This is the last week to see Viktor Pivovarov’s exhibition “Moscow Album” at The Multimedia Art Museum. Pivovarov, alongside pioneering artists such as Ilya Kabakov and Erik Bulatov, was one of the leaders of the Moscow conceptualist movement in the 1970s and 1980s.

A conceptualist is made

Pivovarov, who turned 82 this month, was born in Moscow in 1937. As a boy, during World War II, he was evacuated to Tatarstan, where he claims to have made his first piece of art: a doll made out of scraps of cloth and wood.

“I made myself a doll out of loneliness,” Pivovarov writes in his autobiography, “The Agent in Love.” “And I’m the same now as I was then. The essence of my art hasn’t changed.”

And it hasn’t—loneliness, a focus on the inner life, and a dark sense of humor pervade Pivovarov’s work, which has been displayed in Moscow, St. Petersburg, and Prague with growing frequency since the late 1980s.

Pivovarov’s relatively late start in exhibiting his work can be partially attributed to his roots as a children’s book illustrator, a career path that was popular among Soviet artists. Only in his early thirties did Pivovarov begin painting seriously, surrounded by Moscow’s most talented artists of the time.

“In the history of culture,” Pivovarov writes, “every so often there are periods of explosions, revolutions, years of unusual productivity and an unbelievable concentration of creative energy that artists can latch on to. And in Moscow, this occurred between the years of 1972-1976.”

The focal point of this wave of energy was Sretensky boulevard, which housed the studios of Pivovarov, Ilya Kabakov, Erik Bulatov, Oleg Vassiliev, and Ernst Neizvestny. It was here that Moscow conceptualism, a movement that championed the expression of ideas over form, was born.

At its core, Moscow conceptualism was essentially anti-Soviet: it strove to deconstruct the language of Soviet authorities through irony and absurdity. Pivovarov’s work, however, focused less on social commentary and more on the inner life, art, the artists he associated with, and his beloved home city, Moscow.

During the height of conceptualism, Pivovarov and Kabakov started creating “albums,”—a new genre that combined images and text. The albums often mocked the tone of Soviet advertisements, poking fun at the authorities. One of Pivovarov’s most famous albums, “Projects for a Lonely Person,” gives instructions on how to lead a lonely life. A painting of a desk with a lamp, apple, glass of water, and book is accompanied by text suggesting that a lonely person might use the apple as “a table decoration, a way to eliminate hunger, or a gift for another lonely person.”

Moscow Albums

The exhibition at The Multimedia Art Museum features three of Pivovarov’s albums: the acclaimed “Dramatis Personae” (1996) and the lesser known albums “If “(1995) and “Florence” (2005-2010). The exhibition’s centerpiece is a cycle of new paintings, “Moscow, Moscow,” (2019), which is accompanied by sound installations from audio tapes by philosophers, scientist, writers and poets who influenced Pivovarov.

