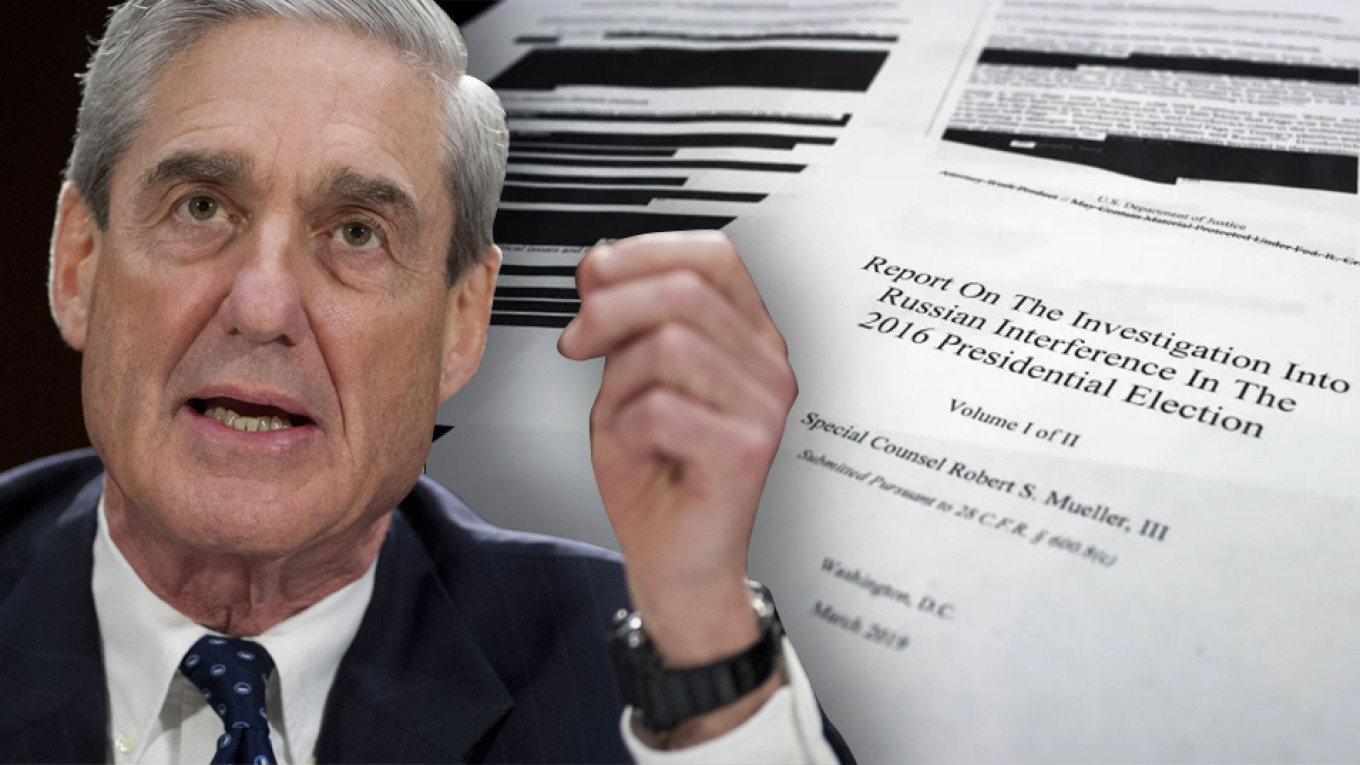

The investigation by Special Counsel Robert Mueller was supposed to be the biggest deterrent to President Donald Trump’s oft-stated desire to “get along with Russia” and its President Vladimir Putin. But now that Trump is as free from the Mueller shadow as he’s ever going to be, U.S.-Russia relations aren’t improving: The two countries still have nothing substantive on which to agree.

Secretary of State Mike Pompeo’s visit to Sochi, Russia, on Tuesday and his meetings with Putin and Foreign Minister Sergei Lavrov have only confirmed that. This is a new normal that probably can only be changed, for better or for worse, by some momentous event like the dismantling of the Putin regime.

