Russian President Vladimir Putin has a bee in his bonnet about debt. Having lived through the 1998 crisis when Russia’s financial system was wiped out for the want of a few billion dollars to meet the government’s obligations, there has been a strong “never again” meme that has run through the Kremlin’s financial policy.

Amongst the first things that Putin did when he came to power in 2000 was pay off all Russia’s debt to the International Monetary Fund (IMF) early and then shortly afterwards the so-called London and Paris Club debts left over from the Soviet Union days. During the boom years Putin signed off on former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin’s plan to ring fence several reserve funds that amazingly were kept away from greedy oligarchs and profligate Duma deputies.

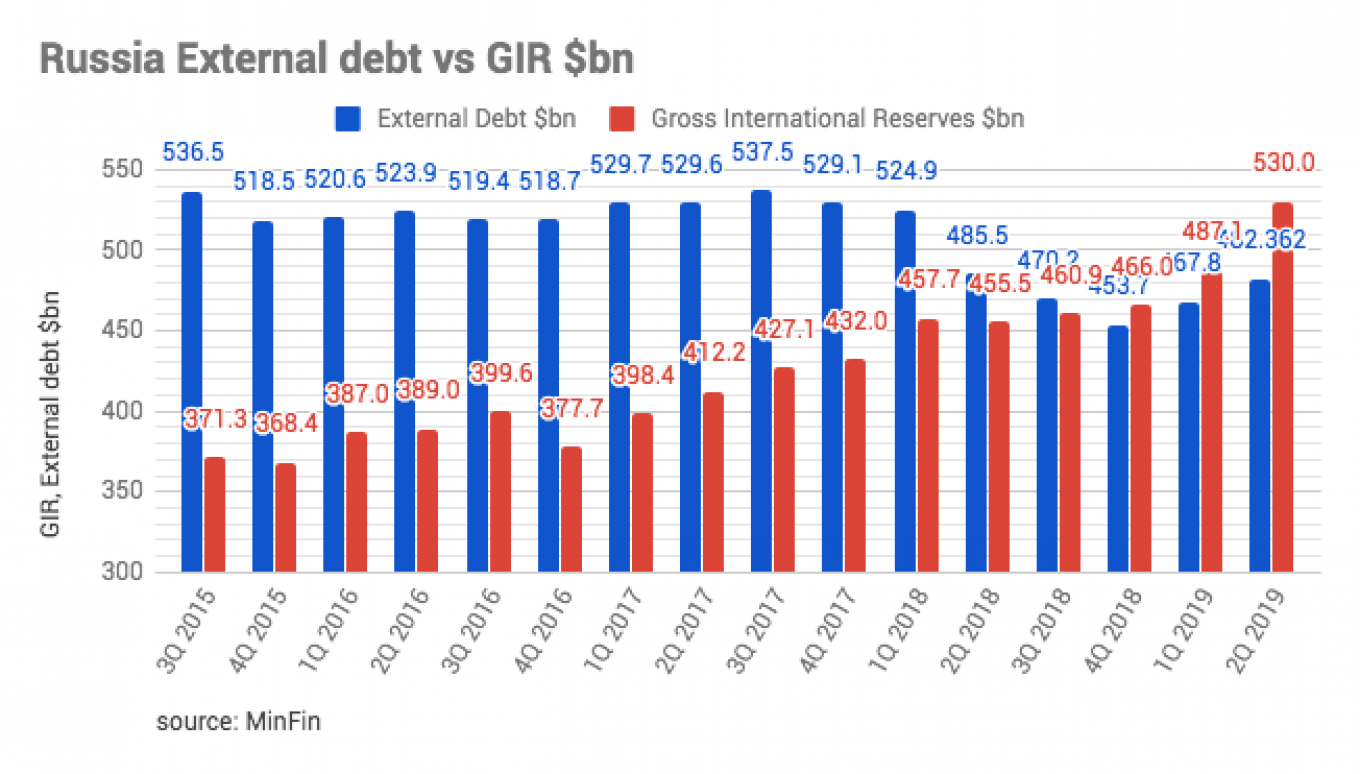

This February Putin crowed in his state of the nation speech that Russia’s cash reserves had grown so big the country can now cover its external debt dollar-for-dollar with cash as Russia’s gross international reserves (GIR) overtook the external debt for the first time ever.

