How do you save a church? Call in a heavenly choir.

That’s what St. Andrew’s Anglican Church in Moscow decided to do.

To raise funds for desperately needed repairs to their historic 135-year-old church, the church invited the Stas Namin Theater to perform their production of “Jesus Christ Superstar” on April 2. And Stas Namin immediately agreed because he spent many years of his life in this church — recording rock music. Confused? Churches, foreign owners, property rights, and Soviet power make for complicated stories.

A bit of England three blocks from the Kremlin

The history of the English community in Moscow begins in 1553 when the first merchants arrived, set up a trading company, and were allowed to worship according to their own customs. But the community really burgeoned in the early 19th century, when manufacturers, industrialists, engineers and other specialists came to Moscow to establish businesses and families.

In 1825 the community bought a plot of land at 8 Voznesensky Pereulok (“Ascension Lane,” named after the small Church of the Ascension at the end of the street). In 1829 they converted the house on the property into the British Chapel, which served the community for several decades before falling into disrepair.

In the 1870s the now large British community began gathering funds to build a proper church, one that would be “quintessentially English in its construction.” Among the families that donated to the fund were the McGills, the owners of successful textile mills and generous philanthropists, who had already built hospitals, schools and a dormitory for English governesses; Andrew Muir and Archibald Mirrielees, whose apartment store near the Bolshoi Theater was the last word in modernity — it even had a lift! — and is now known to everyone as TsUM; and William Hopper, an owner of a machine-tool plant who set up a football pitch for his workers — the first recreational facility for employees in the city.