Before the Mueller report came out, the dysfunctional relationship was on hold. Trump had refused to meet with Putin at the G-20 summit in Argentina in November, 2018, citing as the reason Russia’s seizure of two Ukrainian ships in the Kerch Strait. The relief at Mueller’s inability to find evidence of a Trump-Russia conspiracy, however, prompted a resumption of contact, though Ukrainian sailors remained in Russian captivity.

Trump and Putin spoke on the phone on May 3; according to the Kremlin readout, it was on Trump’s initiative. Trump recounted that Putin was sarcastic on the call about Mueller’s conclusions: He “sort of smiled when he said something to the effect that it started off as a mountain and it ended up being a mouse.” Trump clearly appreciated it, but otherwise the fruitless conversation circled the same old bases - Ukraine, North Korea and Venezuela, which is now increasingly pushing Syria lower down the list of obligatory subjects.

Post-Mueller, some Russian and Ukrainian commentators revived talk of a potential grand bargain between Putin and Trump involving Venezuela. Crudely put, such a deal would involve an end to Russian support for Venezuelan dictator Nicolas Maduro in exchange for a cessation of U.S. support for the Ukrainian authorities anti-Russian course. Similar ideas once circulated involving Syria in Venezuela’s place – but no grand bargain was reached then and none will be reached now.

Putin never fully controlled Syrian President Bashar Al-Assad; nor does he control Maduro. He also is less able to defend the Venezuelan dictator militarily than he did Assad. Conversely, Trump can’t do much to change Ukraine’s course: Ukrainians aren’t passive bystanders in their own country, and they’re overwhelmingly against bowing to Putin.

This reality is apparent to both sides. Asked last week whether a U.S.-Russian deal was possible on Venezuela, Lavrov replied with his customary dark irony, “It’s Trump who usually prepares deals.” He knew, of course, that the two presidents’ discussion of Venezuela on the phone call had been limited to Putin’s token assurances that he wasn’t meddling there and a shared desire to get some humanitarian aid to starving Venezuelans.

The bizarre, and by now familiar, ritual of touching on a well-known list of issues without making any reportable progress on any of them was repeated during Pompeo’s visit. Both Putin and Lavrov mentioned the end of the Mueller investigation in public remarks during and after the meetings as a reason to expect a more constructive relationship. But it appears to have changed nothing of substance.

The secretary of state said he was “excited” about the Syria part of the conversation, hinting that some agreement was found on “how to move the political process forward,” specifically on getting various Syrian factions together to discuss forming a non-sectarian government in line with a 2015 United Nations Security Council resolution. But both Putin and Trump have limited influence on that process, and Pompeo admitted, “I’m not sure we have all the capacity of that.”

The Mueller investigation cast a pall on the U.S.-Russian relationship, making sure any Trump impulse to try to normalize it was drowned in a bipartisan chorus of condemnation in the U.S. But now that Trump has been cleared of conspiracy (Putin, of course, wasn’t cleared of election meddling), it’s been revealed that the root of the problem is different. While the Obama administration had ideological issues with Putinism, the Trump one can’t find any benefit in doing business with Putin.

As Fyodor Lukyanov, one of the most astute foreign policy commentators in the Putin camp, wrote in the government daily Rossiyskaya Gazeta on Wednesday, “In Trump’s world of trade balances, Moscow is absent — or rather, it’s occasionally present as an obstacle, for example on the path of U.S. liquefied natural gas to Europe.”

Pro-Putin commentators in Russia have often tried to finger U.S. domestic politics as the main hindrance. If it were up to Trump, the narrative went, there’d be a thaw. In reality, though, Russia is so irrelevant to Trump’s economic and trade agenda that economic issues don’t even appear to crop up in any U.S.-Russian talks. Putin’s problem is, and has always been, that he can’t deal with Trump on the only basis the U.S. president really understands: He’s unwilling to trade geopolitical advantages for any economic enticements Trump might offer, and he has nothing to offer Trump on trade and investment.

Trump has agreed to meet with Putin at the next G-20 summit in Japan in late June. The optics may be better than their meeting in Helsinki last year, but the ingredients for any kind of deal are still missing. It’s easy to share the pessimism of Carnegie Moscow Center Director Dmitri Trenin who wrote on Tuesday that in the short term, the U.S.-Russian relationship “will likely get worse before it gets even worse.”

This article was originally published in Bloomberg Content.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.