Russian President Vladimir Putin is a man of routine, and one might have been tempted to ignore his 17th annual call-in show with voters as another pointless set piece. This year, however, the context made it more important than most of the previous ones: Putin, who’s trying to return to pedestrian domestic concerns after a long foray into great-power politics, is facing a drop in popularity and Russians’ growing fatigue.

He made a valiant attempt to show he cares, but he ultimately failed. The spirit of what happened during the more than four-hour broadcast was best described by feminist blogger Alena Popova: “The citizens of a poor country call the president of some other, rich country.”

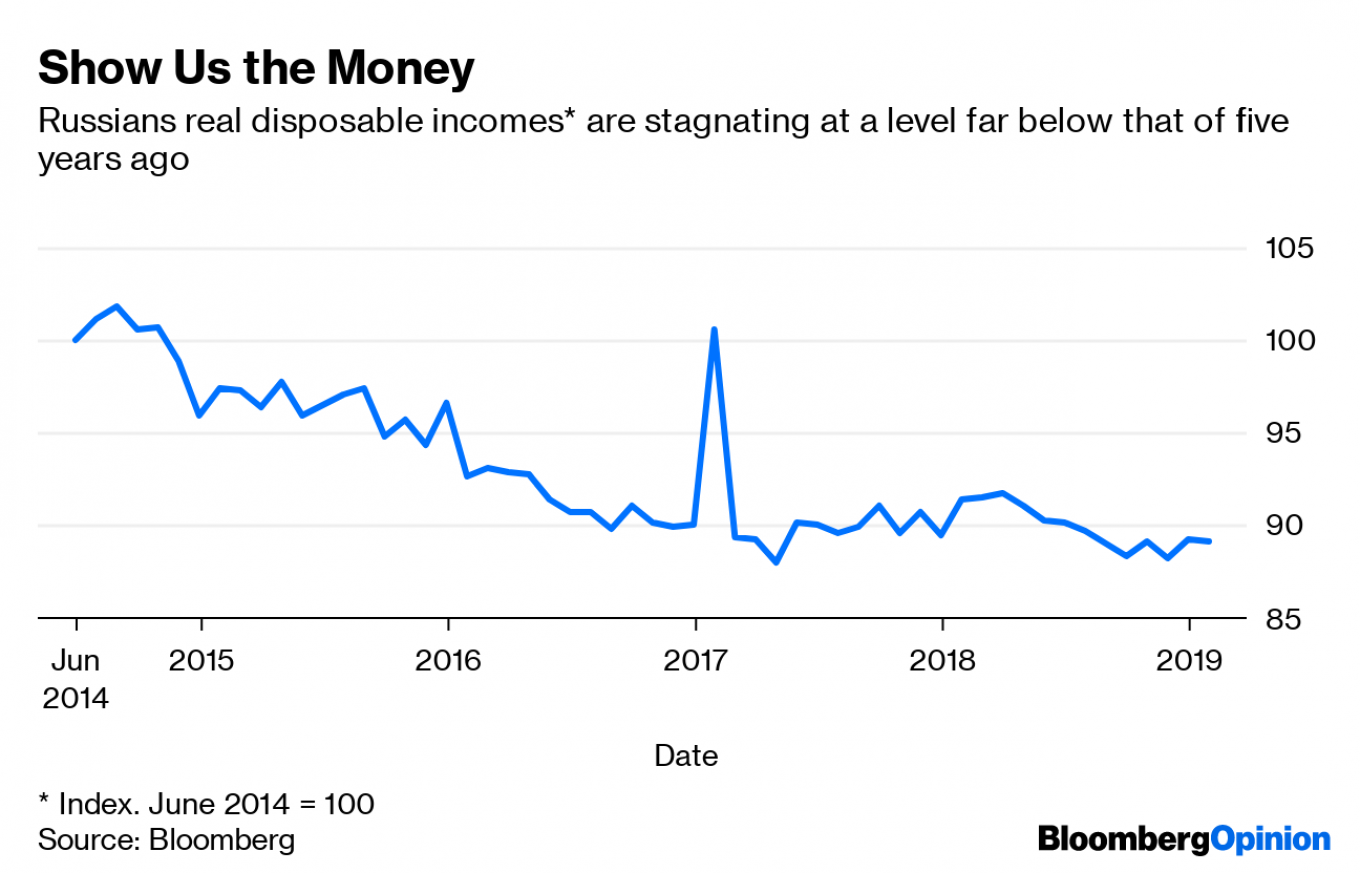

For about a year, polls have shown that Russians are no longer elated about Putin’s ability to thumb his nose at the U.S., or enthusiastic about the 2014 Crimea land grab. They are tired of incomes stagnating far below the 2014 level, irritated by an increase in the retirement age and a hike on the value-added tax, and worried the country is moving in the wrong direction. Putin’s so-called national projects — a five-year, $400 billion infrastructure and social spending plan meant to signify his domestic comeback — have failed to register in the polls.

