Winter is coming and it promises to be bleak for Ukraine as Russia is clearly preparing to cut its neighbour out of its gas transit system completely. In an exclusive interview with bne IntelliNews the executive director of Ukraine’s national gas company Naftogaz, Yuriy Vitrenko, says that the company’s base-case scenario is that all deliveries of Russian gas, including the transit gas to Russia’s European customers via Ukraine, will cease on January 1, 2020.

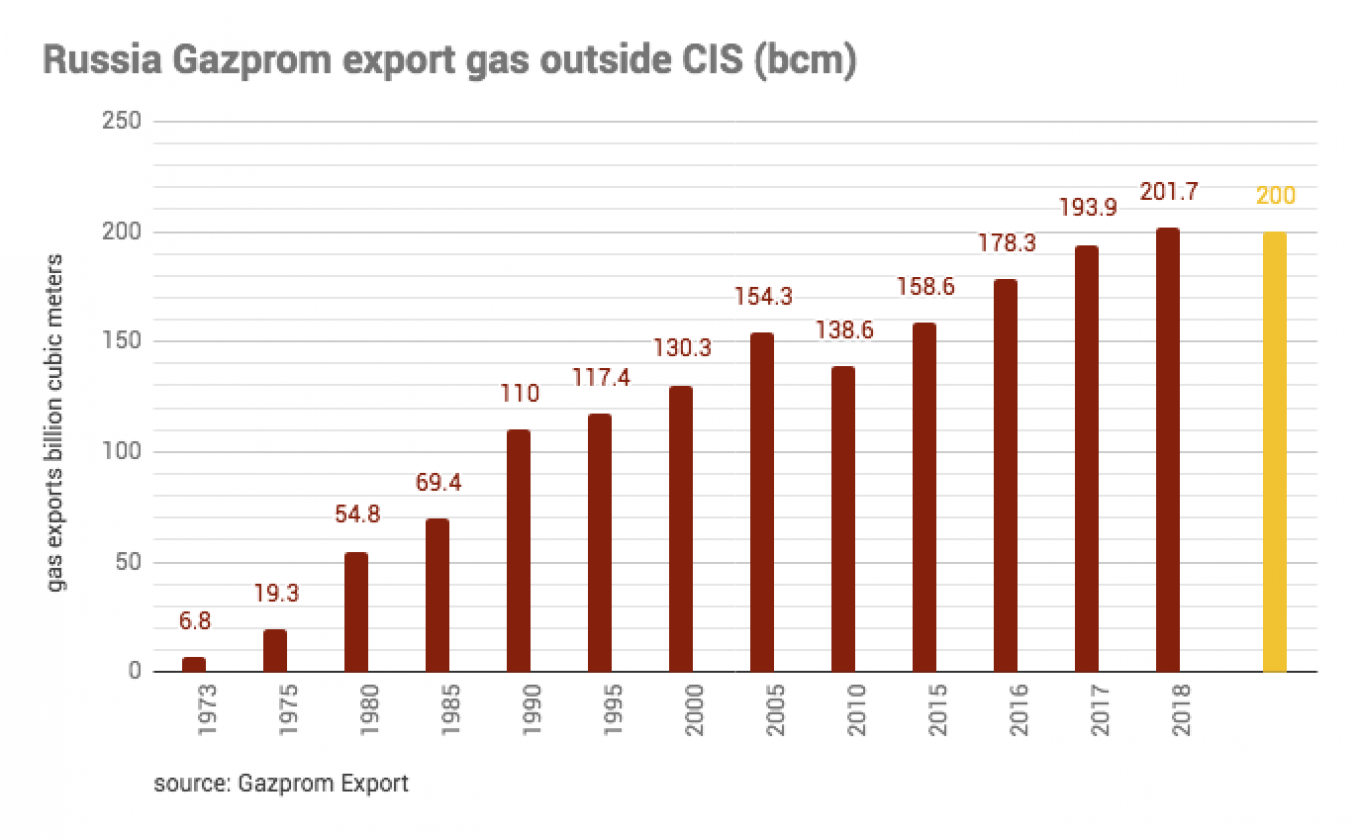

And Russia is preparing to cut Ukraine off even if the controversial Nord Stream 2 pipeline is delayed or blocked altogether. Nord Stream 2 will add an extra 55 billion cubic metres (bcm) to Russia’s pipelines running to Europe that can replace most of the 65bcm that travels through Ukraine each winter.

