The Atlantic Council, the venerable U.S. think tank, recently released a report on the latest wave of Russian emigration, which it calls the “Putin Exodus.” As an emigre, I usually welcome this kind of research, but this study has reached the wrong conclusions.

The report, by retired U.S. Ambassador John Herbst and Sergei Erofeev of Rutgers University, makes a novel and important point about the most recent Russian emigres. “There is a distinct disparity between those who emigrated before 2012 and those who left later: among other things, the latter demonstrate a growing pro-Western and liberal orientation and greater politicization in general, including stronger support for the anti-Putin ‘non-systemic’ opposition.”

It’s true that 2012 was a turning point for some of my peers in Russia. Vladimir Putin returned to the presidency after Dmitry Medvedev kept the seat warm for him while initiating what was perceived by some intellectuals as something of a thaw. Putin, however, tightened the screws, restricting media, political and academic freedoms. Then, in 2014, he annexed Crimea from Ukraine. The report suggests the post-2012 emigration is different, more politically motivated. For that reason, the authors say Western policy makers should court this wave of Russian newcomers, seeking allies among it and welcoming it more than the previous ones. “The emigration can be a bridge between the West and a Russia that is not destined to be authoritarian,” Herbst and Erofeev wrote.

The conclusions and policy recommendations are backed by a survey of Russian emigres living in London, Berlin and environs, New York and Silicon Valley, 100 in each location. All 400 had left Russia since 2000. Some responded to Atlantic Council’s open invitations on social networks and others were recruited through a “snowball sample” approach — that is, they were invited by the other participants or approached through their social network contacts. Some of the respondents later took part in focus groups.

According to the survey results, the “Putin Exodus” is more liberal than the generally conservative pre-2000 emigration waves. Most would like Russia to pursue a pro-Western European path. Most are pessimistic about Russia’s future, which would explain why only about a third would be willing to support the Russian opposition, though even that is pretty high compared with previous groups of emigres. Support for Putin is tiny.

The survey showed major differences between pre-2012 and post-2012 emigres. Twice as many respondents in the later cohort say they left because of the “general political climate” or the “lack of political rights and freedoms.” Fewer of the later immigrants left to pursue educational opportunities. The post-2012 part of the “Putin Exodus,” then, is relatively politicized. A bigger part of the post-2012 cohort would consider going back to Russia if the political climate improves.

The Atlantic Council puts the size of the post-2000 Putin Exodus at 1.6 million to 2 million. If that estimate were correct and if the survey accurately represents the views of this large number of Russian emigres, it would mean there’s a sizable Russian population in Western countries interested in helping Western politicians push Russia toward a liberal path, including with sanctions (52 percent of the Atlantic Council’s sample backed them).

Our family left Russia in 2014; the Crimea annexation was the direct reason, though increasing media censorship also played a role. I’m even quoted in the Atlantic Council report: Immediately before leaving my native Moscow, I wrote a post calling the new departures “the emigration of disappointment.” But I have a problem with the report’s findings that’s best described by the saying, “From your mouth to God’s ears.”

The report’s authors acknowledged that their sample might not be representative of the latest emigration wave (36 percent of respondents had a graduate degree and 65 percent came from Moscow and St. Petersburg). That’s probably an understatement. Some of the respondents were solicited through social network invitations, resulting in several layers of self-selection that would have rendered the sample useless for a peer-reviewed study. A more workable — but certainly expensive and time-consuming — study design would have included recruitment in real-world Russian community institutions such as bilingual schools, clubs and restaurants frequented by the community, Russian businesses with large emigre client bases.

The report’s authors acknowledged that their sample might not be representative of the latest emigration wave.

