In 1881 the Russian writer Nikolai Leskov wrote a short story called “The Tale of Cross-Eyed Lefty and the Steel Flea” about a group of blacksmiths in Tula led by a left-handed master. In the story, Tsar Alexander I brought back a miniature mechanical flea made of steel from England. His son, Tsar Nicholas I, wants to find some Russian craftsmen who can outdo the English. A group of gunsmiths in Tula take on the challenge. After many months, the artisans hand back the same English steel flea, now broken. But under a microscope the tsar sees that Lefty and his team have fitted the flea with the tiniest horseshoes, which now prevent him from dancing.

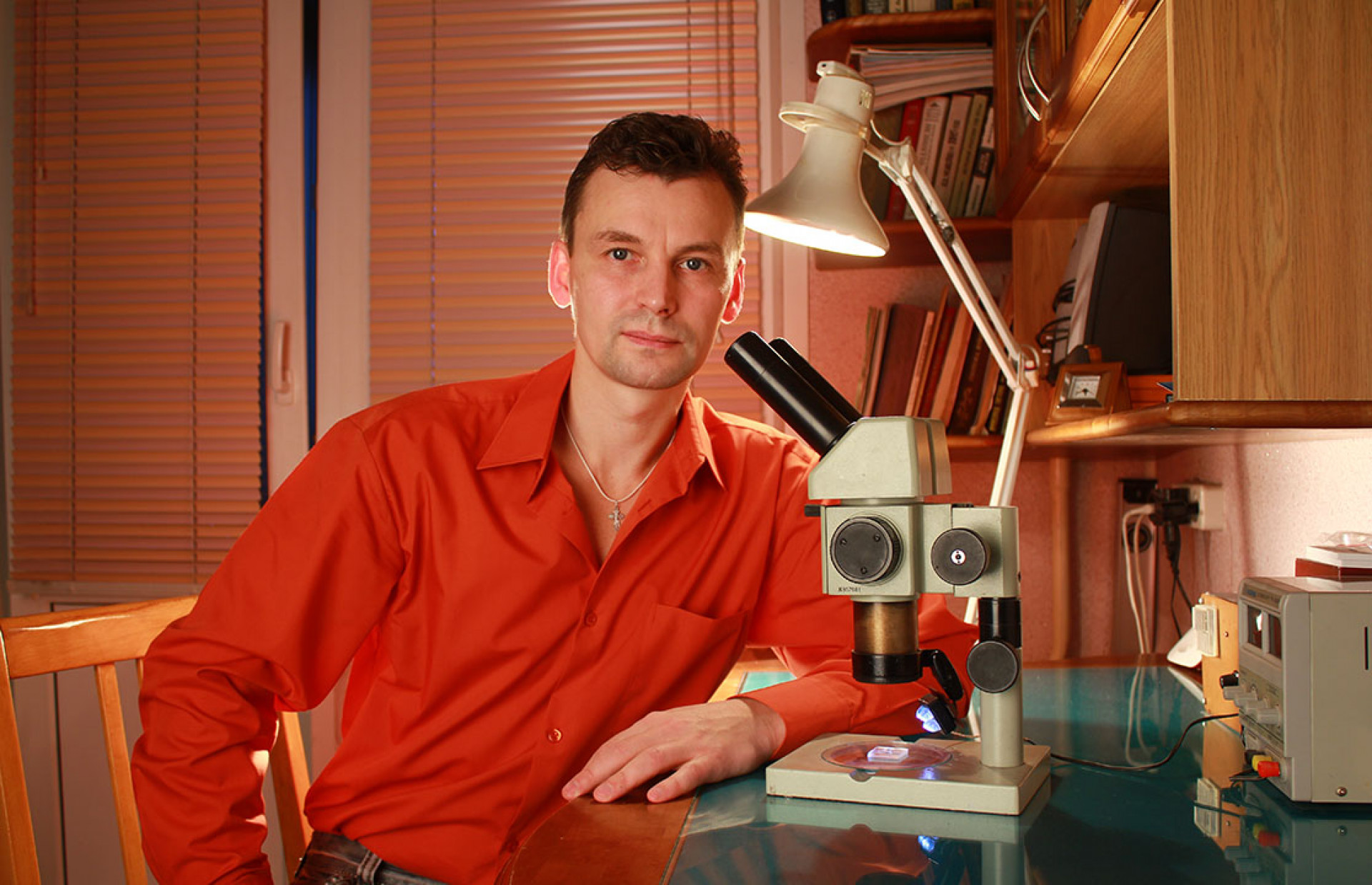

Today in Novosibirsk, a real-life craftsman is outdoing the fictional Lefty. Vladimir Aniskin makes artworks so tiny they are measured in microns and only visible through a powerful microscope.