If Russia does cut Ukraine off before Nord Stream 2 is ready then it will have to reduce its deliveries to its contracted minimums and even then there will probably be a shortfall, says Vitrenko. That means Europe can look forward to a deficit of gas on the market, and soaring prices. For Ukraine the outlook is even bleaker as it may end up with no gas imports at all from either its eastern or western border and it will have to reverse the flow in its domestic pipelines to pump gas from western storage tanks to supply the northern regions. Last time it tried that in 2009, the system nearly collapsed.

All this could be avoided if Russia and Ukraine can come to some compromise. The existing gas supply and transit deal will expire at the end of this year, and before a new deal can be signed disputes over the old one need to be resolved. But here too talks are fraught and the legal writs are flying.

The Stockholm arbitration court’s decision in December 2018 ordered Gazprom to pay compensation of $2.6 billion to Naftogaz, which the Russian company has refused to do. With interest, the amount the Russians owe is now $2.8 billion and Ukraine has begun the process of trying to seize Gazprom assets in European countries in lieu of payment.

“They are not paying. That is why we are enforcing the tribunal’s award all over the world, including in some jurisdictions like Luxembourg. Gazprom’s legal right to refuse payment is thin,” says Vitrenko, as the 2008 deal, signed by then-prime-minister Yulia Tymoshenko, included a clause that any dispute could be heard in Stockholm and the parties are bound by its decisions. Indeed, the irony of the case is that Gazprom began the proceedings in Stockholm, according to Vitrenko.

“On one hand they are challenging all the awards in the court of appeal in Sweden, both the final awards in the supply and transit cases, but also the separate awards in the supply case decided on the take or pay arbitration,” says Vitrenko, referring to the court’s decision to award some money to Gazprom from the transit part of the deal, but more to Naftogaz, resulting in a net payment of $2.6 billion from Gazprom to Naftogaz. “In addition they are trying to launch a new arbitration.”

The rules clearly say that Gazprom is obliged to pay the award to Naftogaz as soon as the court reaches its decision, even if Gazprom subsequently appeals the decision, according to Vitrenko.

Naftogaz has been trying to lay its hands on Gazprom assets in Europe, but has not had much luck.

“Yes and no. On one hand we were able to freeze their assets in the UK and the Netherlands. We were also successful in the US and Luxembourg. But in terms of real enforcement – in terms of actually getting cash – it hasn't happened yet,” says Vitrenko.