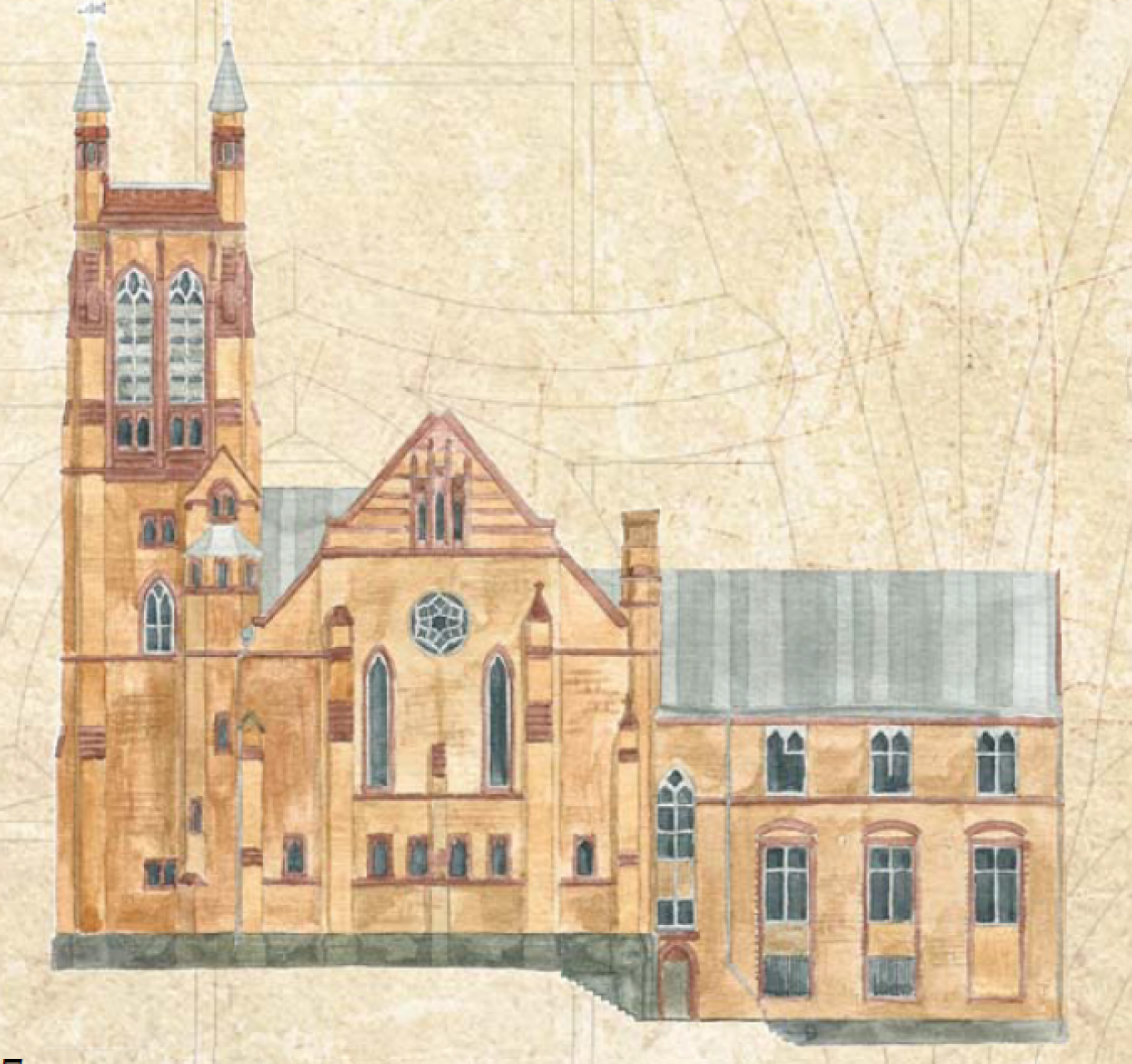

The church, designed by Richard Knill Freeman, was constructed over two years and completed in 1884. St. Andrew’s, named for the patron saint of Scotland and Russia, remained the heart of the British — and not only British — community until the Revolution.

Machine guns and music

In 1920 the church was closed by the Bolshevik government and the property expropriated. During the Civil War years, a machine gun post was situated in the tower to put down any signs of rebellion. The now empty church was first used as communal housing and then as part of the Finnish Embassy.

