As Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskiy consolidates power after his party gained a majority in parliament, there’s a sense in Europe that conditions might be ripe for productive talks on resolving the festering conflict in eastern Ukraine. French President Emmanuel Macron says there’ll be a France-Germany-Ukraine-Russia summit on the subject next month, the first since 2016. Meanwhile, John Bolton, national security adviser to U.S. President Donald Trump, is asking Zelenskiy to take his time: the Europeans may not “have a solution that is readily apparent.”

As ever, the Europeans want the war to end on any terms acceptable to the parties, and the Americans are worried about any possible concessions to Russia. But all this activity around a possible resolution goes right over the heads of the most important stakeholders: The people of eastern Ukraine who live on both sides of the front line — a total of about 6.2 million people, of which about 3.7 million are in the so-called Donetsk and Luhansk People’s Republics, the DNR and LNR respectively.

The Berlin-based Center for East European and International Studies (ZOiS) has just published a report on how sentiment in both Ukrainian and separatist-controlled parts of eastern Ukraine has evolved in the last three years — coincidentally, the period without “Normandy format” meetings like the one Macron has announced. The report is based on in-person interviews with 1,200 residents of the Kiev-controlled part of the Donetsk and Luhansk regions and telephone interviews with 1,200 people in the unrecognized “people’s republics” kept alive by Russian support. In that, the survey is unique — few researchers dare conduct any kind of field work in the DNR and LNR.

The results show a remarkable diversity of opinion, but they indicate a path toward a reasonable settlement that all parties should aim to follow.

The first, most striking result of this survey is that on both sides of the border, “Ukrainian citizen” isn’t the primary self-identification. In the Kiev-controlled areas, only 26% of respondents identified primarily as Ukrainian citizens, down from 53% in 2016. But then, the “people’s republics” don’t inspire much enthusiasm, either. No identity dominates on either side of the separation line.

That’s an important finding. The lack of a strong affiliation with Russia, Ukraine or even the home region, the Donbass, means, on the one hand, that none of the major players in the conflict have managed to offer anything attractive to the population. On the other hand, it shows that there should be a lot of flexibility in resolving the conflict — and not much entrenched, identity-based resistance of the kind one finds in the Balkans.

Another important positive finding for Ukraine is that people in the “people’s republics” have been crossing the line into the Kiev-controlled part of the country more often than in 2016: The percentage who do it once a month, for example, has increased to 14.8% from 7.9%. Residents of the Ukrainian-controlled part almost never travel to the DNR and LNR; a higher percentage of people in the separatist areas say they have friends and relatives across the line than the other way round.

The direction and frequency of the traffic means the separatist experiment hasn’t succeeded in cutting off parts of the Donbass, even though almost 56% of the “people’s republics’” residents still say they never cross the line.