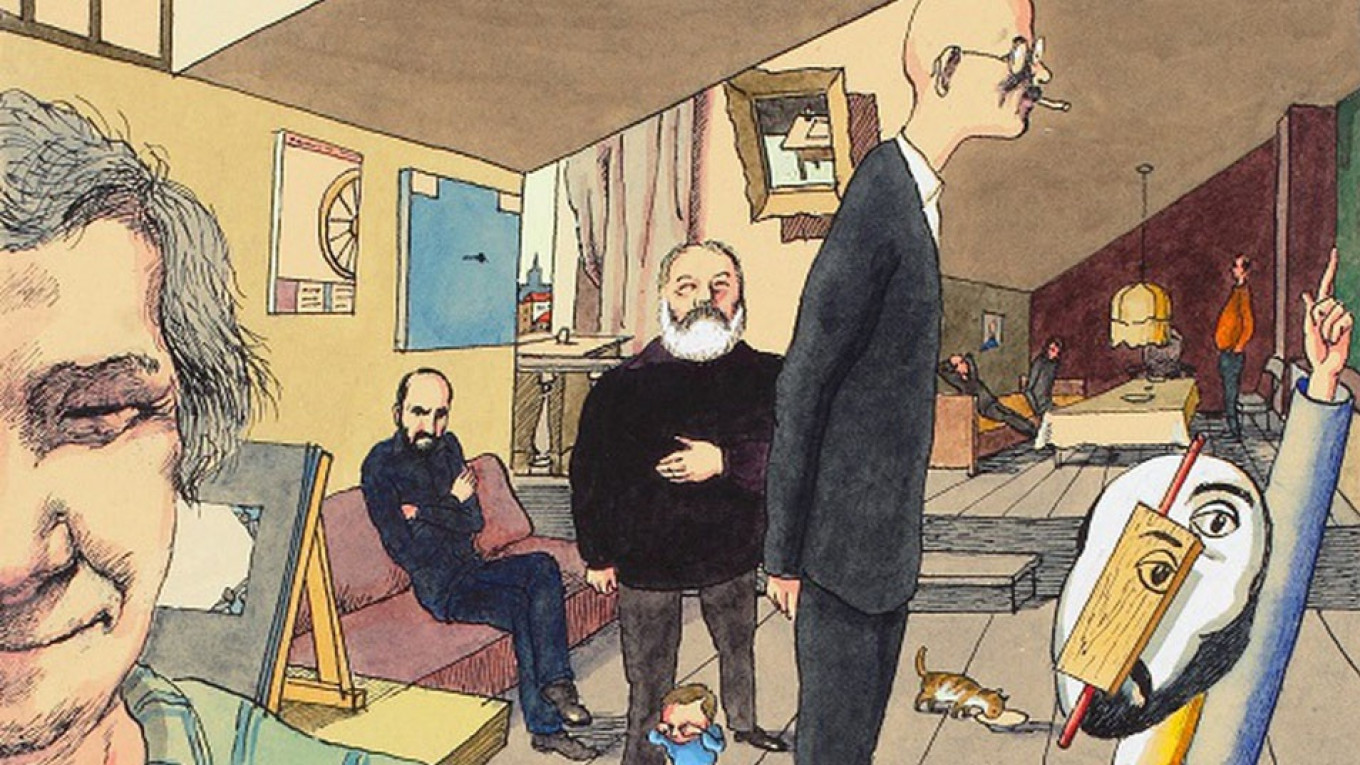

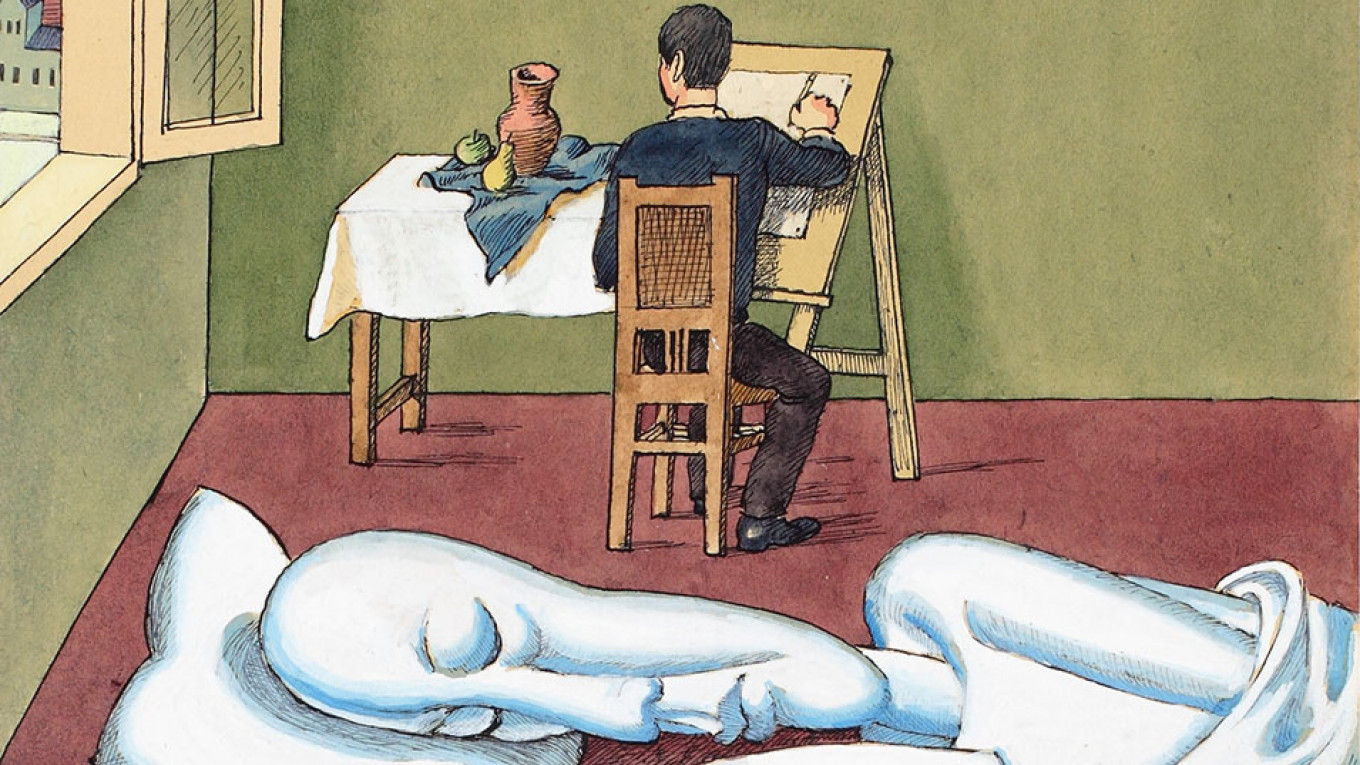

The exhibition begins with “Dramatis Personae,” a series of watercolors depicting the Moscow underground art scene of the 70s and 80s. Parties in artists’ studios, picnics in industrial zones, glimpses into Moscow nighttime windows, and naked women make up the album. In “The Last Existentialist,” a man with one gigantic foot traverses a dark, snowy field, dotted with two tiny houses.

The most conceptual of the albums is “If.” Here there are no images. Instead, Pivovarov presents a series of graphic charts in which he follows several situations to a series of possible conclusions while withholding a definitive outcome. In one of these situations, entitled “If I go to see Natasha and her husband Yura isn’t home,” Pivovarov provides the following possibilities: “If we start to kiss—If we undress—If after we start meeting in secret—If Yura starts to get suspicious—If we have to make decisions—If the fire of passion starts to die—If the only thing that remains is a feeling of cool tenderness.”

Behind a set of curtains, accompanied by the voices of the great thinkers of Pivovarov’s time, is the display of “Moscow, Moscow.” As in his albums, the paintings in this series also combine the serious and the lighthearted, often highlighting the loneliness and absurdity of everyday life. A painting entitled, “A man on a roof wanted to blow his nose but he dropped his handkerchief,” shows a man atop a blue building, his right arm twice the size of his body, watching a huge handkerchief sail towards the sidewalk. The exhibition also features Pivovarov's interpretations of Moscow streetscapes, in which buildings are depicted almost primitively as yellow triangles, silver cylinders and red squares.

“There are stamps of surrealism here,” one visitor said, “but it’s unusual, unlike anything else I’ve seen.”

“Behind every picture is a personal story,” another visitor commented. “I like the exhibition because you can tell that this is an artist who lived in this country, who knows this country, and who has a deeply felt connection to it.”

The show runs through Feb. 3.

16 Ulitsa Ostozhenka. Metro Kropotkinskaya. mamm-mdf.r

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.