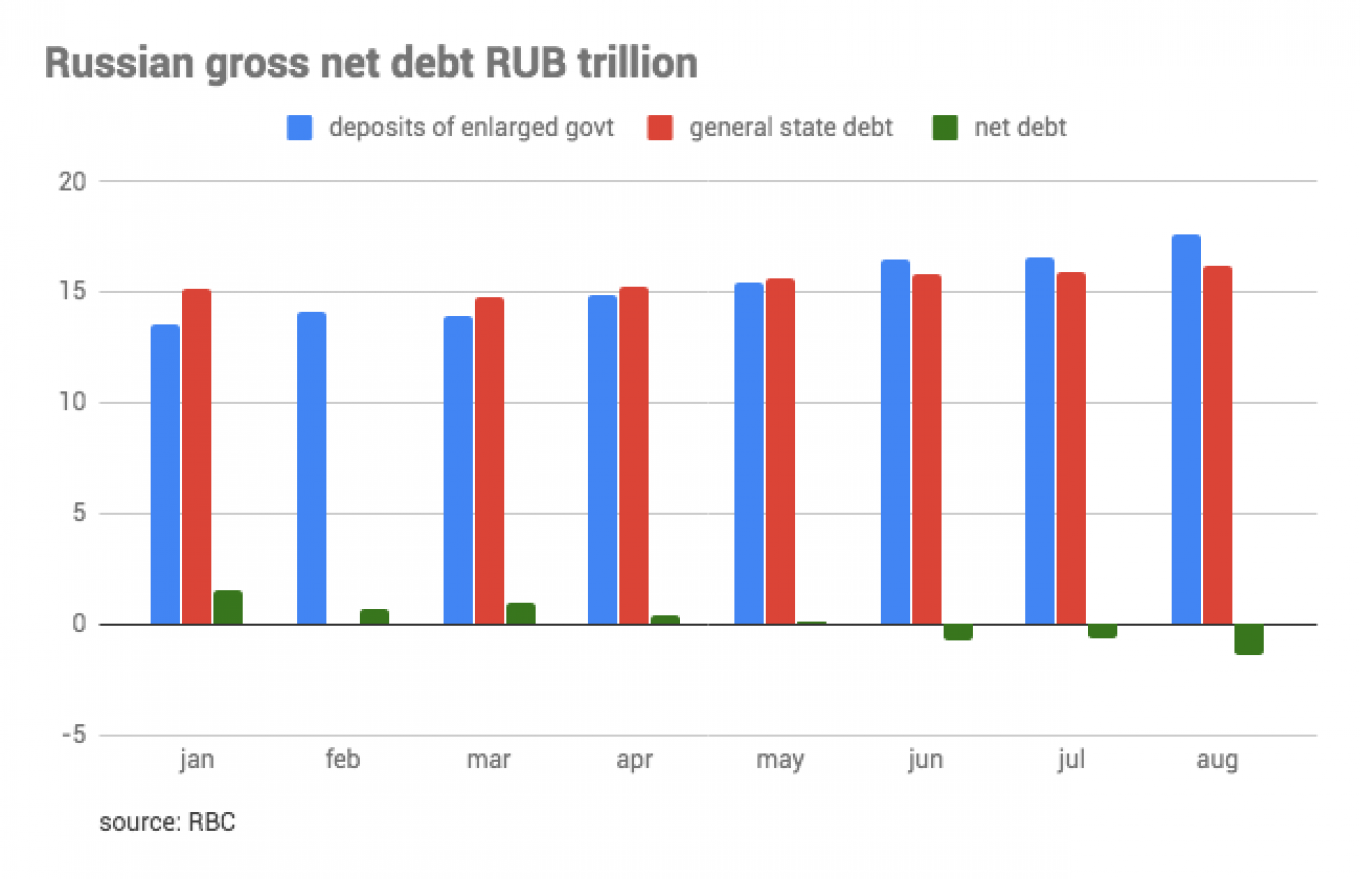

Now the country has gone to the next level. Russia’s net public debt has fallen to zero for the first time since the introduction of sanctions and the collapse of oil prices, reports RBC.

