One of the must-see shows of the season is the exhibition of works by Mikhail Larionov at the New Tretyakov Gallery. Born in Tiraspol in 1881, Larionov was one of the leaders of the Russian avant-garde. After a brief but significant career in Russia, he emigrated to France with his life-long companion and fellow artist Natalia Goncharova in 1915 and became one of the most celebrated 20th century painters, illustrators, costume and set designers.

Mikhail Larionov started his career at the Moscow School of Painting, Sculpture and Architecture, studying under Isaac Levitan and Valentin Serov. Expelled three times, Larionov had radical views from the very start of his career.

“All that has become established in art depresses me,” he said at the time. “I sense stagnation and it suffocates me… I want to escape from these walls to a boundless space, to find myself in constant motion…”

Breaking with the Russian academic tradition, his early paintings were impressionistic, but after a trip to France, he began to paint in a neo-primitivist style. This was derived, in part, from traditional Russian luboks (colorfully painted storyboards) and the esthetics of commercial signage in the Russian provinces.

In 1908 he was one of the organizers of the Golden Fleece exhibition in Moscow, which exhibited works by avant-garde foreign and local artists such as Marc Chagall, Kazimir Malevich, Claude Matisse, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Gaugin.

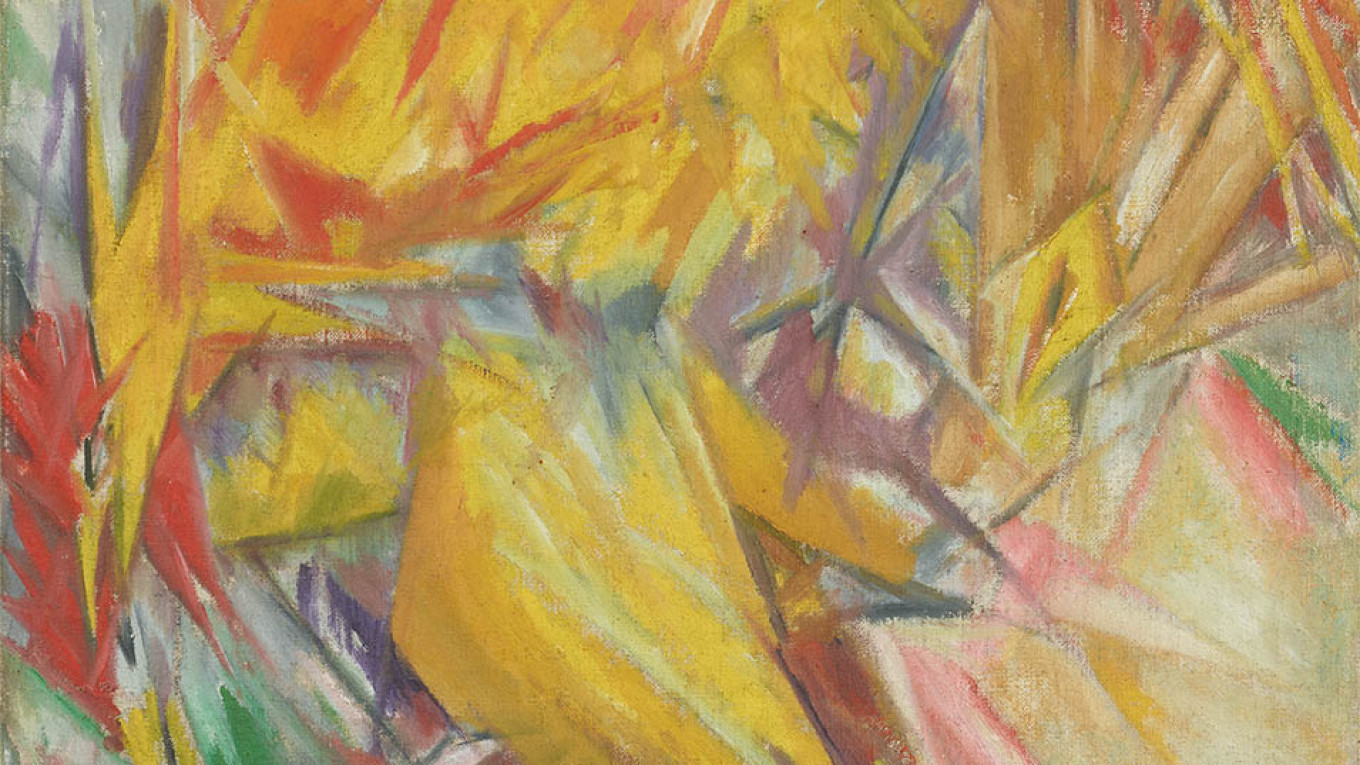