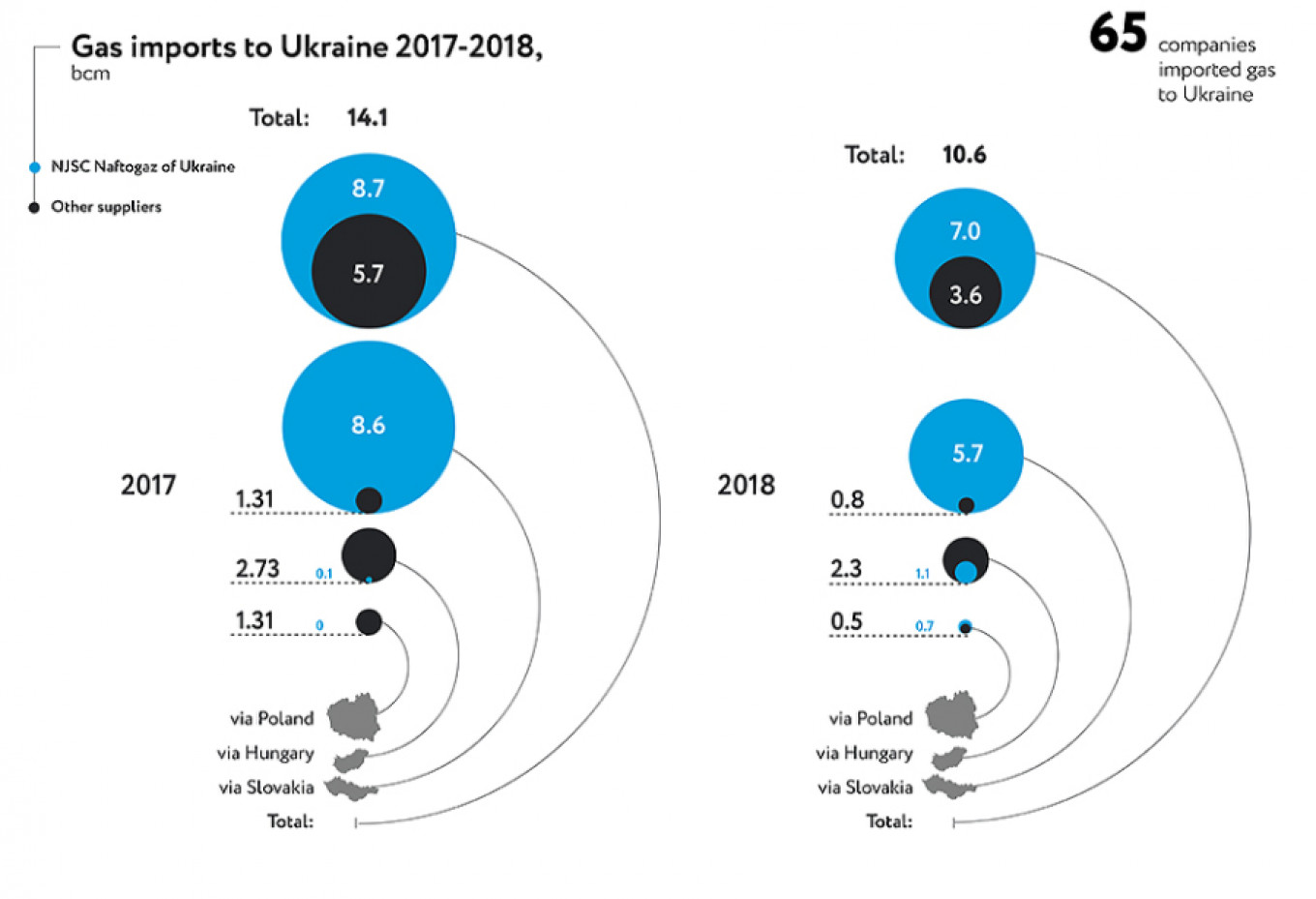

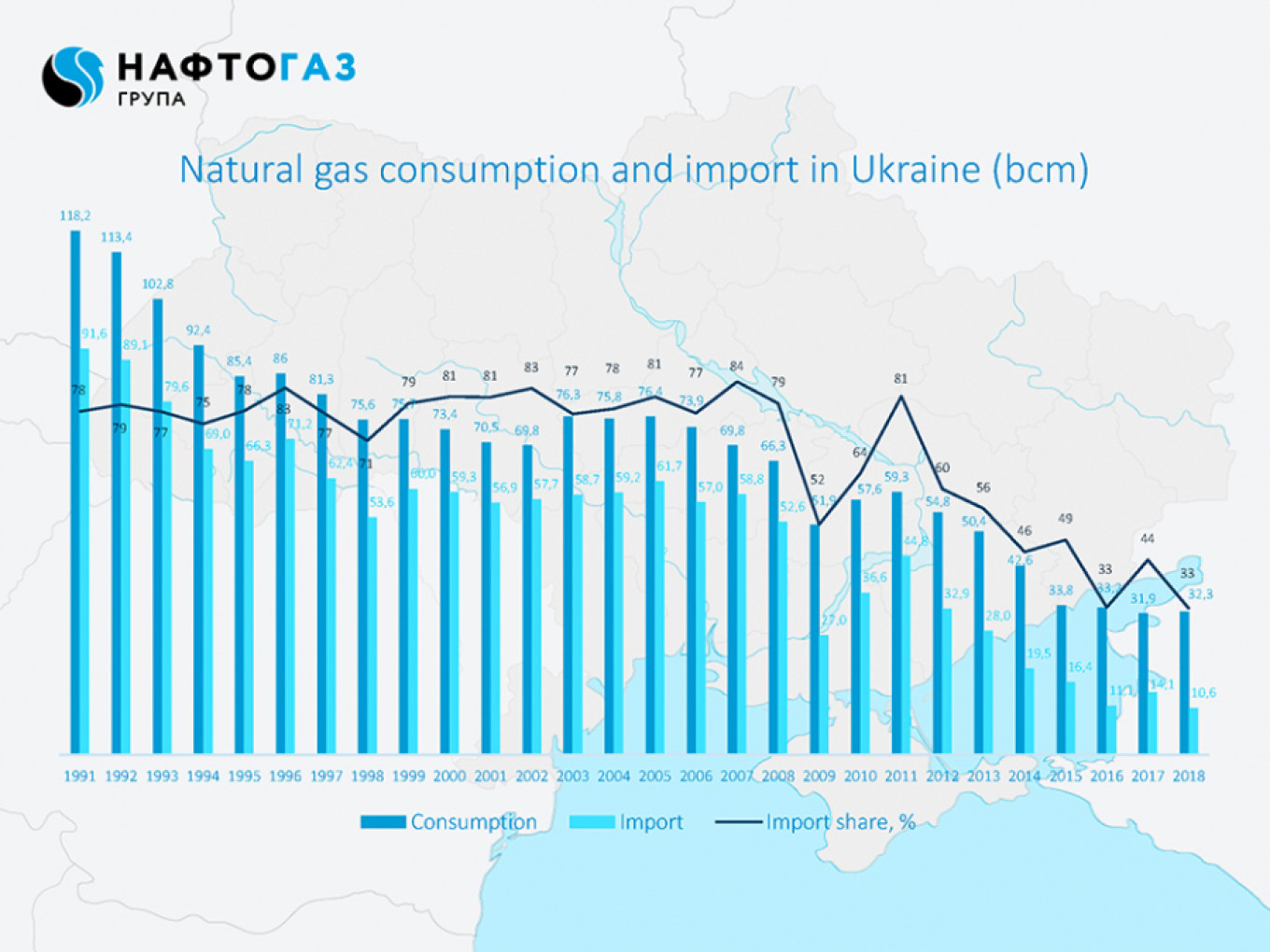

The relationship between Gazprom and Naftogaz has broken down. In the pre-war days Ukraine used to import some 45bcm of gas from Russia a year for its own use, in addition to the gas transiting the country through the ironically named Druzhba, or “friendship,” pipeline. But since the rows over money began Ukraine has stopped all deliveries of gas from Russia and has not received any Russian gas for more than 1,000 days.

“We are an important transit route and at the same time we used to be their biggest customer, but now we are not buying from them at all. The last supplies stopped in 2016. We are buying all the gas we need from Europe,” Vitrenko says.

On the face of it, this European gas is more expensive than Russian gas, but in fact it’s more complicated than that.

“If Gazprom doesn't abuse its position as the dominant gas supplier and if Gazprom supplied its gas to Ukraine at a fair market price — a price you’d see in a competitive market — then the price from Russia would be lower than the price from Europe for the simple fact that it would not be transported to Europe and then back to Ukraine, so you would save on the transport costs. But unfortunately, if you look at our contract, before we were successful in the arbitration to revise the prices, the price we paid was higher than the price we are being charged by Europe.”

The change of price was a key part of the Stockholm decision and has massively altered the profitability of Naftogaz. In the previous regime under the Tymoshenko contract with Gazprom, Naftogaz was shelling out a net $5 billion a year to Gazprom for gas supplies and booking this amount as a loss. But since it has begun importing gas from Europe, coupled with the increases in domestic tariffs, the company is now making a net $600 million in profits, says Vitrenko.

Now Ukraine is facing the very real possibility that Gazprom will bypass Ukraine completely by sending all its gas to Europe via Nord Stream 2, leaving the Dzuzhba pipeline empty.

