This summer, images from Russia of police beating protesters with batons and dragging them off to armored vans flashed across the world’s screens so often they became routine.

Sparked by the arrest of an investigative journalist on fabricated drug charges, the mass rallies then became weekly affairs after opposition politicians were blocked from running in Moscow’s city council elections.

Against the backdrop of a long history of crackdowns on public assembly, the authorities’ response may not have come as a complete surprise. What might have, though, was that, among the wider public outcry, a sports website was taking a political stance on the events.

“The arrest of Ivan Golunov is an encroachment on the ability to speak the truth,” the editors of the Sports.ru outlet said in a statement after the reporter’s arrest in June. “This isn’t something distant that doesn’t apply to sports journalism. This is about everyone.”

The outlet also backed up its words with actions.

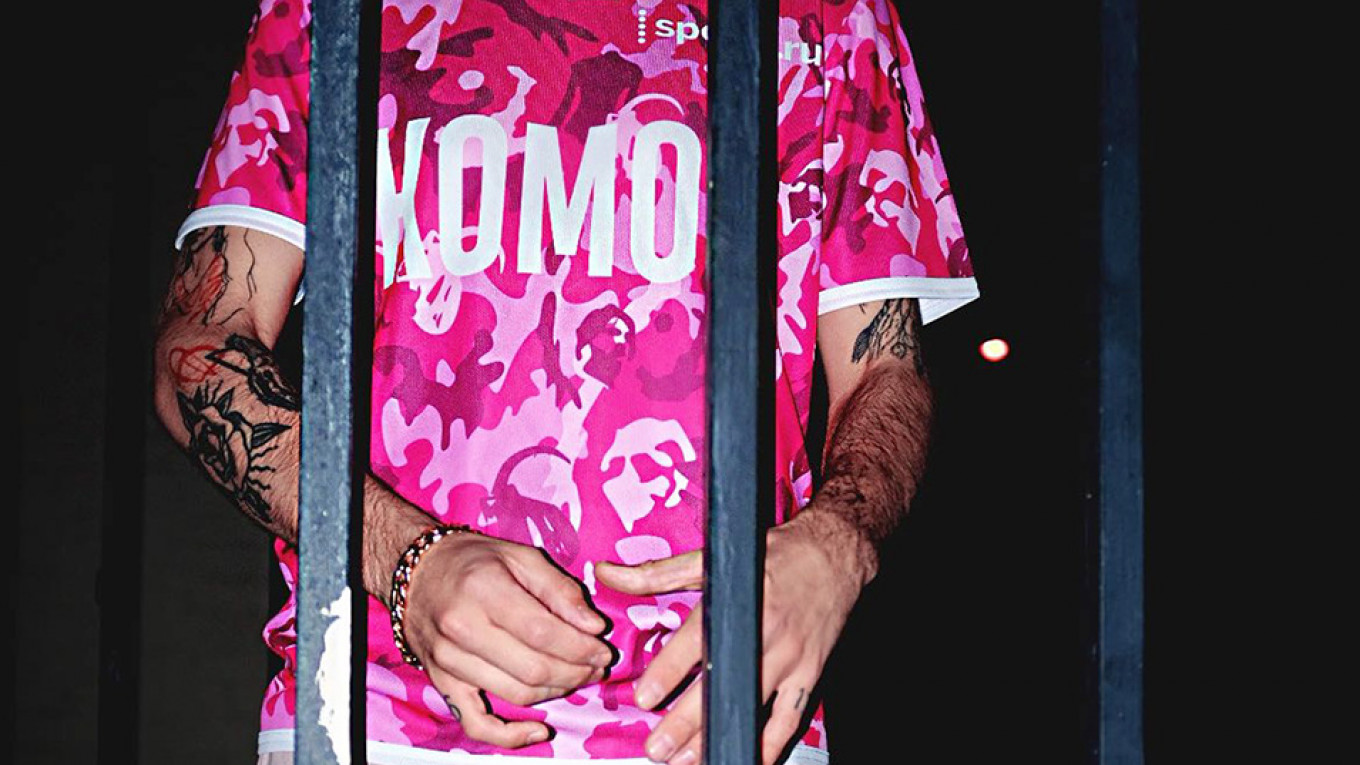

Two days before a rally at the end of last month in support of those facing lengthy prison sentences for taking part in the summer’s protests, Sports.ru released a collection of merchandise. The soccer jerseys, T-shirts and iPhone cases in fluorescent camouflage print all have the word “КОМОН” printed on them, a Russian play on words for “C’mon, OMON” — the Russian riot police. The proceeds, the outlet said, would be going to the OVD-Info volunteer organization that helps detained protesters.

Yet for those who have closely followed Sports.ru’s rise, its stance on Russia’s summer of discontent is a natural expression of its DNA. More than just a sports website, the outlet has become a home for topics of discussion that are taboo in most other venues in the country.

“Be it feminism or the fight against racism or homophobia, sports don’t exist in a vacuum,” Sports.ru’s co-founder Dmitry Navosha, 41, said in an interview in his office in a business center a stone’s throw from the Kremlin. “They’re intertwined with everything, which is reflected in sports like the reflection in a raindrop.”

Founded in 1998, Sports.ru was the brainchild of several like-minded journalists, including the popular blogger Yury Dud, who saw sports not just as scores and stats, but also as a cross-section of culture, politics and economics.

Glance at the website today and you’ll find articles covering a spectrum of topics: a column calling for focus on American tennis star Serena Williams’ play rather than her looks; a deep dive into the history of Soviet propaganda in sports; an article explaining that the professional Russian soccer league’s economics are flawed because most of its clubs are run by the state, or state-run companies.

