When the news broke Sunday night of the theft of a painting at Moscow’s Tretyakov Gallery, it first seemed like a low-tech version of the “The Thomas Crown Affair.”

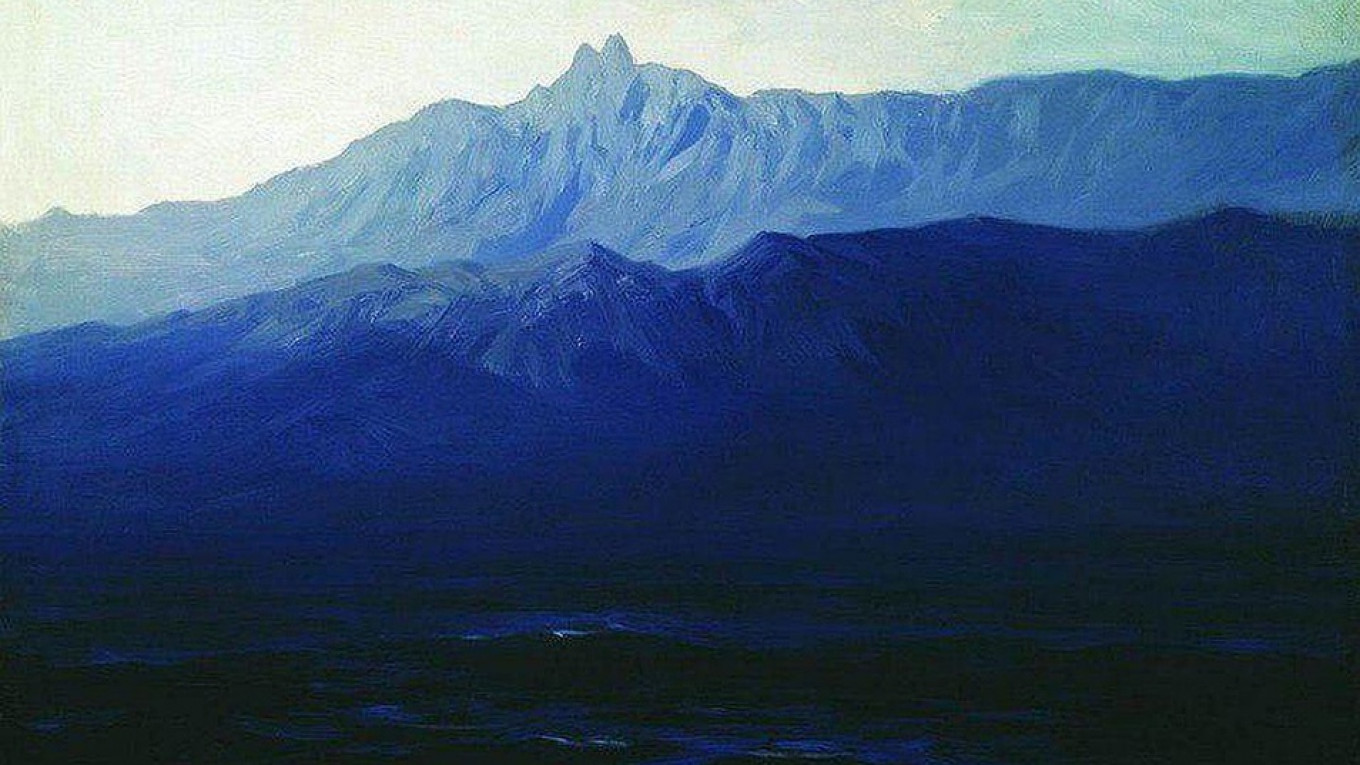

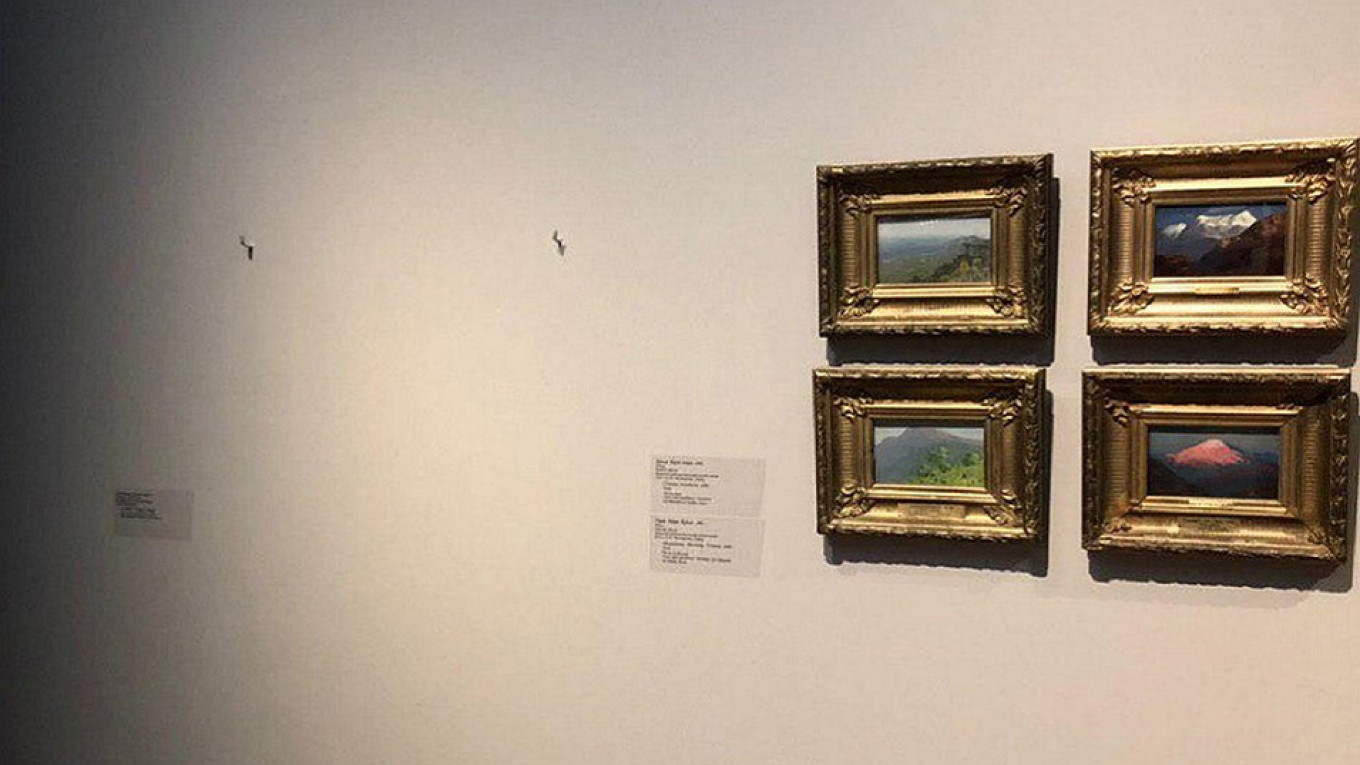

At 6 p.m. on Sunday, in the very popular show of works by 19th-century landscape painter Arkhip Kuindzhi — that is, one of the busiest times and places in the museum — a man coolly walked up to the painting of the mountain Ai-Petri in Crimea, appeared to straighten it, then lifted it off the wall and walked away as if on an errand. In the security tapes, the visitors seemed to assume by his manner that he was a museum worker. A few yards away by a column he popped the painting out of the frame and disappeared through the museum and then out on the street into a waiting Mercedes.

A few minutes after the theft, one of the women attendants sounded the alarm. As it happened, the police were already in the building, summoned over the reported theft of a fur coat in the basement coat-check.

But the story has a happy ending. By the next morning a suspect had been arrested in a town just outside the Moscow city limits. He told the police that he’d stashed the painting at a construction site, and the landscape was quickly recovered. It did not appear to be damaged.

At present, nothing is known about the suspect, other than he was known to the police due to a narcotics charge.

This was not the only incident at the museum in recent months. In May 2017 a man slashed a famous painting by Ilya Repin, “Ivan the Terrible and His Son.” It is currently being restored.

On Monday afternoon at a press conference, the head of the Tretyakov Gallery, Zelfira Tregulova, and two ministry of culture officials were not treating the incident as a caper movie with a happy ending. Tregulova grimly recounted the facts of the theft, noting that the report of a stolen fur coat at the time of the theft was not, she thought “a simple coincidence.” She also said that the painting, which was on loan from the Russian Museum in St. Petersburg, would not be returned to the exhibition at the Tretyakov Gallery but sent back to its home institution.