The Novosibirsk micro-miniaturist studies microflows of liquids, gases and heat at the Institute of Theoretical and Applied Mechanics at the Siberian Branch of the Russian Academy of Sciences. He got interested in micro-miniatures in his last year at Novosibirsk State Technical University after reading the book “Secrets of Invisible Masterpieces” by Grigory Mishkevich. His first artwork was New Year's greetings to his mother on a rice seed in 1998.

Aniskin creates his amazing work in his free time and in absolute silence. Even the work of his heart disturbs such minute work, so particularly delicate work has to be done between heartbeats.

“I prefer working with three materials. First, I like gold because it is a noble metal and does not oxidize. Second, I like coloring pigment because it can be combined with plastic and I can create three-dimensional figures. Third, I like dust particles because they come in different colors,” Aniskin told The Moscow Times.

Aniskin began his exhibition career in Novosibirsk with a tribute to his fictional past master. Aniskin displayed two inscriptions made on a hair and a rice seed with pages from Leskov’s story, each with a golden horseshoe next to the first word.

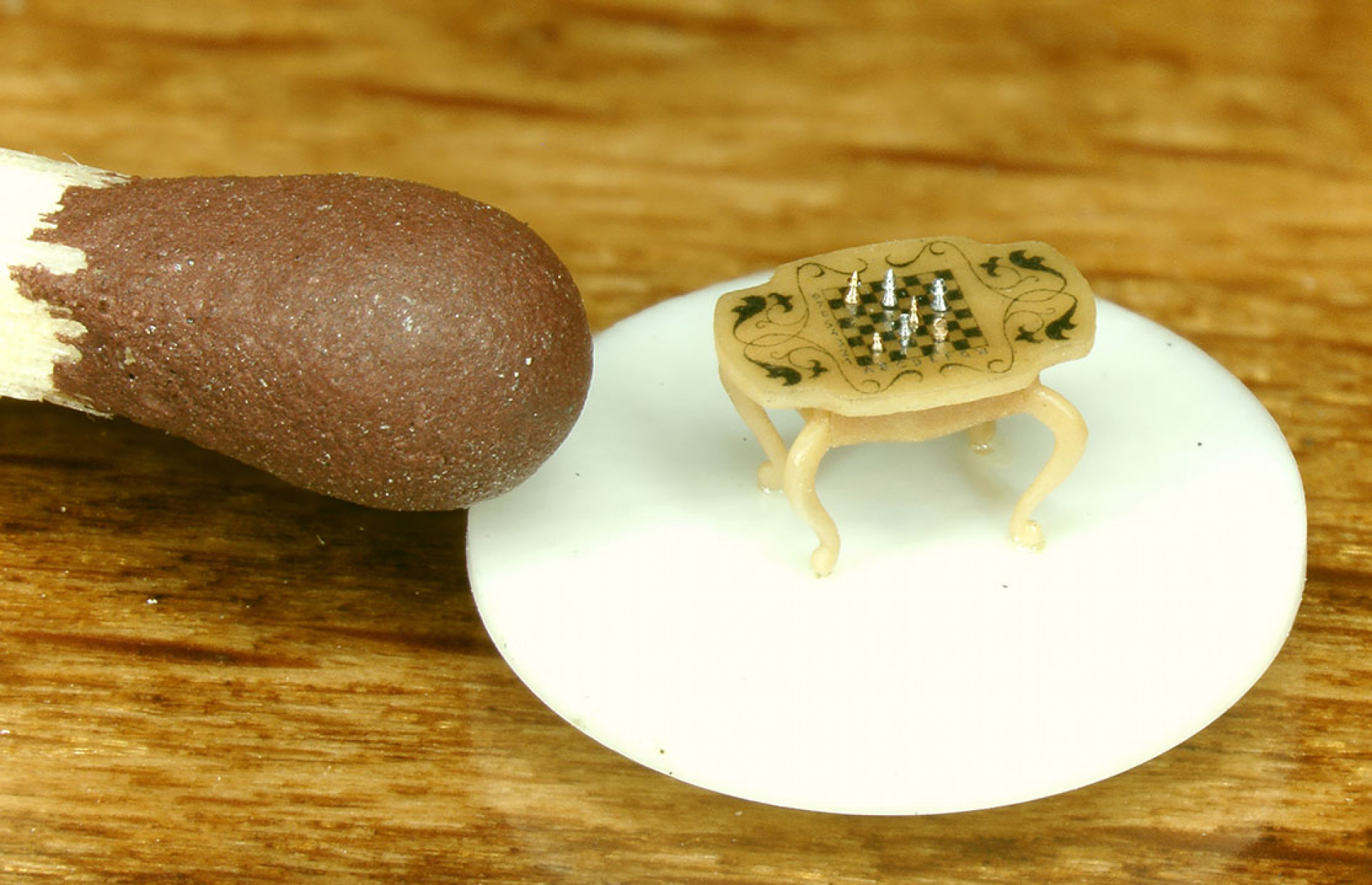

To make his works, Aniskin uses powerful microscopes and a set of tools he designed. Sometimes a piece will take a week to make, but a chess table out of a walnut took about six months and three attempts.

The world measured in microns

Aniskin has produced inscriptions on kernels of rice, a caravan of camels in the eye of a needle and even put horseshoes on a real flea. These are classic works for micro-miniaturists. Aniskin also creates three-dimensional figures and writes on hairs. The height of the letters is 0.15-0.20 millimeters; for comparison, the size of a red blood cell is about 0.07 millimeters. This work was extremely time-consuming since it was impossible to write more than three or four letters in a work session.

A few years ago Aniskin began to work with pencil lead and created hearts with the inscription “March 8” in honor of International Women's Day. There are almost no micro-miniaturists who work with pencil lead, since it is so fragile.

Recently Aniskin became interested in sand and began to collect varieties from different places. He plans to create a camel in the eye of a needle and decorate the artwork with sand from the Sahara Desert.

In and out of this world

Most of Aniskin’s works are in the Russian Lefty Museum of Miniatures in St. Petersburg. The museum exhibits his tiny copy the World Cup won by Zenit in 2008, a caravan of camels inside hollow horsehair, and many other works. Some works are in the Art Museum of Novosibirsk. A miniature copy of the icon of Nicholas the Wonderworker was presented by the master to the Orthodox church in Bari, Italy.

