As a young ballerina with the Moscow City Ballet, from 2008-2012 Varvara Bortsova lived, traveled and worked alongside dancers from across the post-Soviet sphere.

Artists in the company came from nearly every corner of the former U.S.S.R., from the steppes of Central Asia to the mountains of the Caucasus to the shores of the Baltic Sea. Many of them were born not long before the Red Flag was lowered for the last time in 1991, but they had one thing in common — a shared connection to their Soviet past.

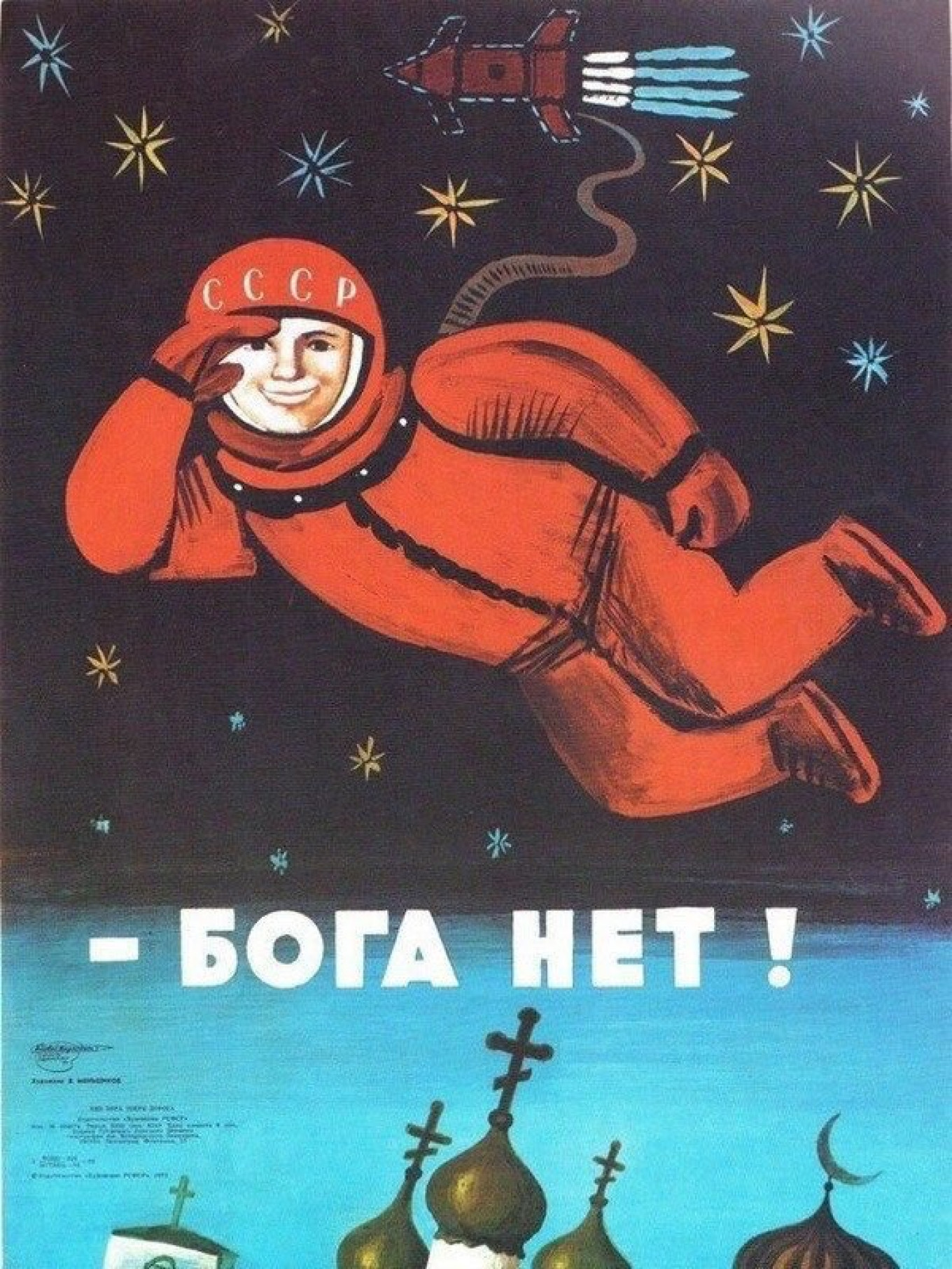

As they toured, the performers passed their free time telling stories from their lives, and Bortsova’s fellow dancers introduced her to memories of living in the U.S.S.R. that she’d never seen before: music videos from 1960s Uzbekistan, experimental 1980s dance productions, underground rock musicians and propaganda posters. Bortsova was intrigued.

“It’s always interesting to compare historical visuals to our contemporary state of things — for example, to look at political propaganda art and think about how it evolved over time,” Bortsova said. “Or to reflect on the consequences of nearly 300 million people of exceptional social and ethnic diversity having to think and create in the context of a constrained environment, essentially ‘inside the box.’”

Hungry for more, she started delving into public and family archives, digging up a vast supply of content spanning the Soviet period, including factory safety posters, home wedding footage, television commercials, fashion magazines and forgotten architectural and design experiments.