Tregulova said that the entire approach to museums needed to be rethought. “One of the problems is that museums are more popular than ever and there is a huge number of people who come into our halls every day. Greater access means greater risk. And then we have the image of a museum-goer that was formed in past decades — a person who comes to a museum to look at art.” Now, she said, the public is very different, and the task is to keep the museum accessible while protecting the works.

Vladislav Kononov, director of the museum department of the Ministry of Culture, said that the Ministry was rethinking security at all museums in the country. One of the first measures would be to affix to every work displayed alarms that make a noise or send signal if the art is touched or moved.

Another problem is the different security measures for permanent and temporary exhibitions. Tregulova said that the permanent collection at the Tretyakov Gallery was secured by a number of measures in the halls and on the paintings, but temporary collections were not. “This and every other temporary exhibition will now be secured by alarms on the paintings. The small works of Kuindzhi have already been affixed to the walls and alarms are being put on all the works.”

When asked who was to blame, Tregulova said that she, in the end, was responsible as director of the museum. But she added that, "We are going to check the entire chain of security, determine who was to blame and who didn’t follow instructions. And take measures.”

The Tretyakov Gallery, like other Russian art institutions, has attendants in each hall — generally elderly women who are famous for scolding when a visitor leans to close to a painting, and who keep an eye out for unlicensed tour guides. Tregulova noted the young guards in Western museums and said they’d be considering all the options to update security at both the Old and New Tretyakov Gallery, up to and including checks when people leave the museum “even though people are annoyed by these inconveniences.”

The Kuindzhi exhibition will continue as planned until Feb. 17.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.