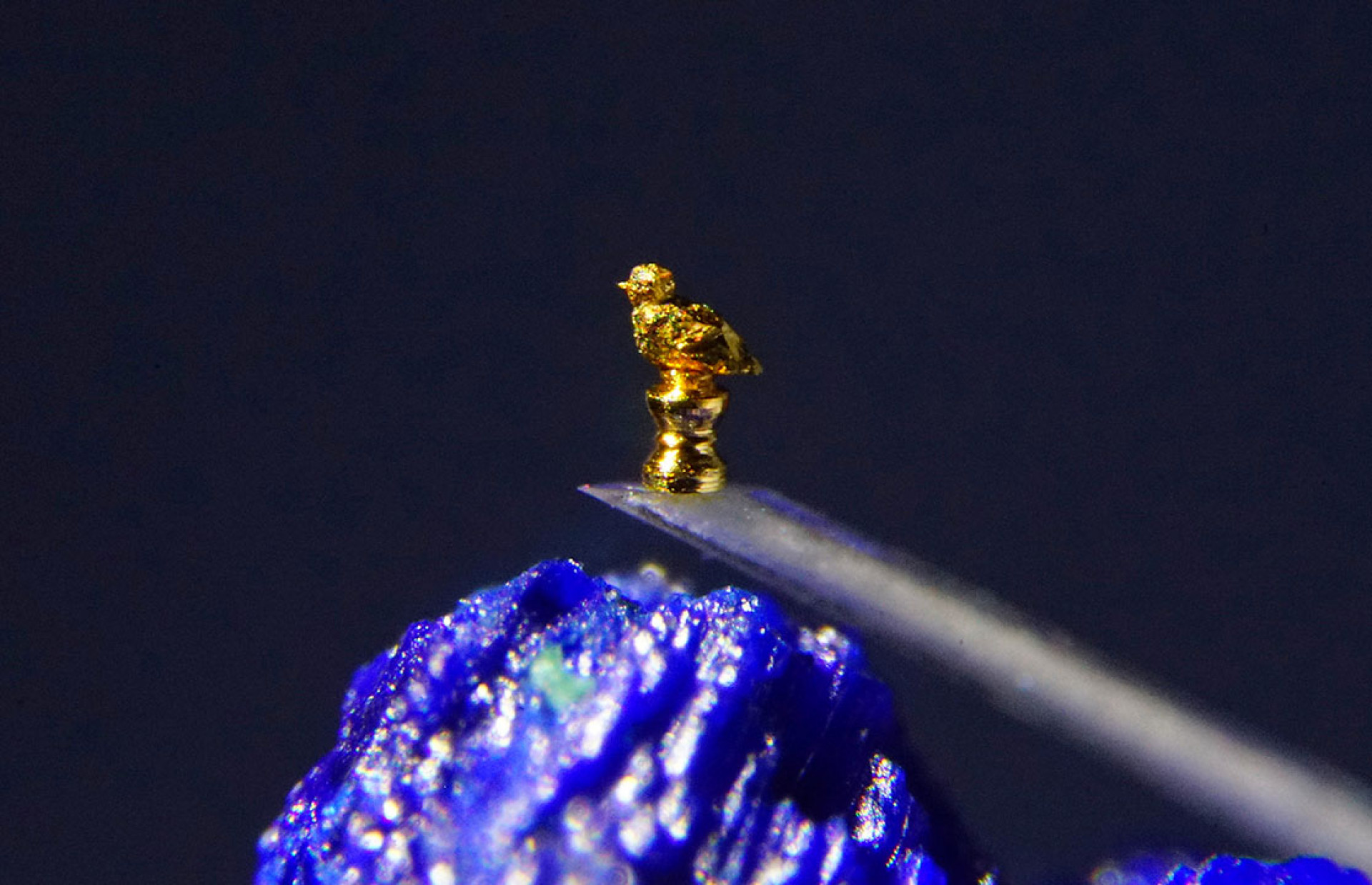

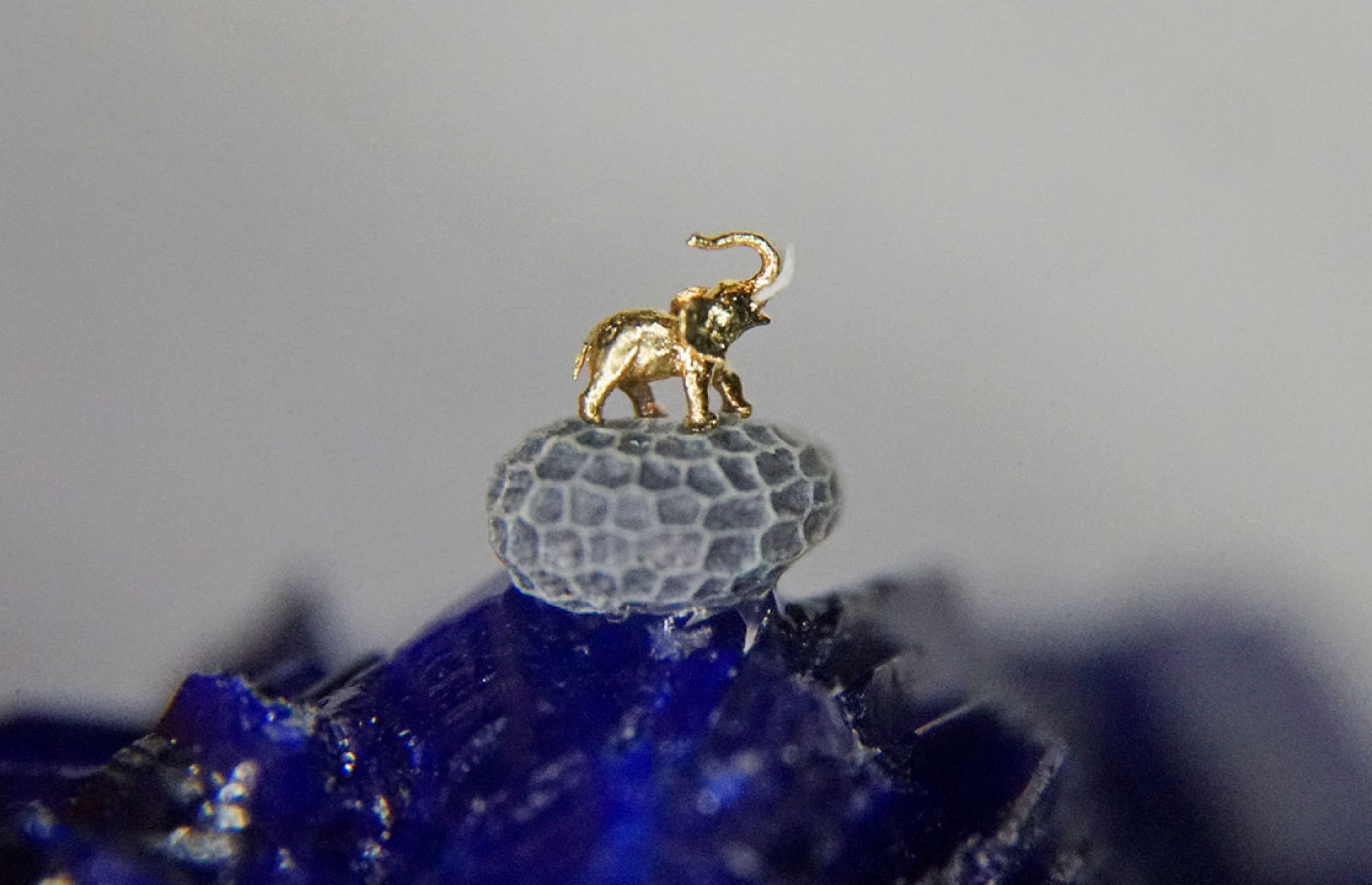

Three of his masterpieces are in the Russian Book of Records. The first one is the smallest sculpture of an animal. The elephant, 0.9 by 0.75 millimeters, stands on a poppy seed.

The second is the world’s smallest copy of a monument: the famous St. Petersburg monument Chizhik Pyzhik (a finch), mounted on a horsehair. The gold figure weighs 8 micrograms, and it is 0.2 millimeters high.