Public debt is the broadest definition of debt and includes the more narrowly defined external debt, as well as the domestic debts of the government, the regions and the municipalities. As of Aug. 1 the total state debt was 16.2 trillion rubles ($248 billion) or 15% of GDP and equivalent to what the government takes in each year in total as taxes. The amount the state has in cash in deposits with the Central Bank was 17.6 trillion rubles ($269 billion) on the same date, or 16.2% of GDP.

“In other words, if Russia suddenly needed to pay off all its debts immediately, it could do it just by dipping into the cash on account at the government deposits with the Central Bank and commercial banks,” writes Ivan Tkachev, the economics editor at RBC.

Although oil prices are much lower than their boom years peak of some $150, Russia Inc is accumulating money quickly again as it has become a lot more profitable than it was in the noughties. In the noughties the breakeven price of oil for the budget was $115 per barrel but now that has fallen to around $41, so while the prices are lower Russia’s profit margin is wider.

The gross international reserves increased sharply in 2018 and are likely to increase at the same pace this year, reports RBC. The volume of cash currency and cash on deposits in the general government accounts in 2018 grew by a record 3.87 trillion rubles ($59 billion), according to Rosstat data on national accounts — an all time record gain in a single year.

But Russia’s campaign to drive down debt has come at a cost. The austerity that comes with not leveraging up the country's economic potential and borrowing a bit more carries the price of slow growth, say analysts. Russia could have increased its total debt by half without threatening financial stability and used the extra money to boost growth and end the stagnation, according to analysts at Sberbank CIB, but won’t as long as it is in a de facto economic war with the US.