Another key element of the Stockholm decision was that the court ordered Gazprom to restart its deliveries to Ukraine at the start of last year, albeit at the low level of 5bcm a year, and Kyiv even prepaid Gazprom for the deliveries. The gas never showed up.

“They were supposed to resume supplies in March 2018 and we even prepaid for this, but they failed to supply. Now in a new arbitration we will be claiming damages because of the failure to supply,” says Vitrenko.

Gazprom is still sending a considerable volume of gas via Druzhba but with 1,125 kilometers of the 2,200 kilometer Nord Stream 2 completed as of the end of April, even the transit business, which earns Kyiv some $3 billion in revenues a year, looks like it will come to an end. With only $20 billion in reserves in a $100 billion economy, the loss of the transit business will come as a heavy blow for the already struggling economy.

Two recent developments mean that Nord Stream 2 may not be completed on time and even Gazprom admitted in a statement on April 30 that the completion of the pipeline on time is now in doubt.

The problem has been the passage into law of the EU’s third party energy directive on April 15 and the refusal by Denmark to grant Gazprom construction permits to build the underwater pipeline in its part of the Baltic Sea.

Extending EU rules to non-EU pipelines — particularly those outside EU territory — the directive will force Gazprom to “unbundle” or hand over operation of the line to a company independent of Russia’s state gas producer. However, Gazprom maintains a jealously guarded monopoly over gas exports from Russia and will be very reluctant to share the right to export with anyone. Currently the only other entity allowed to export gas is privately owned Novatek, which is limited to exporting liquefied natural gas (LNG). The upshot is that even if the pipeline is completed on time it may have to run half empty.