“This intersection of sports with politics is especially the case in Russia, where sports are highly economically dependent on the state and developed mainly by its initiatives, including those of Vladimir Putin personally,” Navosha said.

The reason, said cultural commentator Yury Saprykin, pointing to the 2014 Sochi Winter Olympics and the 2018 FIFA World Cup, is that the authorities use sports to fire up patriotic fervor.

“In the 2000s, the authorities made sports a kind of proxy war,” Saprykin said. “If Russia does well in the Olympics, it shows that ‘ours are better than theirs’ and that Russia has become great again.”

That context, coupled with the fact that Putin’s government has made operating as an independent media company in Russia a difficult proposition since he first came to power at the turn of the century, means that, in theory, the journalists writing for Sports.ru should skirt around sensitive topics.

They don’t. To highlight one example, when Russia’s state-sponsored doping program for the Sochi Games came to light, Sports.ru covered the story extensively.

“It’s a miracle that a sports outlet like this exists in Russia right now,” said Saprykin. “It’s a testament to how they’ve built their business.”

“Navosha is the smartest media businessman not only in Russia but in all of Eastern Europe,” said Vasily Gatov, a Russian media researcher at the University of Southern California’s Annenberg Center on Communication Leadership & Policy.

A big part of Navosha’s success, Gatov said, comes from Sports.ru’s financial independence from the state.

The main way he has cultivated this has been by developing a platform that allows users to write their own blogs that are published with open comment forums. In this way, the outlet is less traditional media and more what Navosha describes as “ESPN meets Reddit” — the American sports media giant and the social discussion website.

“We quickly realized that to survive, just having content that you couldn’t find elsewhere wasn’t enough,” Navosha said. “Our competition is outside of the market,” he continued, pointing out that almost all of his competitors are run by the state or state-run companies. “In essence, our own taxes are used by the government to finance several of them.”

Today, the outlet is doing more than just survive. Tied as the most-read Russian-language sports outlet with Championat.com — the parent company of which is a state-owned bank — Sports.ru attracts some 15 million visitors a month to its website and apps. It also has the highest amount of user-time for any media outlet in Russia, with people spending around 35 minutes on the site per visit, digging into blogs and comments, and writing their own.

In those forums, Sports.ru lets its readers speak their minds.

“It nearly became a problem in 2014 and 2015,” Navosha said, referring to the period after Russia annexed Crimea from Ukraine and backed separatists in its Donbass region. “You would have European-minded liberals and pro-government conservatives getting quite heated.”

For Navosha, though, such debates are just fine, even if they weren’t his initial intention for the site. He himself doesn’t shy away from staking out political positions: During the run of Russia’s most prominent opposition politician Alexei Navalny for Moscow mayor in 2013, Navosha supported him publicly.

“It’s not so much about the person as the principles of political competition in the country,” he said in an interview at the time.

In the current political moment, Sports.ru likewise did not hold back.

Alexander Aksyonov, the outlet’s editor-in-chief and creator of its merchandise collection, said the idea for the collection first came to him when OMON beat FC Spartak Moscow fans with batons during a July 20 away match in the southern city of Rostov-on-Don. But it also takes a strong position on the summer’s main events. In an official photo from the release, the model stands behind prison bars.

Navosha acknowledges that such moves could repel some of its audience, but he also notes that it has nonetheless been growing healthily over the years.

“It’s part of why our audience likes us,” Navosha said. “There’s a lot of fake media out there. Some have internal censorship; some produce propaganda. We offer candor.”

He said that the same principles are what have made Dud, who has 6.24 million subscribers to his YouTube channel, so popular. Dud, who helped build Sports.ru from the ground up, including as its editor-in-chief, left in late 2018 to focus on his own project, although he remains a minority shareholder in Sports.ru’s holding company Tribuna.com.

While Dud, who became persona non grata with the Russian state this summer after calling for his followers to attend the protests, has moved on, Saprykin noted that his principles remain. He pointed to the recent emergence of a younger version in the outlet’s star interviewer Alexander Golovin, who sat down with Navalny in June.

Asked if he worries such journalism may not appeal to the authorities, Navosha said he’s only ready to sacrifice his principles to a reasonable degree.

For years, he noted, Sports.ru didn’t register as an official media with state communications regulator Roskomnadzor because of his belief that media shouldn’t have to. But eventually that practice caught up with him. Sports.ru was denied approval to cover the Olympics when they came to Russia in 2014. And two years later, its content was blocked from Russia’s largest news aggregator Yandex’s “top news” lists, shrinking its audience.

So Sports.ru registered. Doing so, Navosha explained, didn’t force it into self-censorship — and anyway, he said, the outlet had faced pressure even before. A 2017 lawsuit by a state-run competitor, for instance, had been an attempt to kill Sports.ru’s operations, he said.

“OMON could be here tomorrow, putting everyone on the floor and taking hard disks,” he continued, referring to previous raids on independent media outlets. “It’s why we’re not complacent.”

That possibility is part of why Navosha decided to take a step back from Sports.ru earlier this year. Now, his focus is fully on Tribuna.com, a sports media project in six languages — Arabic, English, French, German, Italian, Spanish — and Navosha’s consideration of the bigger picture.

“We asked ourselves for a long time if we wanted to try expanding into the West and other countries, but we were scared of leaving our comfort zone,” he said. “We’ve since understood that not doing anything is even more frightening.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.