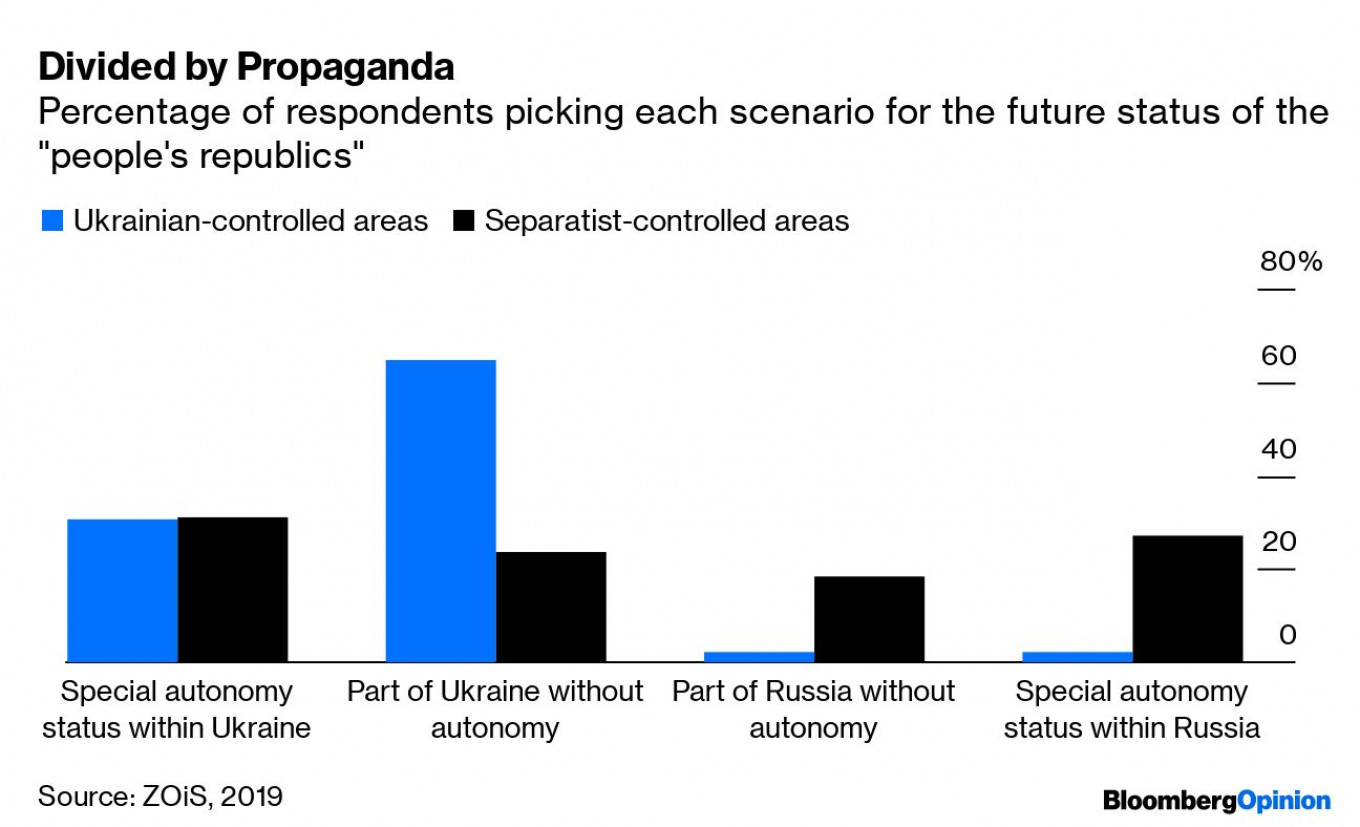

The two parts of the Donbass have been subjected to conflicting propaganda streams since the war started, and their ideas about the region’s future have diverged accordingly. In the Kiev-controlled parts, even though they voted for the pro-Russian opposition in this year’s elections, about two thirds of residents believe the “people’s republics” should rejoin Ukraine without any special status, and that proportion hasn’t changed much since 2016. In the DNR and LNR, only about a quarter agree — slightly more than in 2016, indicating that some people are tired of the uncertainty. At the same time, the share of those who want their region to become part of Russia also has increased, to 18.3% from 11.4%, another sign people want the conflict to end one way or another.

And yet these differences don’t present a particularly daunting challenge to Ukraine. People in the separatist areas haven’t acquired a belief in their separate statehood, and only a minority wants them to join Russia. Autonomy or not, the people’s republics have a pro-Ukrainian majority, if the ZOiS survey is accurate.

Based on the German think tank’s findings, Zelenskiy’s strategy in any negotiations going forward should be to insist on a popular vote, ideally in both parts of eastern Ukraine, arranged and observed by a credible international organization, such as the United Nations or the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe. Based on the ZOiS findings and the population distribution between the Kiev-controlled and the separatist-held areas, such a referendum should return a plurality (about 40%) for the region’s reunification within Ukraine without any special autonomous status; the second most popular result (with about 31%) would be autonomy within Ukraine.

That latter option wouldn’t necessarily win in a run-off either, depending on what kind of economic revival package Ukraine and its Western allies would be able to offer the people of the Donbass. Russia won’t be offering any such package, at least not credibly. It’s had its chance to pump the rebel republics full of infrastructure investment, as it did with Crimea, but the Kremlin decided against it.

Even if a vote were held in the separatist areas only, an international effort to secure it and allow Zelenskiy to campaign there (his prowess at it is well-known by now) could end in Ukraine’s favor, without the need to change the constitution to give the Donbass a special status. But even a vote for an autonomous status wouldn’t be the end of the world. It would merely set the stage for more detailed negotiations on what autonomy should entail and exactly what constitutional change would be needed.

Russian President Vladimir Putin’s entire rhetoric since the conflict in eastern Ukraine began has been about protecting the country’s Russian-speaking minority and, specifically, the residents of the “people’s republics.” Insistence on a fair, internationally recognized vote would defang that rhetoric and give Putin an honorable way out of the expensive mess. The Kremlin would, of course, bargain, put forward impossible conditions, demand security guarantees for its most active supporters and insist on autonomy for the Donbass as a condition of any progress. But a compromise could be reachable with an amnesty for all combatants.

After five years of war and more than 13,000 deaths, it’s finally time to ask the people of eastern Ukraine how they’d like to proceed. The ZOiS findings show they’ll probably make a reasonable decision. Germany, France and the U.S. should help Ukraine and Russia agree on a democratic solution to the crisis.

This article originally appeared in Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.