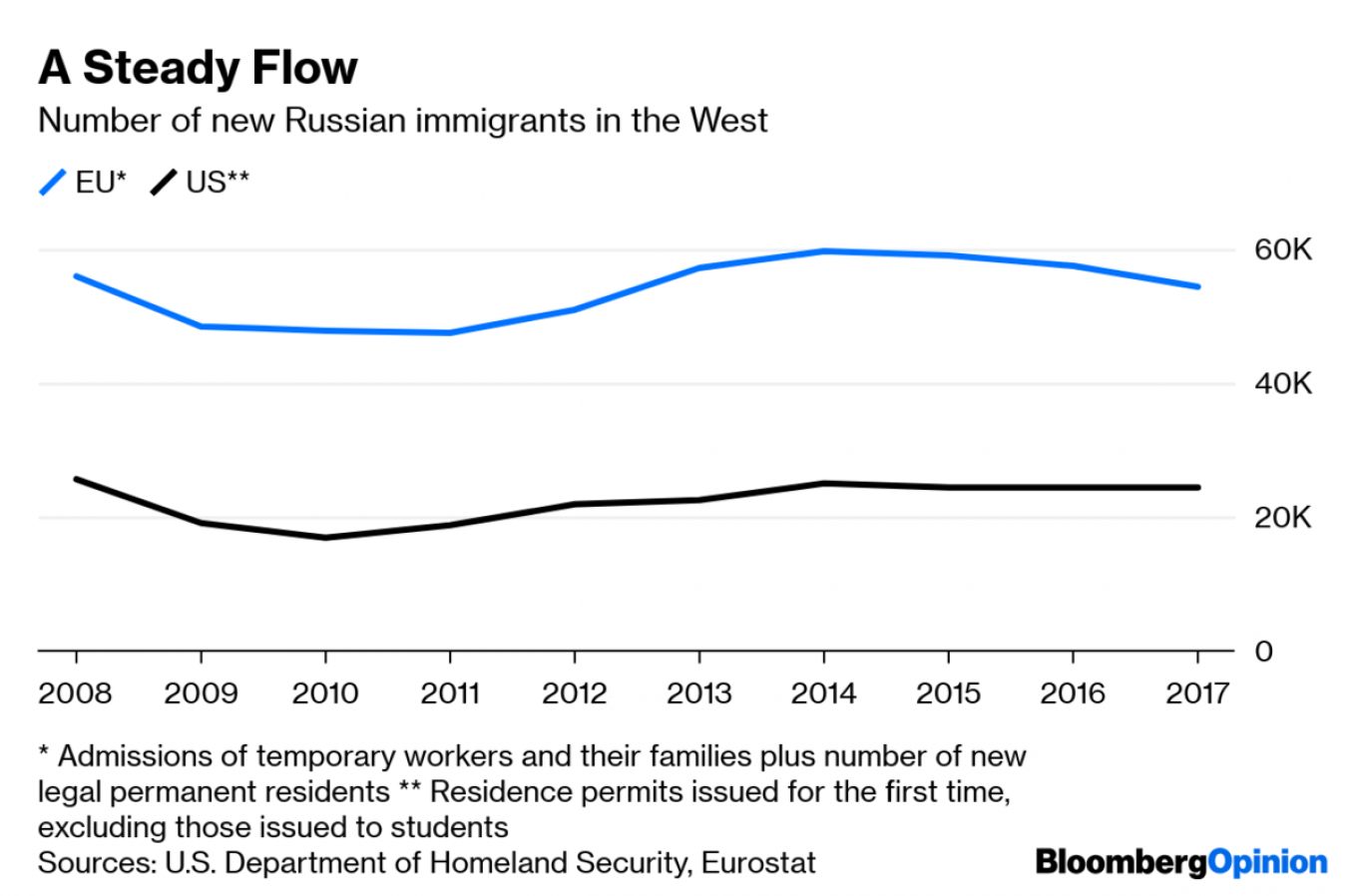

I’m not going to contrast my anecdotal experience with the Atlantic Council’s findings. Instead, consider the top-line Russian immigration data from Europe and the U.S. to understand why the report’s conclusions probably are off:

Over the last decade, the fluctuations of Russian emigration to Europe and the U.S. have been insignificant. The numbers dropped slightly in the years immediately after the global financial crisis because the West didn’t look particularly welcoming then, but the Crimea annexation didn’t cause a significant “exodus,” and neither did Putin’s 2012 re-enthronement. These milestones simply weren’t comparable, in terms of their effect on emigration, to truly momentous events like the end of the Soviet Union.

If the post-2012 wave was somehow different from its predecessors, despite the unchanged numbers, it means that as more politicized Russians emigrated, more non-politicized ones decided for some reason to stay behind despite a worsening economic situation. That would defy logic.

Beyond the small group of highly educated and politically aware people surveyed by the Atlantic Council, the bulk of Russians moving to the West aren’t anti-Putin exiles. On average, like in the 1990s, they are people seeking better opportunities for work, business and study (the number of Russians coming to Europe to study has been pretty constant so far this century). Many of them don’t end up in big cities like Berlin and New York, and most can’t afford London or Silicon Valley; they are ordinary people with above-ordinary, in-demand skills who speak foreign languages and can make it in the West, or at least try.

They represent a steady brain drain, which is a persistent problem for Russia since the last years of the Soviet Union. But finding out whether their political outlook differs from that of most Russians at home would require a better study design — and, for comparison purposes, independent field studies in Russia itself, which are increasingly hard to come by.

I’d like to be welcomed and courted in ways that previous Russian emigres weren’t. I also welcome the Atlantic Council report’s recommendation to Western politicians and media to say “the Kremlin” instead of “Russians” when discussing Putin’s moves and ideas. But I also doubt that the bulk of the recent emigration is some kind of fifth column for the Putin regime.

Defining this new diaspora as anti-Putin Russians, as Herbst and Erofeev suggest, is misleading because the label undoubtedly applies only to the self-selecting group that answered the survey. Being treated as political exiles would mean funding and jobs for my peers, people who left Russia for the same reason I did. I suspect, however, that most of the Russian community would prefer to be left alone — to integrate peacefully into the receiving countries without being reminded of what they left behind or asked to take geopolitical sides. That’s why they didn’t take part in the survey, either.

This opinion piece was first published by Bloomberg View.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.