A few years later, in 1913, Larionov invented a new form of art that he called “Rayonism,” which sought to capture on canvas what Larionov said the eye saw: lines of reflected light in rays that were reflected from objects and crossed each other as the objects moved. Although Larionov had been influenced by the Italian Futurists and their representation of movement, Rayonism was Russia’s first home-grown non-representational art form.

Larionov was a founding member of two important Russian artistic groups: the Jack of Diamonds (1909–1911) and the more radical Donkey's Tail (1912–1913). Before emigrating to France, he had one solo show in Moscow, which was held for exactly one day in 1911.

In 1915 he and Goncharova left Russia for what turned out to be the rest of their lives. In Paris they worked with the ballet impresario Sergei Diaghilev on the productions of the Ballets Russes. Larionov spent the rest of his life in France, became a French citizen and divided his time between the seaside in the south of France and the Paris suburb of Fontenay-aux-Roses, where he died at the age of 82.

Apricot trees, peacocks and soldiers

The exhibition, which displays more than 500 works by the artist, begins with an explosion of lush color. Displayed on pale gray, bright blue and yellow walls are Larionov’s earliest work, done from 1902 in the style of impressionism: lush green locust and apricot trees, pink, blue and red houses that were typical during his youth in Tiraspol.

But soon his paintings become more primitive in form and more vibrant in color. “You can find Tahiti in Russia, too,” Goncharova said about his art at that period. He painted scenes of the Russian provinces: cafes, markets, bathers on river banks, as well as turkeys, ducks, dogs and peacocks. Larionov’s series of peacocks showing their magnificent plumage and the glitter of fish scales in daylight bring summer to life.

