Over the weekend of Aug. 10, when Russian riot police beat and arrested peaceful protesters in Moscow, another type of assault was being prepared in the northwestern republic of Karelia. The Russian Military-Historical Society (RMHS) was about to start its second illegal excavation of mass graves of the victims of Stalinist repressions in the forest of Sandormokh.

The official aim of the unauthorized work, which began on Aug. 12, is to uncover the remains of Soviet POWs executed by the Finnish army during the Second World War. But its ultimate goal is to obfuscate and diminish Sandormokh’s significance as a memorial to the victims — and a testament to the crimes — of the Soviet regime.

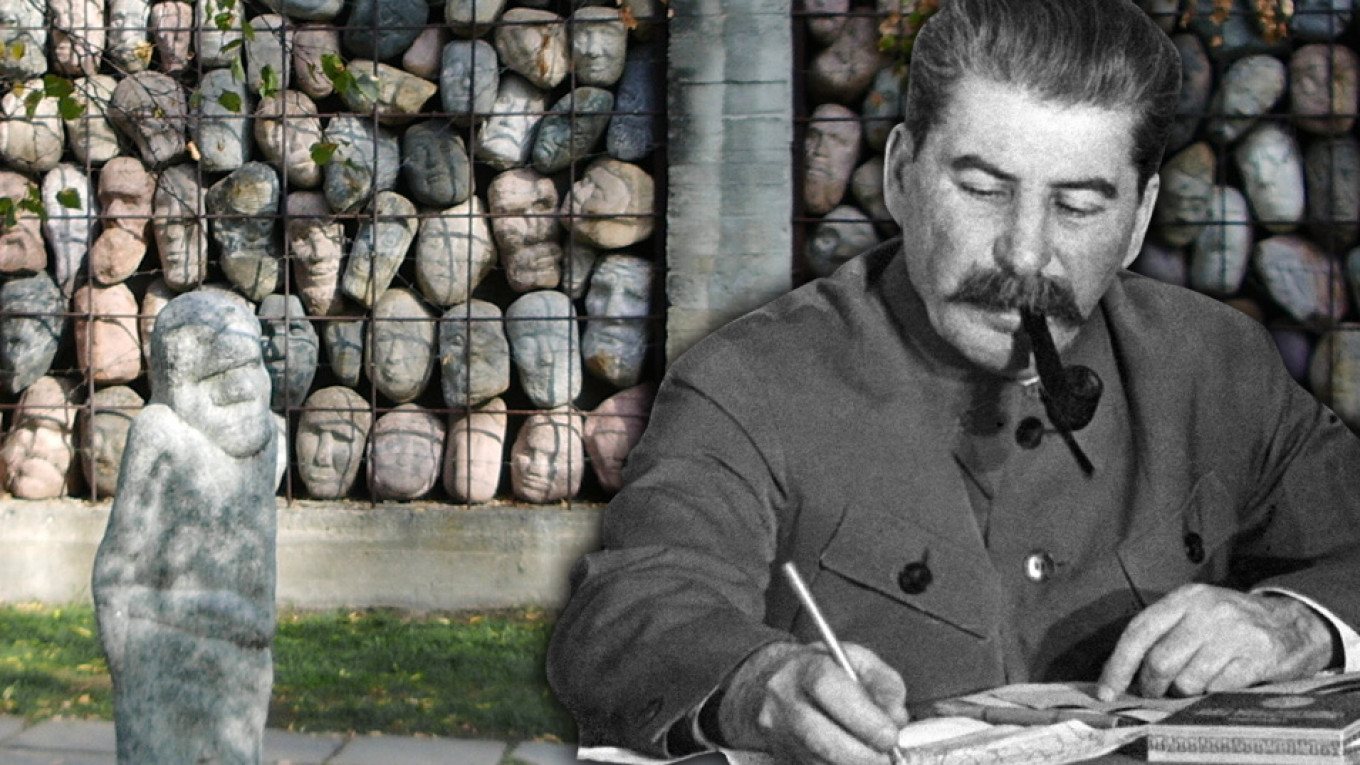

Since 1997, a team of researchers from Russia’s oldest human rights organization Memorial, led by the chairman of its Karelian branch, historian and social activist Yuri Dmitriev, have identified over 230 mass graves containing the remains of victims of the Great Terror. Since then, Sandormokh has become a shrine to the victims of Stalin’s crimes, hosting an annual International Day of Remembrance on Aug. 5.

In 2000, the site received special state protection as a “historical memorial,” a status that prohibited any groundwork without special permission from the authorities.

Things changed in 2016. Several historians from Petrozavodsk State University, led by former military historian Sergei Verigin, claimed that Sandormokh might contain the remains of hundreds of executed Soviet POWs buried there by the Finnish armed forces between 1942 and 1944.

These claims were not substantiated by any scientific proof, unlike the meticulous evidentiary base of Stalinist repressions constructed by Memorial and other NGOs that documented the names of 6,241 individuals executed in Sandormokh by the NKVD between 1937 and 1938.