Widespread poverty is a major issue. Former Finance Minister Alexei Kudrin, who now heads Russia’s budget accountability office, the Accounting Chamber, called it a “disgrace” this week that 19 million Russians, out of a population of 144 million, live below the official poverty line. He got a sharp rebuke from Prime Minister Dmitry Medvedev for his “populist rhetoric.”

Other clouds hung over the Putin show: A growing movement against the proliferation of landfills and poor garbage collection, and a recent episode in Moscow, where an investigative journalist was seemingly framed for a drug offense and only released after angry protests that led to Putin’s personal intervention. The arrest of the reporter, Ivan Golunov, highlighted two issues: The excessive power and corruption of law enforcement agencies, and the ease with which police can turn anyone into a drug dealer by planting small quantities of controlled substances in one’s bag or apartment.

Putin, by all appearances, took time for careful preparation before the call-in show. Official photographs showed him poring over a pile of questions he’d received ahead of the broadcast. During the show itself, the Russian president frequently interrupted the smooth production, cutting off the moderators in mid-sentence to read and answer sometimes irreverent questions that scrolled on giant screens in the TV studio.

And at the very end of the broadcast, asked if he’d ever felt ashamed, he appeared to be near tears as he recalled an episode that, according to him, occurred early in his presidency. In some provincial town, he said, an elderly woman dropped to her knees to pass him a note. “I handed it over to my aides, and then it got lost,” Putin said. “I still can’t forget it.”

The message was clearly supposed to be that Putin would never willingly ignore an ordinary Russian’s request. In reality, though, what he said in response to desperate pleas about low wages often sounded insensitive. When a teacher complained she was making just 10,700 rubles ($170) a month, Putin said something was wrong indeed: The minimum wage was supposed to be in line with the official subsistence minimum of 11,300 rubles ($179). When a civilian firefighter complained he couldn’t live on his 16,000 ruble salary, Putin said a uniformed officer in his job would be making 43,000 rubles.

He also went into a long and patently incorrect spiel about how real disposable income was the wrong benchmark, and that people should watch the growth in nominal salaries instead. Putin, who has a Ph.D. in economics, said,

Real disposable income, which statistics show are falling, consist of many indicators — that is, of income and expenses. One of the expenses these days is payments on loans, and banks offer loans to citizens, basically, against 40 percent of their salary, which, of course, is dangerous.

Not many people in Putin’s audience could follow that pseudo-economic gibberish, let alone accept it in lieu of higher wages. But as if this weren’t enough, the president followed Medvedev’s lead in kicking Kudrin: he joked that the former minister’s views appeared to be moving toward those of an old leftist opponent, Sergey Glayzev. The only way for Kudrin to take this is as a calculated insult from his boss, who clearly didn’t appreciate his input at this critical moment.

On issues that have caused recent protests, Putin’s performance was similarly subpar.

Ahead of the call-in show, residents of the Arkhangelsk and Komi regions in northern Russia, who have resisted the construction of an enormous landfill for Moscow’s excess garbage, recorded a video for Putin. Addressing him without a customary honorific, they demanded that he stop the project, which they said would poison the local water supply. On Thursday, a large crowd of locals gathered near Shies railway station, where the landfill is being built, hoping to be noticed during the call-in show.

Instead, Putin got a couple of softer questions about the problems of his “garbage reform,” meant to improve waste collection and disposal, and was given a chance to resolve a different water-related problem — that of a town near the oil city of Tyumen where residents had lived for years without running water. As usual during the call-in shows, the governors of all Russian regions and key ministers stood ready to deal with questions and take Putin’s orders via video link as needed, and Putin publicly told the Tyumen governor to deal with the complaints. Shies and the landfill project, a rallying point for environmental protesters in the last few weeks, didn’t get a mention.

Asked whether he felt personally responsible for corruption in Russia, Putin replied glibly, “Of course I do, otherwise you wouldn’t even know about any corruption cases.” And, prodded on the excessive harshness of the drug laws, he said stubbornly that he was against any kind of liberalization and that police officers simply need better supervision to prevent abuses.

The message a Russian citizen might get after four hours of this was that Putin could personally take care of any problem if it was a simple matter of giving an order. If you have a problem like that, finding a way to Putin will get results. On the tougher issues, though, Putin, as ever, finds it easier to troll and dissemble than to offer solutions. That isn’t going to endear him to anyone.

On average, the ratio of dislikes to likes in the five YouTube broadcasts of the call-in show was about nine to one. That could be skewed by Ukrainians, who often make a point of expressing their feelings about Putin when he makes him major appearances. But I doubt the Russian president will get a bump in the polls after such a performance.

Putin, of course, isn’t on the verge of being overthrown. But he’s gradually losing the voters who have backed him through thick and thin — the ordinary people in small towns and villages, who are older, poorer and more dependent on government support than the relatively cheeky urban Russians. That loss could be catastrophic — if not for Putin himself, then for his plans to engineer a smooth succession.

This article was originally published in Bloomberg.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.