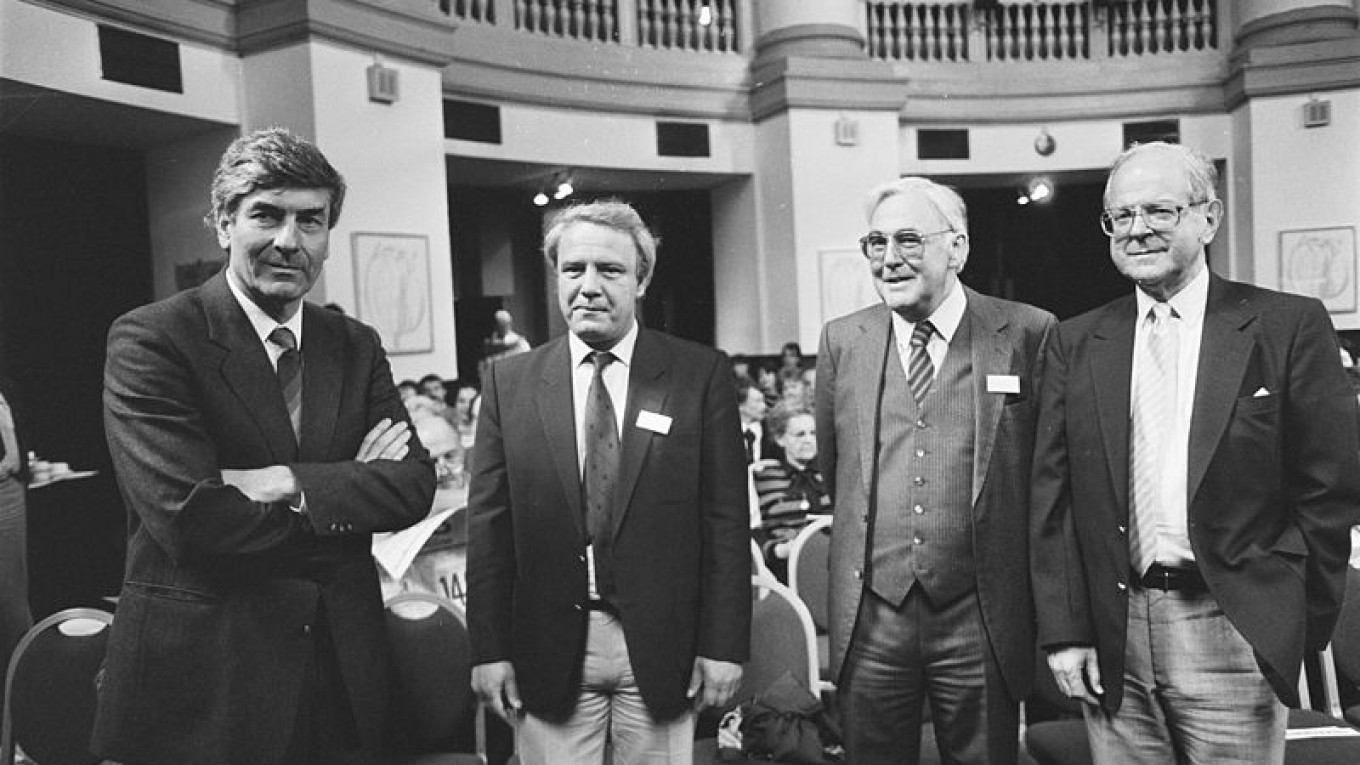

Over the years he met with many of the world’s leaders, including U.S. presidents Jimmy Carter and Ronald Reagan, and Margaret Thatcher. He was invited by Boris Yeltsin to return to what was still the Soviet Union in 1991 and took part in the “trial of the communist party” that was held in 1992. Supporters in Russia proposed his candidacy for mayor of Moscow and president of Russia in the 1990s, but only in 2008 did Bukovsky attempt to run for political office in Russia. However, his candidacy for the presidency was disallowed due to residency requirements.

Bukovsky was an outspoken critic of any country that committed abuses against its citizens, writing prolifically against the use of torture in the Guantánamo Bay detention camp, Abu Ghraib and the CIA secret prisons. He wrote about violations of human and civil rights in the European Union and other western countries while continuing to speak out and write against the increasingly authoritarian regime in Russia and the revival of Soviet methods of oppression.

In 2015, he was accused by the U.K. Crown Prosecution Services of possessing prohibited images of children allegedly found on his computer. Bukovsky charged that they were placed on his computer through a backdoor program by the Russian secret services, which then tipped off the British authorities through Europol. Due to his poor health and lack of substantiating evidence, the trial was postponed indefinitely.

Bukovsky was a member of many organizations including Resistance International, Human Rights Foundation, the Cato Institute, the Victims of Communism Memorial Foundation, Committee 2008, and Solidarnost.

He was the author of hundreds of articles and dozens of books, from his best-selling “To Build a Castle: My Life as a Dissenter,” written in 1978, to “Judgment in Moscow: Soviet Crimes and Western Complicity,” published in 2019.

Funeral arrangements have not yet been made public.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.