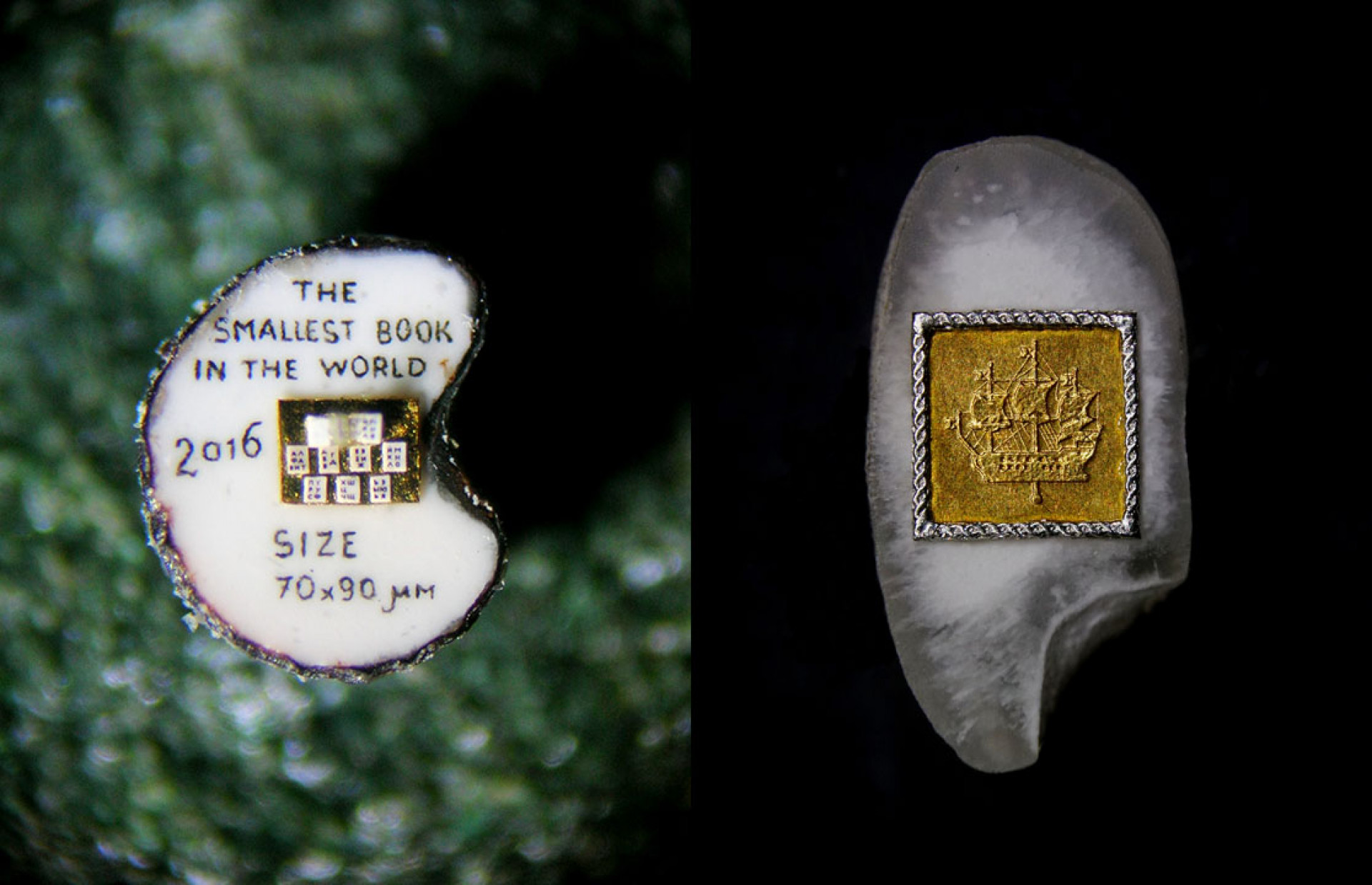

The third is the world’s smallest book, impossible to read with the naked eye. It measures 0.07 millimeters by 0.09 millimeters. Aniskin worked on it for a month. The book has two parts: the first, “Levsha,” contains the names of other micro-miniaturists, and the second, “Alphabet,” contains the Russian alphabet.

“Each page is coloring pigment covered with mylar. The letters are printed using photo-lithography. The most difficult part of the process was binding the pages together so they can be turned. I used wires with a diameter of 5 microns,” Aniskin explained.

Aniskin has commemorated military achievements with a painting of the Berlin monument to the Liberator Warrior on rice kernel. Recently he presented a portrait of the hero of the Soviet Union Alexander Demakov on an apple seed to the Novosibirsk Higher Military Command School.

Last year, his works went into outer space. Cosmonauts Alexander Lazutkin and Oleg Artemyev delivered a miniature ten-piece space museum to the International Space Station.

The space museum, which fits into the palm of your hand, includes a portrait of Yury Gagarin made of gold on a poppy seed, a watercolor portrait of the designer Sergey Korolyov, and an image of the space dogs Belka and Strelka on a sliver of apple. The tiny space museum arrived at the International Space Station on March 23, 2018 and circled the earth for 196 days. Today it is in the Gallery of Micro-Miniatures in Novosibirsk.

In 2019, artist Vladimir Aniskin was recognized as one of Novosibirsk’s most honored citizens.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.