Likewise, Gazprom is preparing legal action against Danish regulators, who are refusing to grant construction permits for Nord Stream 2, which could also delay completion.

At the end of March, the Danish regulatory authority mentioned that it did not plan to examine the previous two Nord Stream 2 route applications until the company had considered an alternative route in the waters south of Bornholm. All the other countries on the route — and especially Germany, where the pipeline makes landfall — have given Gazprom permission. The company is now proposing a new route passing through a special economic zone, and not Danish territorial waters, which limits the sovereignty of Danish watchdogs over the area. The whole row may end up in court, which in itself will delay the completion of the pipeline.

“The pipeline may be delayed but it is not guaranteed as it now depends on the Danish authorities, according to Gazprom,” says Vitrenko. “The way we see it is that Gazprom can work without any transit through Ukraine as soon as January 2020 even if the pipeline is delayed.”

Russia is clearly getting ready to cut Ukraine off from the transit business in January even if Nord Stream 2 is not ready. Gazprom is already pumping extra gas into its European storage facilities this spring ahead of a showdown this winter, according to Vitrenko. At the same time, the LNG supplies from the giant Russian Yamal fields are being sent to Europe.

“If you look at Gazprom’s minimum contractual obligation quantities then we see they can cut supplies to Europe to the contractual minimum and be ok without using the Ukrainian transit route just by using gas stored in Europe and maybe buying some extra LNG from Yamal and swapping delivery with their customers,” says Vitrenko.