“I’d share these visuals and stories with my non-Russian-speaking colleagues and friends, and they’d always bring out a strong reaction — for them it was a whole new world, since their only exposure to Soviet culture was through history classes at school,” said Bortsova, who is now 28.

In 2016, she created a Twitter account called Soviet Visuals to act as a makeshift archive for the material she’d found. Today, Soviet Visuals is more than a hobby: It’s her full-time job. Just three years into its existence, the project has nearly 600,000 social media followers and has expanded into an online store.

Soviet Visuals’ success comes at a time when many — both in Russia and around the world — are weighing up the Soviet Union’s role in history. Nostalgia for the Soviet Union is at a 14-year high within Russia, and Stalin’s popularity among Russians has soared in recent years. A record 70 percent said they approved of his role in Russia’s history this spring, and nearly half of young people in the country have said they’re unaware of Stalinist repressions.

“This nostalgia exists in different forms — and not all who are nostalgic for the U.S.S.R. have a positive attitude toward Stalin. It should also be kept in mind that those who approve of Stalin’s activities are guided by different motives, sometimes poorly imagining what Stalin actually did,” said Russian historian and left-wing activist Alexander Shubin.

While some are happy to look at the past through rose-colored glasses, others are raising questions about the ethical quandaries of removing the aesthetics of the Soviet Union from the context of the civic environment and living conditions that its people faced every day.

Sergey Lukashevskiy, director of the Moscow-based Sakharov Center human rights organization, said that starting in the 1950s, the Soviet intelligentsia had sought to humanize the country's ideological frameworks by producing art reflecting positive Soviet values.

“Beautiful Soviet films and books — the authors of which tried to gently blur the Soviet system’s totalitarian ideological skeleton — reflected themes like kindness, mercy, freedom, humanism and nobility, but today they have lost their double meaning,” he said. “The Soviet reader and viewer knew perfectly well that reality looked different … Today, these works of art are perceived as documentary.”

He said he is confident society will someday return to a place where it can morally evaluate this history, but in today's reality, the romanticization of Soviet life is inevitable.

“Even then, the Soviet Visuals site is innocent children's fun compared to what today's official propaganda is trying to instill in children and young people,” Lukashevskiy added.

Daria Khaltourina, a Russian sociologist and anthropologist, believes that the Soviet Union’s rich cultural achievements shouldn’t be buried beneath the legacy of totalitarianism.

“The Soviet Union is a great epoch in history of not one, but several countries. ... It was also a period of modernization, mass literacy and urbanization,” Khaltourina said. “There was a lot of beauty and progress — women's rights, internationalism, educational programs, protection of workers' rights, the cult of scientific progress. It is absolutely unclear why crimes of one ruler against one’s people should make the life and work of millions of people untouchable for more than 70 years.”

Natalia Antonova, editor of the Bellingcat news website, said it’s not harmful in itself to be interested in the lives of Soviet citizens — many of whom lived full, enriched lives in spite of, not because of, their leaders.

“Obviously, you’re going to have idiots who romanticize totalitarianism and hijack these testaments in the 21st century for their own purposes, but they’re idiots — and idiots shouldn’t set the agenda for how we analyze Soviet culture,” she said.

While Soviet Visuals is aimed at giving foreigners an idea of Soviet life and aesthetics, it isn’t guilty of romanticizing the Soviet way of life or revising its history, said Boris Kagarlitsky, a Marxist theorist and sociologist who has been a political dissident in the Soviet Union and in post-Soviet Russia.

“Rather, it is free from anti-Soviet propaganda clichés, which naturally irritates those for whom the fight against the ‘accursed totalitarianism’ of the past has become a profession,” he said.

For her part, Bortsova said she has no political agenda and works to keep the site as neutral as possible. The site features no images of Stalin, for example. The most common reaction she gets from former Soviet citizens is bewilderment.

“They find it difficult to understand why a washing machine design or some old footage from a Soviet outdoor disco is so interesting — because for them, this was just ordinary life and not anything special,” she said.

Still, the feedback she receives tends to be “overwhelmingly positive,” with readers filling her inbox with their own stories and images.

“Every once in a while, someone will complain that the content is too pro-Soviet or too anti-Soviet — and for me, that’s great news, because as long as it’s both types, it’s an indicator of the fact that I’m able to keep it as neutral as possible.”

Obviously, you’re going to have idiots who romanticize totalitarianism and hijack these testaments in the 21st century for their own purposes, but they’re idiots — and idiots shouldn’t set the agenda for how we analyze Soviet culture.

While she runs the site by herself, Bortsova says the job has gotten easier as the project has grown. Content flows in from her audience, as well as from friends and family. For the web store, she commissions artists from across the post-Soviet space to create designs for everything from T-shirts to pillows.

The store’s best-selling items are a poster of cosmonaut Yury Gagarin saying “There is no God!” as he floats through space, and an illustration of Laika, the first dog in space, and her rocket.

Both items speak to a lingering nostalgia for the Soviet Union’s historical achievements — but Bortsova says she’s most interested in showing the lesser-known elements of people’s everyday lives that don’t make it into the history books, no matter how trivial they might seem.

“The mainstream stereotype tends to be that anything Soviet is by default grey, bland and uninteresting,” she said. “I hope that exposing my followers to the sheer spectrum of color, humor — intentional or unintentional — and ideas behind the Iron Curtain will spark their curiosity.”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.