It’s starting to look like a pattern: Russian law enforcement agencies arrest someone on what seem to be trumped-up charges; the arrestee’s colleagues raise their voices in protest; various pro-Kremlin figures join the outcry; the prisoner walks free.

This sequence of events first occurred in June, in the case of Ivan Golunov, an investigative reporter arrested on drug-dealing charges. Journalists who had worked with Golunov, myself included, could vouch that the charges were preposterous. We had a strong suspicion that Golunov was being punished for his investigation of corruption in the funeral business. So the Moscow journalistic community rose to the reporter’s defense, picketing police headquarters and trying to enlist the help of various officials. Three major newspapers, normally competitors, came out with identical front pages demanding freedom for Golunov.

Then, suddenly, pro-Kremlin figures, including Margarita Simonyan, the editor in chief of the RT channel, joined the campaign. President Vladimir Putin took a personal interest in the case, and Golunov was tested for contact with drugs and released, the charges against him dropped.

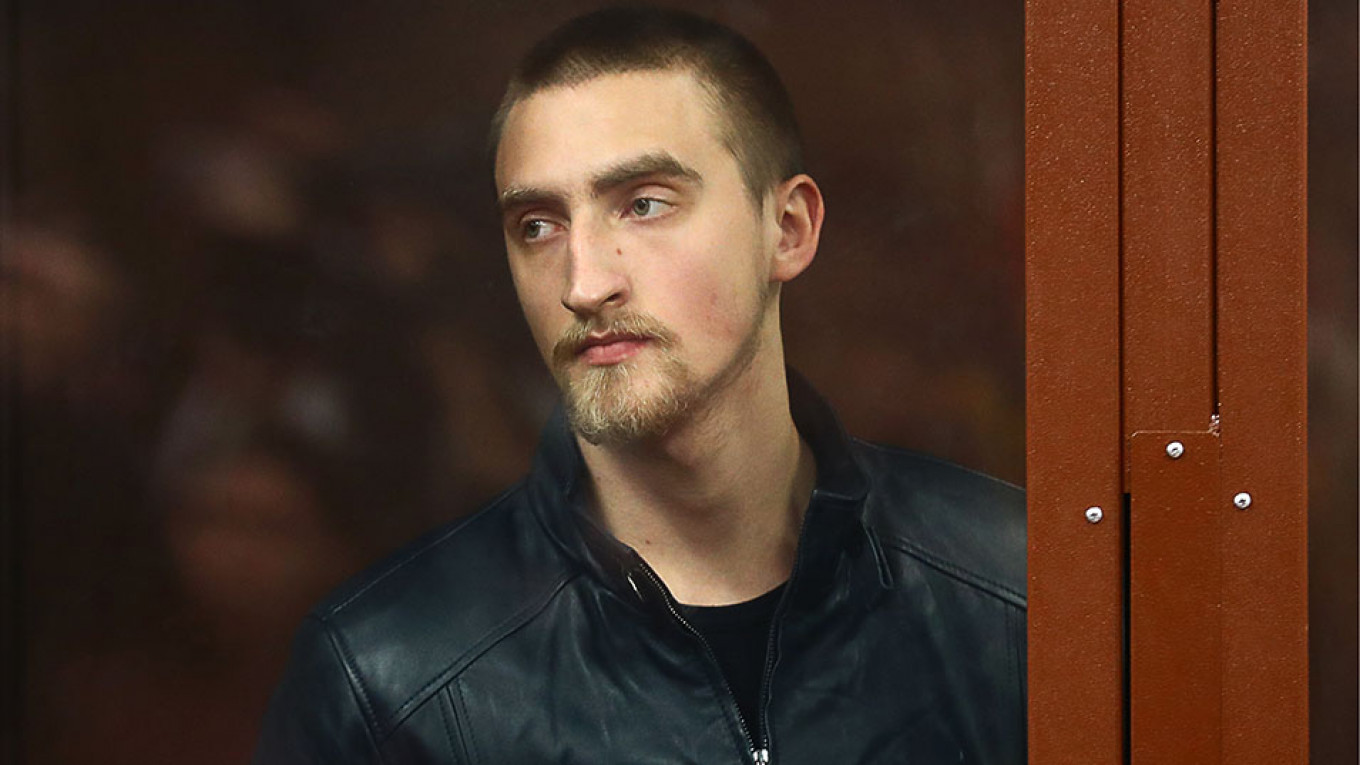

Now, it looks like a second iteration of the scheme is unfolding. On Aug. 3, Moscow riot police detained a young actor, Pavel Ustinov, during a protest against a city council election widely seen as unfair. Ustinov wasn’t taking part in the protest — he was just standing near a subway entrance in central Moscow, not far from where the demonstration was taking place. As the riot cops overpowered him, one ended up with a twisted shoulder. That resulted in Ustinov’s conviction on Sept. 16 for resisting arrest and a sentence of three years and six months in a prison camp — though a video, available on YouTube, shows clearly that he didn’t resist.

Actors showed as much solidarity for their colleague as journalists had before them. Theater and television stars spoke out in Ustinov’s defense, protests were held, a petition circulated. After a certain pause, just as in the Golunov case, Ustinov also found supporters among pro-Kremlin figures, from top television propagandist Vladimir Solovyov to Andrei Turchak, one of the leaders of the pro-Kremlin United Russia party. Two days after the sentencing, Turchak said the video of the actor’s detention, which the judge had ignored, proved Ustinov’s innocence.

Putin’s press secretary Dmitry Peskov said on Wednesday that Putin was aware of Ustinov’s case but couldn’t influence the court’s decision. But a top lawyer with Kremlin ties, Anatoly Kucherena, suddenly took up the case, and on Thursday, the Moscow prosecutor’s office asked the court to release Ustinov from prison.

Are the similarities between the Golunov and Ustinov cases a coincidence? Or is the Kremlin establishing a procedure for rolling back obviously unjustified reprisals by its overeager enforcers? Either way, Putin has signaled that complaints will quickly escalate to him if there’s enough public interest in the case — and if the victim has backers capable of generating and maintaining such public interest.

Like in the Soviet Union, it seems, certain privileged creative professionals, such as journalists and actors, are finding a sympathetic ear in the Kremlin. Victims of arbitrary reprisals who don’t have influential lobbies behind them — such as five other people convicted and sentenced to long prison terms for their part in last summer’s Moscow protests — are, it appears, not to be freed in this way. Public support from random social network users, activists or the 40 Russian Orthodox priests who authored an open letter advocating for detainees’ releases doesn’t seem to count.

The rules of the game are ad hoc, as rules often are in the Putin system. Putin knows, however, that Russian elites will play by whatever rules he implicitly sets — and thus, also implicitly, accept that some political prisoners must remain behind bars. That’s ultimately what he wants; if his sadistic enforcers often act irrationally, he’s using their brutality to make key professional communities play along with him.

This article first appeared in Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.