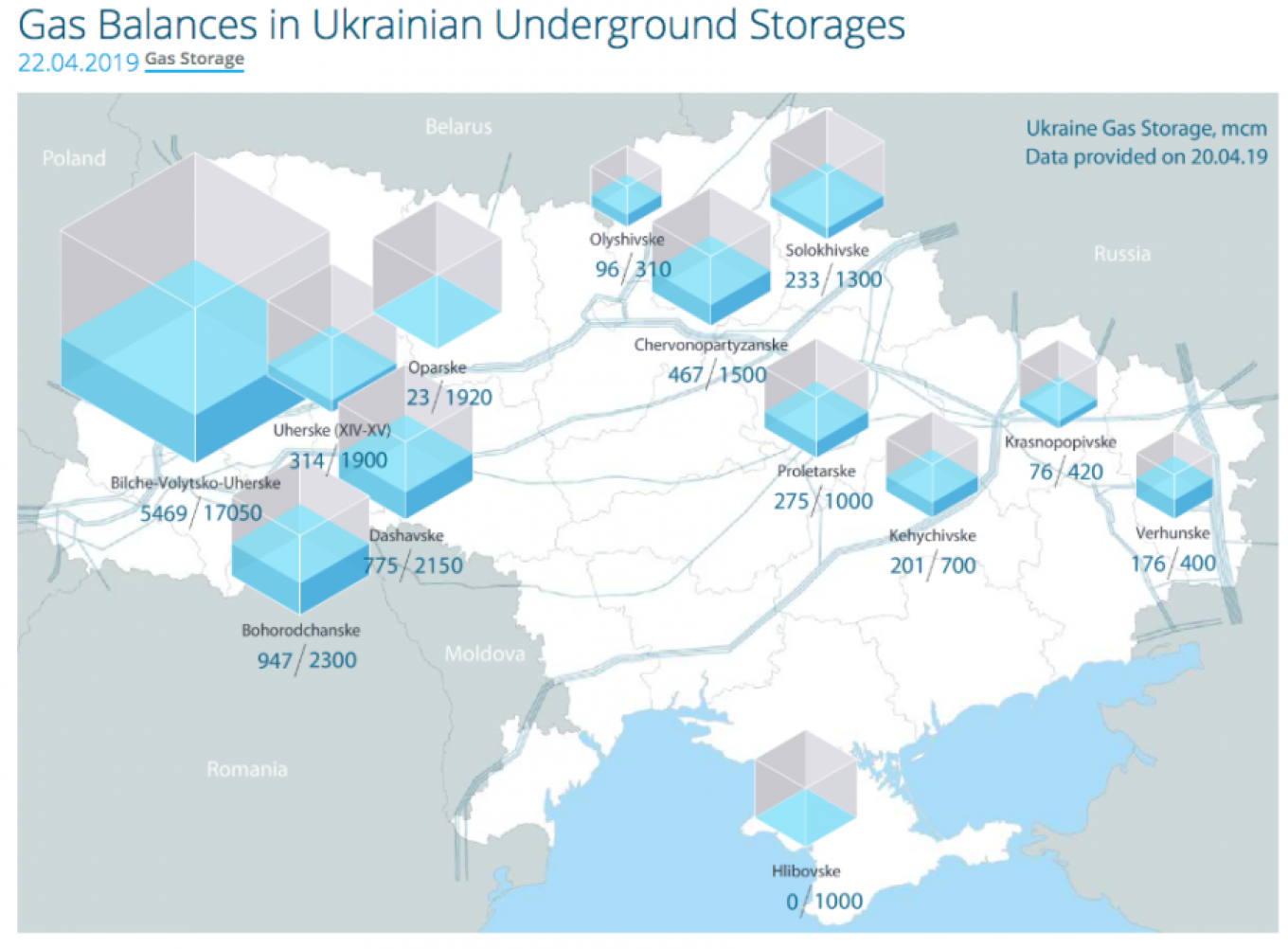

Gazprom has access to eight European gas storage facilities that can hold up to 5bcm of gas, reports Vedomosti. However, Gazprom can rent more space if it wants to store more gas and has already done so in 2017 and 2018 to a total of 8bcm, the paper reports. The bulk of the Soviet-era gas storage facilities to prepare for winter deliveries to the EU from Russia are based in Ukraine and can hold up to 30bcm of gas.

Gas and oil swaps are a common way of getting physical product to an end user. As oil and gas are commodities, and thus all the product on the market is supposed to be identical, rather than physically transport oil around the world, traders commonly swap some oil far away from their customers with other oil that is close by. For example, Yamal LNG gas on its way to Japan can be swapped with Norwegian gas on Europe’s doorstep to make up the shortfall.

“With the storage and swaps they [Gazprom] may be short 5bcm-10bcm [from their minimum contract delivery obligations] but it is not critical for them,” says Vitrenko. “It also means that a shortage of gas in Europe will inevitably lead to some price increases in the European market… Our base scenario is there will be no transit [of Russian gas] through Ukraine from the first of January, 2020.”

The loss of the transit fees will be a serious blow to Ukraine’s already weak economy. Vitrenko points out that $3 billion is about 3 percent of GDP, but if you add the multiplier effect — the money is used to pay salaries and the workers buy goods made in Ukraine — then actually this money is worth 4 percent of GDP.

“Our GDP growth is expected at 2.9 percent in 2020 according to the IMF. So if you subtract 4 percent from 2.9 percent then you get a recession next year of 1.1percent if there is no transit,” says Vitrenko.

On top of the economic consequences Ukraine may have problems supplying itself with enough gas this winter. Of the 30bcm-35bcm of gas that Ukraine consumes, it already produces some 20bcm of its own from gas fields in the west of the country. To supply the northern regions Naftogaz often swaps its own western production stored in the west with Russian gas transiting and passing by the regions on the northern border. If there is no Russian transit gas then gas from western Ukraine will have to be physically sent to the northern regions by reversing the flow in local pipelines.

“We tried to do this in 2009 when Russia interrupted the supply, but it was like a crisis scenario. We were able to maintain the system in this reserve-flow mode for a couple of weeks, but then some of our compressor stations were on the brink of collapse. We modernised some of these compressor stations, but if it happens again it would be a new crisis scenario,” says Vitrenko.

To add to the headaches, if Russia does try to muddle through the coming winter by cutting Ukraine off and relying on minimal contractual deliveries, plus whatever it has in European storage, the subsequent gas shortage in the EU means that Ukraine cannot rely on its western partners to continue to supply it with what will ultimately be reduced amounts of Russian gas flowing into Europe. If its partners can’t meet their own domestic needs then Ukraine will be cut off from gas on both its eastern and western borders.

“In this case Ukraine will be left without any imported gas,” says Vitrenko, emphasising this is still only a hypothetical scenario.

Kyiv has already approached the European Commission and is calling for a regional effort to model the gas flows for this worst case scenario to see what will happen, as the entire European gas network has to be taken into account. There is other gas in the system as Europe imports about a third of its overall gas needs from Russia, but the distribution is very uneven and some countries in northern Europe are almost exclusively dependent on Russian gas for heating during the winter.

“We agreed with the EU that we would do this work later this year, but we haven’t done it yet and that is disturbing,” says Vitrenko.

This article is based on a bne IntelliNews podcast. Listen to the full interview here

Signup to receive bne IntelliNews podcasts alerts here

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.