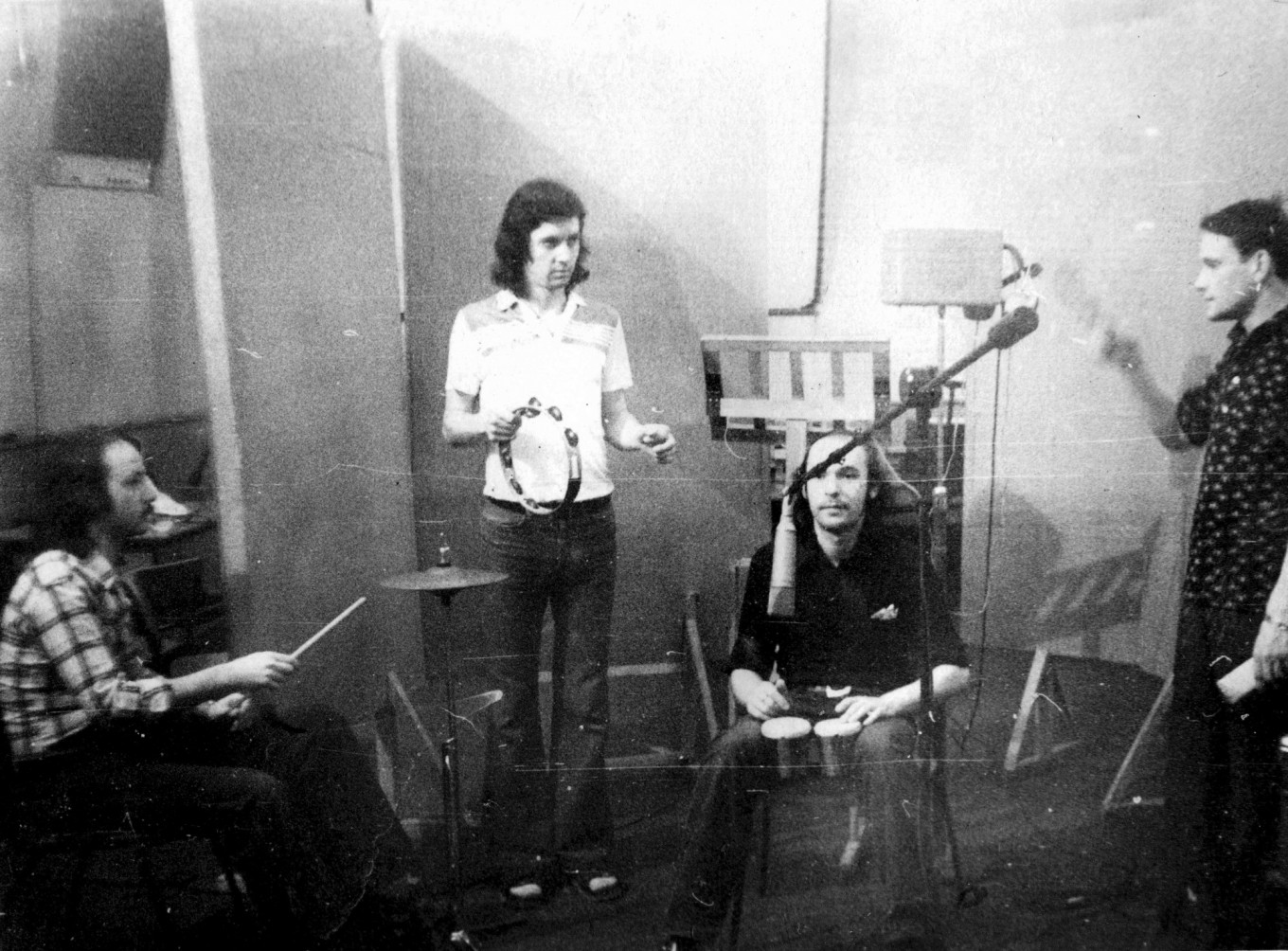

But in 1957, it got a new tenant and a new lease on life. With acoustics the best in the city after the Conservatory, the church was the perfect place for a recording studio. Melodiya Records moved in. They shored up the roof trusses, probably preventing its collapse, and rebuilt some of the buttresses. Here thousands of recordings were made by hundreds of musicians, including such luminaries as Dmitry Shostakovich and Mstislav Rostropovich. They all called the studio the ‘kirche.’

It was also the place where the country’s first rock music was put on vinyl. One of the groups was headed by musician and music impresario Stas Namin, who recalled, “The first project in my life was the group ‘Flowers,’ which became popular nationwide thanks to Melodiya. Almost all our songs for the first 20 years of our existence were recorded in the Melodiya studio, in that ‘kirche’…”

Whose church is it anyway?

When the winds of change began to sweep through the country at the end of the 1980s, religious groups were some of the first people to feel the fresh breeze. In 1991 the Anglican Church was permitted to hold occasional services in the space, and in 1994, spurred by a visit of Queen Elizabeth II, which included attending a service on Vozenesensky Pereulok, the church was given to the Anglican Church association. The church, parsonage and garden were also listed as protected historical landmarks.

But that did not mean that the studio moved out and the altar moved in.

When the Reverend Canon Simon Stephens OBE RN arrived in 1999, the studio was still there. Several years ago, he told The Moscow Times in an interview that even after they were holding services regularly, “it was quite difficult for the clergy and congregation. We had to negotiate the booms and all the other apparatuses required for recording. On Sundays we could use the church, but we had to vacate it every Sunday night, and on Monday morning they wheeled everything back in so artists and musicians could come and record.”

Although the studio eventually moved out, it was August 2016 before the legal complexities were sorted. The church signed at 49-year free use agreement with the federal ministry of property and registered title rights to St. Andrew’s.

But the curious property agreement means that the church community and city both have responsibility to provide funds to restore and maintain the building. In 2018, the church raised $85,000 and the city provided $115,000 to restore one wall. Part of the funds went to do an engineering study of the foundation and roof. When the community raises $350,000, the city will provide up to $2.5 million to complete the work to restore the building.

Jesus Christ Superstar

And that’s where “Jesus Christ Superstar” comes in. Namin said that, considering how much he owed the ‘kirche,’ he was happy to donate a performance of the famous rock opera by Andrew Lloyd Webber and Tim Rice. Their version, performed in English, is the one performed in Jerusalem, and will be the theater’s first show in a church. “I’m delighted,” he said, “to be able to contribute to raising awareness and attracting donations. It’s also a unique opportunity for the cast at Stas Namin Theater.”

Another neighbor, is also helping out: the 8-p.m. Tuesday performance will be preceded by cocktails at 7 p.m. in the church, courtesy of the Marriott Courtyard.

For more information about the event and to purchase a ticket, click on the St. Andrew’s Church site. Donations can be made on the site Just Giving.

In the video below, the city architect Nadezhda Danilenko shows the row of bricks with burn marks indicating that they were taken from buildings that burned in the fire of 1812 and reused inside the structure.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.