Ukraine’s presidential election is going to a run-off, with comedian Volodymyr Zelenskiy enjoying a hard-to-overcome lead over incumbent Petro Poroshenko. If the political novice becomes president, the nation will get a much-needed chance for progress, but the opportunity will be all too easy to squander.

The vote is, in effect, a referendum on the course Ukraine has taken since the 2014 Revolution of Dignity. Barring any last-minute shenanigans, the verdict is clear: Poroshenko messed it up.

With about three-quarters of the votes counted on Monday, Zelenskiy was leading with more than 30 percent support and Poroshenko was second with less than 17 percent. No presidential candidate in Ukrainian history has been able to overcome such a first-round deficit.

Eight out of 39 candidates received more than 3 percent of the vote, and most of their supporters are likely to back Zelenskiy rather than Poroshenko in the second round.

The Kolomoisky factor is the key to what a Zelenskiy presidency would look like. If, as Poroshenko and many others have assumed, the comedian is beholden to the billionaire, it will look a lot like the previous presidency.

That means a shop front of liberal and anti-corruption reforms will hide a bonanza for the head of state’s friends and partners – except Zelenskiy, less experienced than Poroshenko in Ukraine’s dog-eat-dog politics, is unlikely to consolidate power as effectively as the incumbent.

In this scenario, Ukraine is in for an oligarchic free-for-all, publicly reflected in the fractious parliament likely to result from October’s legislative election. That would be a throwback to earlier times, and a hindrance to investment in the resource-starved Ukrainian economy.

But if Zelenskiy, the media-savvy business tycoon, manages to shake off Kolomoisky’s influence, Ukraine could take a leap forward.

The candidate has received support from several leading reformers responsible for key economic achievements under Poroshenko, among them overhauls procurement and the tax system. They had been squeezed out of government and now want a second chance.

Zelenskiy has also signaled he would work with former Georgian President Mikheil Saakashvili on fighting corruption – a courageous statement given the latter’s stormy history in Ukraine. Poroshenko granted him Ukrainian citizenship and appointed him governor of Odessa, but then revoked the fiery Georgian’s citizenship after he accused the president of covering up graft.

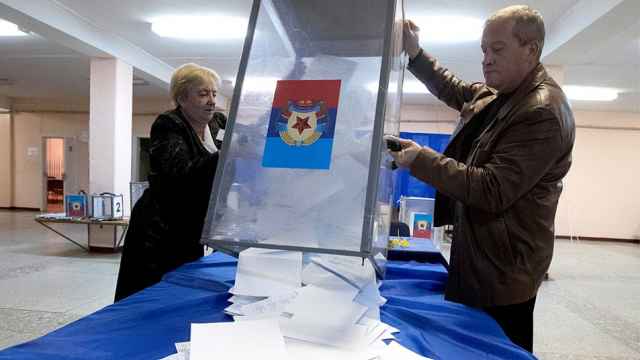

There may also be progress on an issue that Poroshenko has been unable to tackle to most Ukrainians’ satisfaction: ending the war in the country’s east. The president’s intractable opposition to the secessionist demands of the “people’s republics” of Donetsk and Lugansk, both now more-or-less run from Moscow, has led to a dead end in the negotiations with Russia.

Zelenskiy has said he is willing to make concessions on the eastern regions’ cultural identity, which is closer to southern Russian than to western Ukrainian. That might lead to some kind of an internationally brokered solution, such as a Ukrainian election in the regions held under external control, and the abolition of the “people’s republics.”

Zelenskiy, however, would be unlikely to surrender to Putin in eastern Ukraine – if only because of the Kolomoisky factor. The oligarch had funded nationalist volunteer units which, before Poroshenko began investing in the regular army, had halted the spread of separatism.

For Ukrainian oligarchs, subjugation by Russia would mean being squeezed out of their own country by Putin’s friends and state-owned Russian companies.

In between these two scenarios – the oligarch’s puppet and the swamp-drainer in chief – there is a third one: Zelenskiy the weak, inept leader unable to get his hands on the levers of government.

That wouldn’t necessarily be a disaster. Indeed, the country would be pushed further along a distinctly European route, toward parliamentary democracy. As it is, the Ukrainian parliament makes the key economic appointments to the cabinet.

So October’s legislative election will be vital for the country’s pro-European forces: Regardless of who is president, they need to be able to build a strong pro-reform, anti-corruption coalition.

Ukraine has rarely chosen its leaders well, and the choice it faces is between two highly imperfect candidates. But one of them has already had a go at running the country, and has little to show for it. A new, inexperienced, anti-establishment candidate brings uncertainty, but may be better than more of the same bungling, corrupt, and increasingly authoritarian government.

Then again, in Ukraine, it could always be worse. A comedian’s success on April Fools’ Day isn’t necessarily a good omen.

This opinion piece was first published by Bloomberg View

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.