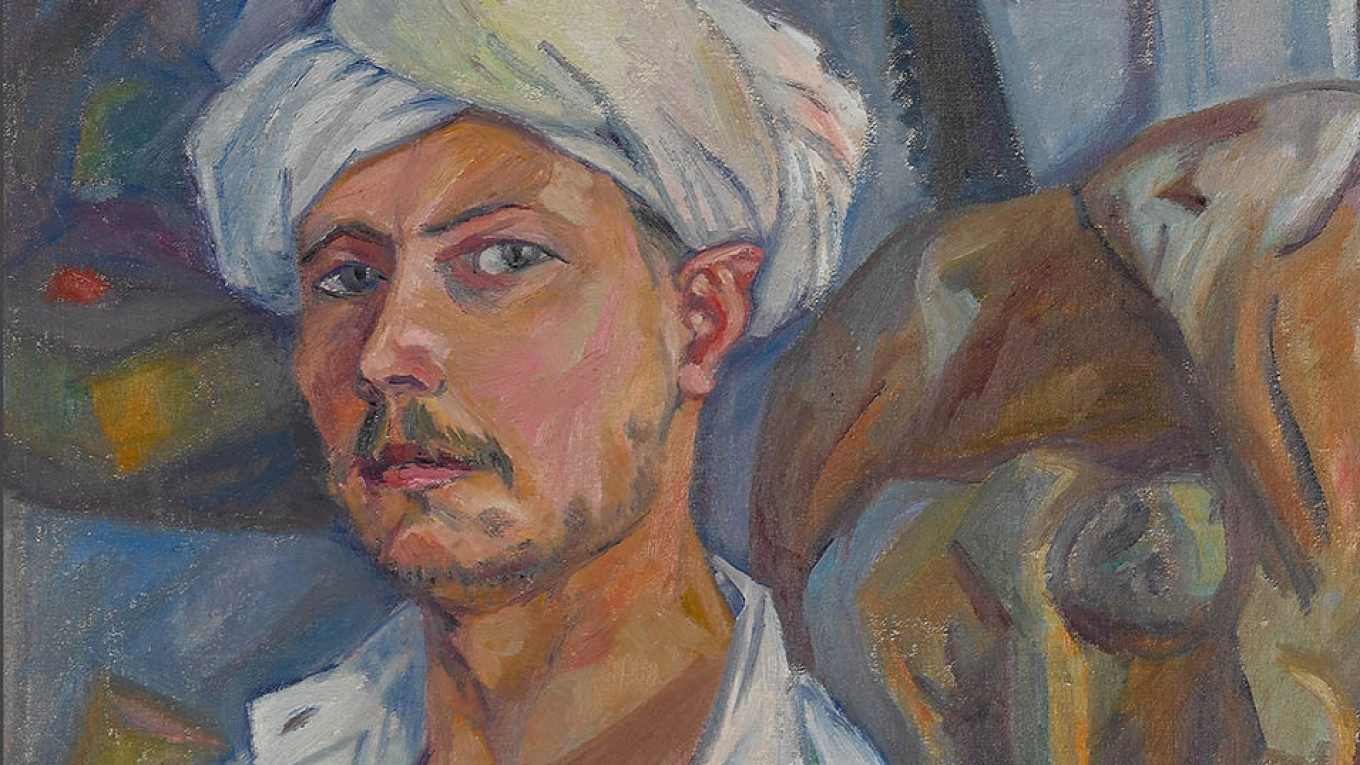

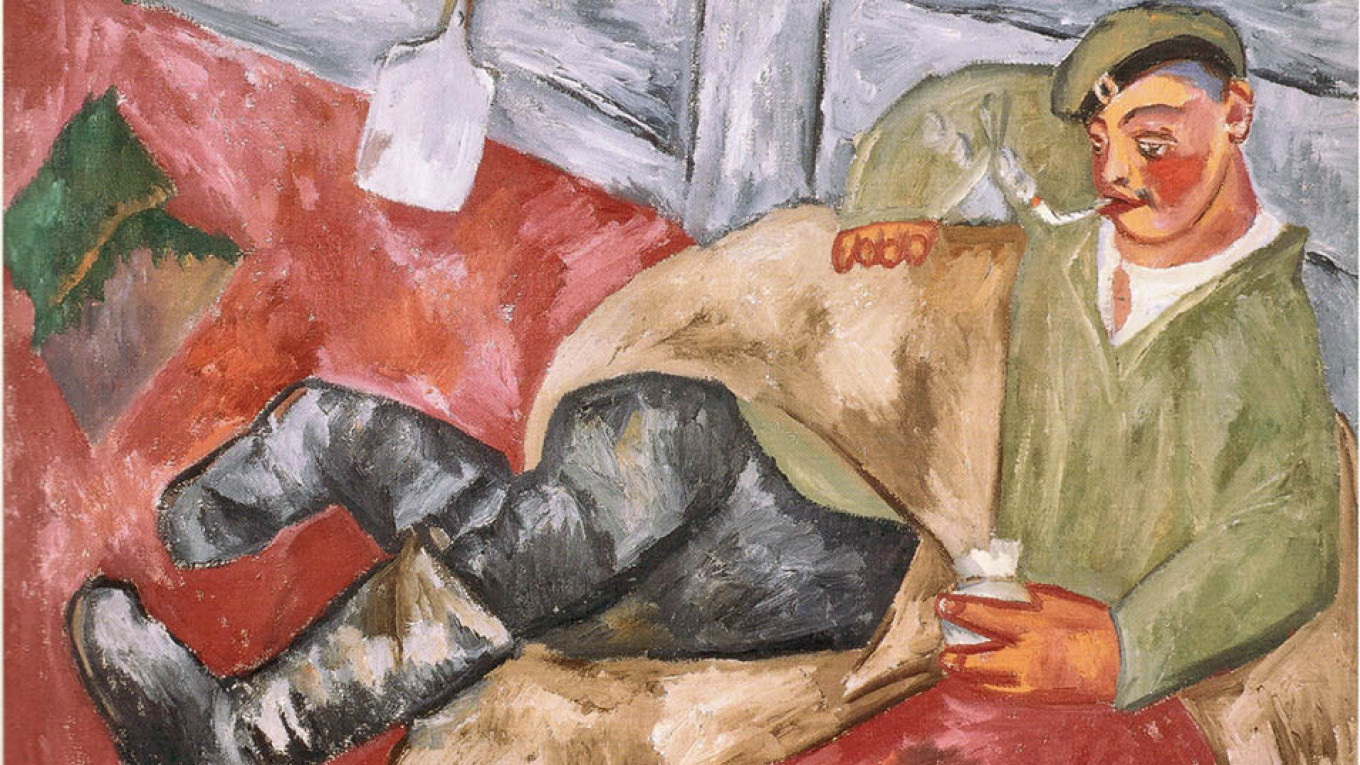

After graduating from the Moscow School of Painting, Larionov spent some time serving in the military. Larionov was inspired by soldiers’ life, but not war and battlefields. He painted life in the barracks and soldiers at rest in such famous works as “Soldier at Rest” (1911), “Soldiers Bathing” (1911) and “Soldier on Horseback” (1911).

Rayonism and the avant-garde

The next section of the show exhibits Larionov’s work as a book illustrator – the artist of hand-made books of poetry by such writers as Velimir Khlebnikov and Alexei Kruchyonkykh – and founder of Rayonism. The Rayonism section features such paintings as “Rayonist Landscape” (1912), and “Bull’s Head” (1912). “Boulevard Venus on a Walk” (1913) shows elements of Futurism in the depiction of movement, while “City at Night: A Rayonist Composition” (1912-14) is non-representative but filled with motion and light.

Throughout his life, Larionov painted “Venuses” – often images of beauty inspired by small-town illustrations. Two beauties, in particular, dominate part of the hall: “Katsap Venus” (from a Ukrainian slang word for Russian) and “Jewish Venus,” both painted in 1912. Larionov continued to paint them throughout his life, including in his famous series of seasons, shown in the next hall.

Diaghilev and life in France

Mikhail Larionov is also famously known as a costume and set designer who worked for The Ballets Russes of Serge Diaghilev. He drew portraits of dancers and choreographers and choreography sketches, as well as sketches for the ballet costumes. Larionov did studies for the costumes for the ballets and choreographic miniatures such as “Soleil de Nuit” (Midnight Sun); “Contes Russes” (Russian Tales); “Chout” (Le Bouffon); and “Le Renard” (Fable about the Fox). These sketches and even a costume from “Chout” are on display.

His later paintings and sketches, many done on the seaside in France, are as pale and devoid of color as his earlier paintings are bursting with it. But his white-on-beige still-lifes, nudes, and seascapes are mesmerizing.

Larionov was also a collector, primarily of books, prints, drawings and anything connected with theater and dance. The last room of the show contains some of his treasures and a wall of his books and journals — yet more color and images to delight the eye.

The exhibition runs until January 20.

New Tretyakov Gallery. 10 Krymsky Val. Metro Park Kultury. tretyakovgallery.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.