Russia’s uniquely low net debt

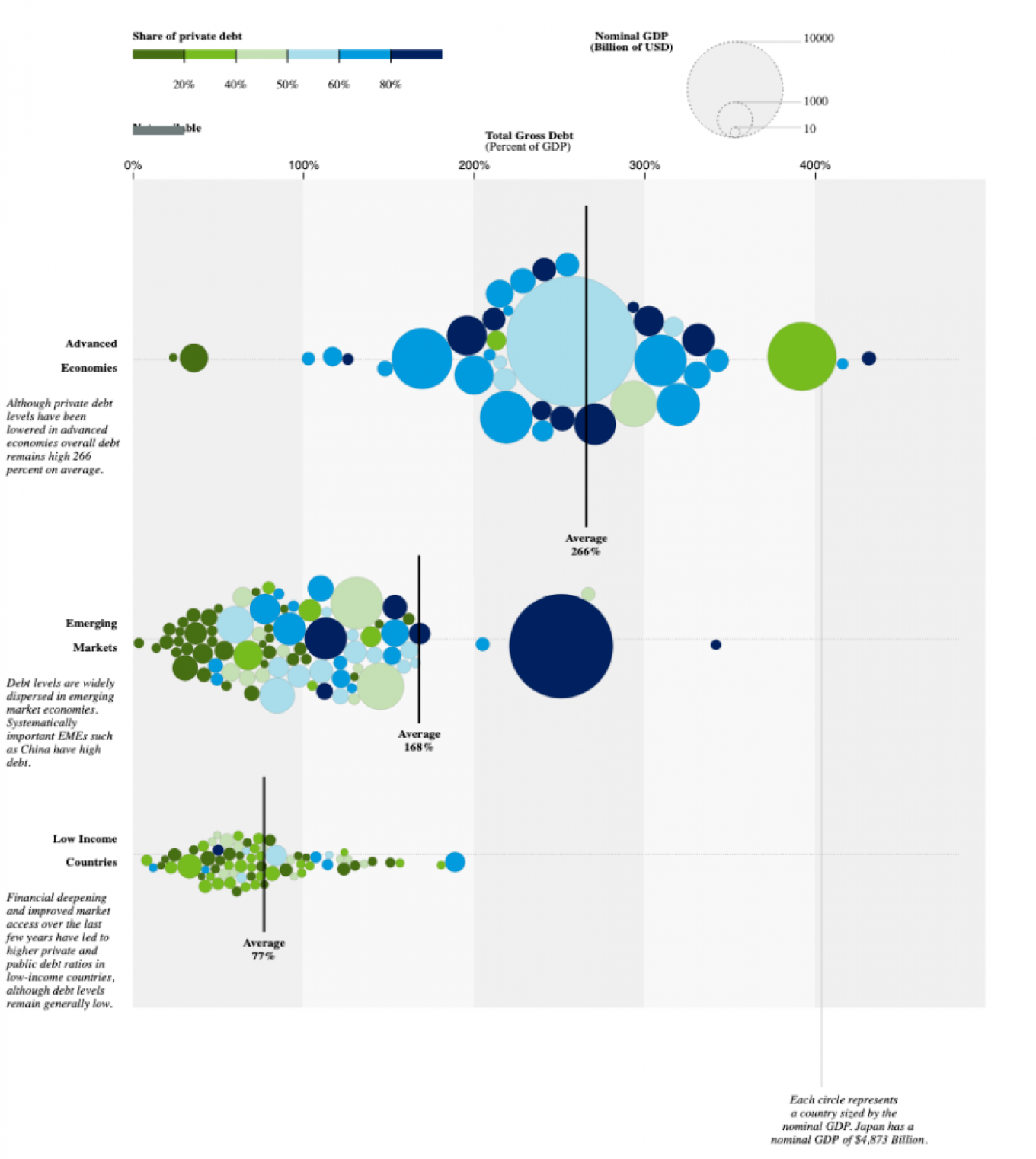

Russia’s zero net public debt makes it unique amongst the major economies of the world, but it is not debt free and this does not include the commercial debt, which in Russia’s case makes up eight out of every ten dollars of its total gross debt.

However, even including the commercial debt into the calculation, Russia still comes out way ahead of the rest of the world. Most countries ran up huge bills as they borrowed heavily to stave off recession following the 2008 global financial crisis, caused by the implosion of the US sub-prime mortgage market and its mortgage backed securities.

Developed world economies are running total gross debt to GDP ratios of around 200% of GDP or more and global gross debt is currently at a record high. Total global gross debt topped $184 billion at the end of 2017, or 225% of global GDP, according to the IMF.

In per capita terms that is $86,000 of debt per person on the planet, or the equivalent of two and a half times the average annual income of all the people in the world on average. In Russia there is a mere $900 of gross total debt per capita, or slightly more than the equivalent of one month’s salary.

While Russia’s total public debt is around 15% of GDP its total gross debt is 84% of GDP of which 81% is privately owned debt, according to the IMF. The difference is that while developed markets, with their sophisticated financial sectors, maintain only small international foreign exchange reserves, as they can finance imports using financial instruments, the emerging markets tend to keep at least three months of reserves on account as a buffer against external shocks. In Russia’s case these reserves topped $500 billion earlier this year for the first time since the Crimean sanctions were imposed, which is enough to pay for 13.5 months of imports — vastly in excess of what economists believe is needed to ensure the stability of the national currency.

For comparison the U.S. is now one of the biggest debtors in the world, both in nominal and relative terms with a gross debt (private and public) equivalent to 256% of GDP of which 58% is privately owned, according to the IMF. As the chart shows, all of the developed markets have significantly higher debt than the emerging markets, with Japan as the outlier with almost 400% of GDP of total debt.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.