The authorities nevertheless seized on the unlikely hypothesis, employing all available means at their disposal to discredit over 20 years of scientific work. For the first time since 1998, none of the representatives of Karelian authorities attended the Aug, 5 commemorative events. More recently, the local government demanded the recategorization of Sandormokh to a place of “cultural significance.” Though the request was denied, a new classification would have eased permit requirements.

On December 13, 2016, Dmitriev — who was also a member of the local commission for the rehabilitation of victims of political repressions and had campaigned against the RMHS excavations — was arrested on child pornography charges based on an anonymous statement from an FSB official. He was acquitted in April 2018, only to be rearrested in June 2018 on charges of sexual abuse. He is a political prisoner whose ongoing trial, it is widely believed, is based on fabricated evidence.

Sergei Koltyrin, the director of the Medvezhyegorsk District Museum who had administered the Sandormokh site and collaborated with Dmitriev and other Memorial researchers, was arrested on charges of pedophilia in 2018 and sentenced to nine years in prison earlier this year. He had publicly expressed his fears that he would suffer the same fate as Dmitriev.

In Aug. 2018, without obtaining the necessary authorizations, the RMHS launched its first mission to look for the remains of Soviet POWs in Sandormokh. Its findings, including a piece of cloth which was subsequently discarded and bullet casings from a gun commonly employed by NKVD, did not reveal a single piece of reliable evidence to advance Verigin’s hypothesis.

The boycotts of commemorations, arrests of historians opposed to excavations, requests to change status and desecration of mass graves at Sandormokh are all part of a concerted campaign to shift emphasis from the memorialization of victims of Stalinist repressions to that of Soviet POWs. This directive is coming from the top, as Russia seeks to forge its identity around the glorification of the principal Soviet achievement — victory in the Second World War.

Since coming to power, former Soviet KGB officer Vladimir Putin has looked to the Soviet era for positive historic material to restore Russia’s pride, patriotism, stability and global influence. He has seized on the catalyzing potential of Soviet victory and sacrifice in the Second World War to perpetuate the narrative of a strong Russian state and justify an increasingly centralized form of governance, the dominance of power structures and an expansionist stance in foreign policy.

Any foreign or domestic efforts that might undermine the sanctity of victory in the Second World War are interpreted as assaults on Russia’s new identity and warrant a forceful response.

Indeed, the very raison d’etre of the RMHS, established by presidential decree in 2012, is “to consolidate the forces of the state and society in … countering attempts at distortion, ensure the popularization of the achievements of military-historical science, raising the prestige of military service and patriotic education.”

In 2007, Russia became embroiled in a conflict with Estonia over the removal of a memorial to Soviet soldiers from the center of Tallinn to a war cemetery, which the Russian authorities and media interpreted as an open manifestation of fascism and an anti-Russian act.

In March 2014, Putin employed anti-fascist rhetoric and historical memory to justify the annexation of Crimea. Shortly thereafter, an amendment to Article 354.1 of the Criminal Code prohibited the rehabilitation of Nazism by outlawing the dissemination of any knowingly false information regarding the U.S.S.R.’s actions during the Second World War.

In 2016, Russia’s Supreme Court upheld the conviction of a Perm resident for having publicly claimed that the Soviets actively collaborated with Nazi Germany in dividing Poland according to the Molotov-Ribbentrop Pact, which is historically accurate.

Because Sandormokh contained the remains of victims of Ukrainian, Polish, Lithuanian and other descent, and constituted one of the few laudable efforts by Russia’s civil society to acknowledge the repressive Soviet past, the annual commemoration attracted both local and international attention, becoming a thorn in the side of the Russian authorities.

This is proved by a July 2019 letter from Karelia’s Culture Ministry to the RMHS, urging a second excavation. In it, the local authorities dispute Memorial’s findings, complaining that the “idea” of a burial site for victims of political repressions “is used by certain countries for destructive informational-propagandist reasons in the sphere of historical memory.”

They also argue that “speculation about the events in Sandormakh not only causes harm to Russia’s international image, but also cements in the collective conscience of citizens an unjustified feeling of guilt concerning the allegedly repressed representatives of foreign nations, allows for the advancement of baseless claims against our nation, and becomes a consolidating factor for anti-government powers in Russia.”

The unlikely discovery of Soviet POWs in Sandorkmokh during these excavations would bolster the state’s historical narrative. However, these efforts already constitute a blatant attempt to whitewash the repressive Soviet past and deliberately destroy cultural heritage.

They also contravene Russia’s international commitments, such as those embodied in the Oct. 17 2003 UNESCO Declaration on the Intentional Destruction of Cultural Heritage, which requires Russia to take all appropriate measures to prevent, avoid, stop and suppress acts of intentional destruction of cultural heritage, and to disclose the full truth about the predecessor regime’s crimes.

The real harm to Russia’s image stems not from the tireless work of civil society and political prisoners like Yuri Dmitriev in uncovering the truth about Soviet crimes, but from the attempts of the RSMH and other authorities to trample on their efforts.

Those actions insult the memory of the thousands of Russians and non-Russians who perished at the hands of Stalinist executioners.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.