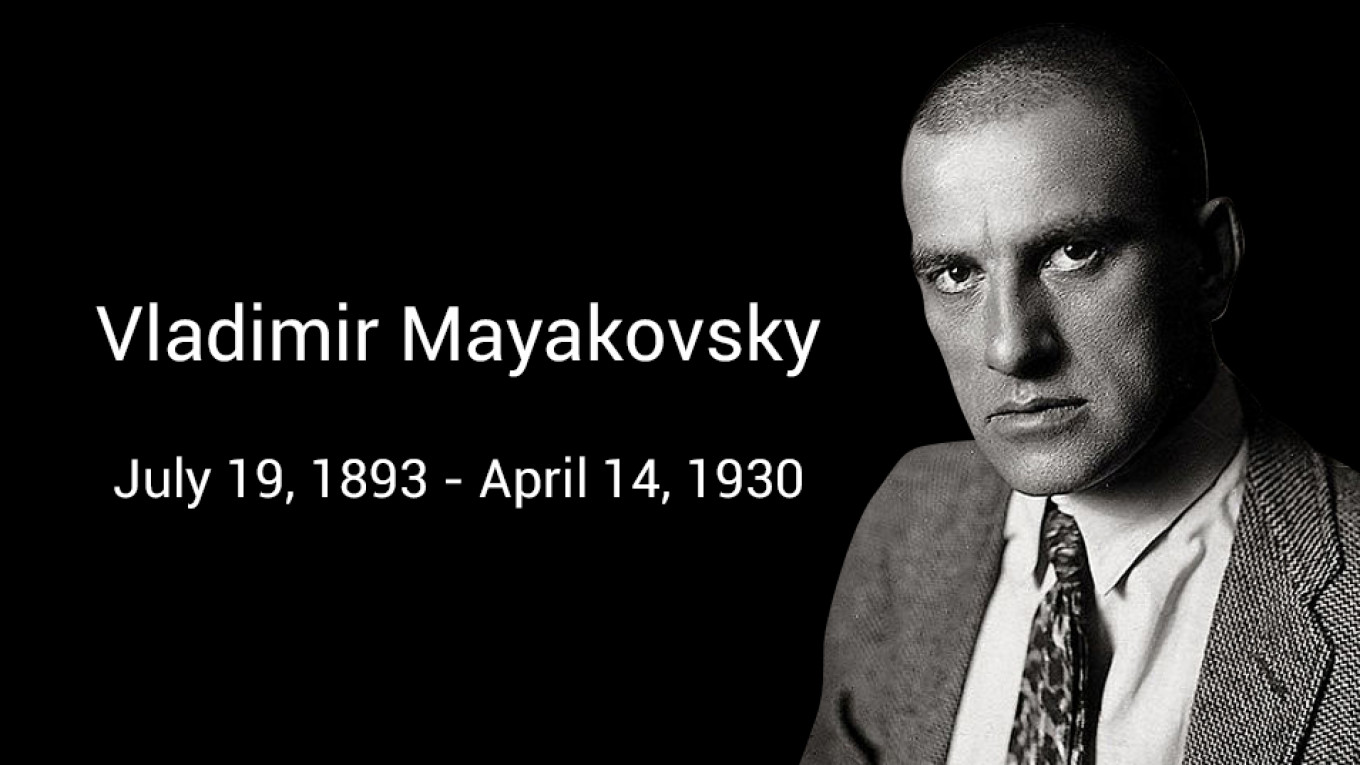

Vladimir Mayakovsky was born on July 19, 1893 in Georgia to ethnically Russian and Ukrainian parents. By the age of 14, Mayakovsky was already engaged in socialist activism. He lived in Georgia until his father died in 1906 and the family moved to Moscow. There Mayakovsky became interested in Marxist literature and joined the Russian Social Democratic Labor Party in 1907. His activities included distributing pamphlets and smuggling female activists out of prison, for which he was eventually imprisoned and placed in solitary confinement.

During his imprisonment, Mayakovsky began to write poetry. When released in 1910, he left political activism to focus on creating socialist art. The next year, he enrolled in the Moscow Art School, where he met the “father of Russian futurism” David Burlyuk and the two became friends.

Burlyuk cultivated Mayakovsky’s talent by offering financial support and books of poetry. Their relationship developed into the Hylaea group of poets and artists who challenged the artistic establishment. In 1912, Mayakovsky’s first poems were published in the group’s futurist publications, although the group was more famous for their manifesto, “A Slap in the Face of Public Taste.” The group visited 17 cities in 1913 on a riotous reading tour, which drew both large audiences and the police. This got Mayakovsky and Burlyuk expelled from their art school. Mayakovsky would go on to be the only avant-garde poet to remain in the Soviet mainstream, although later he would be heavily censored.

During World War I, Mayakovsky wrote poetry opposed to the war. In 1915, he fell in love with Lilya Brik, whose husband Osip Brik published Mayakovsky’s “Cloud in Trousers” poem. Mayakovsky dedicated many of his poems to Lilya, including “I Love” (1922) and “About That” (1923). From 1918, Mayakovsky lived with the Briks, whose home became a center of literary life. They went on to found the prominent early Soviet avant-garde journal, Left Front of Art, which opposed artistic individualism.

The October Revolution in 1917 ignited a particularly prolific period for the pro-Bolshevik poet, who extolled the proletariat with poems such as "Ode to the Revolution" (1918), "Left March" (1918), and “All Right!” (1927). He is also remembered for the 3,000-line epic “Vladimir Ilyich Lenin” written upon Lenin’s death.

From 1919, he produced propaganda posters and didactic pamphlets for the Russian State Telegraph agency. Yet Mayakovsky’s relationship with Soviet authorities grew strained. His plays such as “The Bedbug” (1929) and “The Bathhouse” (1930) were harshly criticized by organizations of proletariat writers, who no longer endorsed his poetry by 1930.

On April 12, 1930 Mayakovsky shot himself in his flat at the age of 36. A few years later, poet Marina Tsvetayeva would write of him: “For twelve long years the man-Mayakovsky killed the poet-Mayakovsky inside him, and in the thirteenth year the poet rose up and killed the man.”

More than 150,00 mourners came to his memorial service. He was buried at the Novodevichy Cemetery in Moscow.

The film below, "The Lady and the Hooligan," from 1918 stars Mayakovsky himself in his only film role as the hooligan transformed by love for a young school teacher.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.