For a couple of hours, the reception room in the Embassy of the Netherlands in central Moscow is a microcosm of the world — or at least its female half.

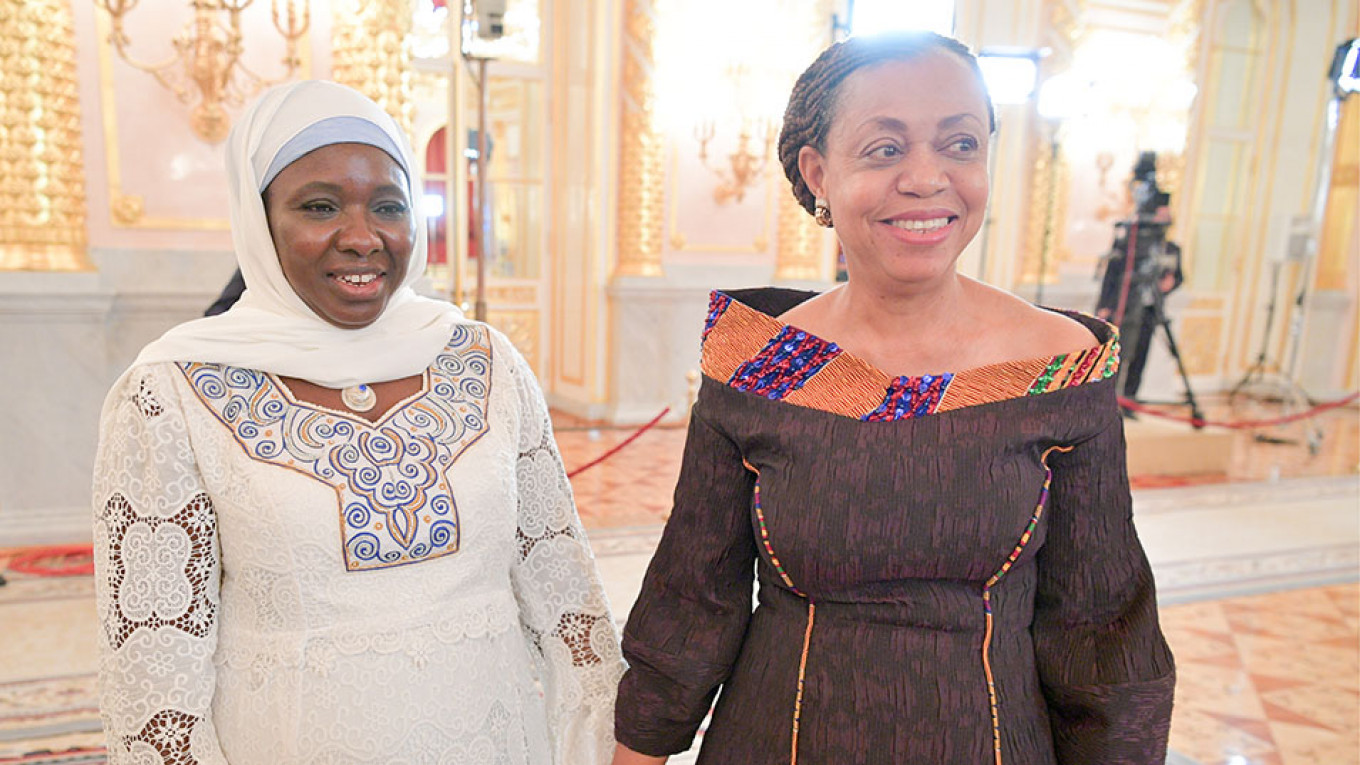

Ghana’s ambassador is wearing a shirt with an orange ruffle collar and her Gambian counterpart dons a silver-embroidered purple headscarf and matching dress. With others, it is their demeanor that betrays their roots.

A petite woman with twinkling eyes gives me a tight hug and a kiss, as if she were my favorite aunt and not the representative of Honduras.

“We women always have plenty to talk about,” declares Dutch Ambassador Renée Jones-Bos a little while later, once everyone has sat down to lunch.

Jones-Bos founded the women ambassadors club shortly after arriving in Moscow in the fall of 2016. The women gather every couple of months to socialize and listen to a guest speaker on a topic of interest. “It’s an informal club, there are no rules,” she says. “It’s mostly about information sharing and support, but of course it’s also fun!”

And fun it is. Someone calls a toast for “our mothers,” and when another confesses she has been married for 30 years, there is applause and even a cheer. For a room full of diplomats, the atmosphere is notably relaxed. Perhaps because this is the most women they have been in a room with since, well, the last reunion.

“There’s no pretense,” Iceland’s Ambassador Berglind Ásgeirsdóttir would tell me later. “There’s nothing to pretend about.”

No newbies here

Of 154 resident foreign ambassadors in Moscow, only 12 are women. Many are the first women to occupy the posts. Their arrival in Russia, a country whose image is one of chest-beating masculinity, signals how far the diplomatic world has come — and how far it still has to go.

Ásgeirsdóttir knows this better than anyone.

Thirty years ago, she was one of two women to be accepted into her country’s foreign service. From there, she went on to become the first female Secretary General of the Social Affairs Ministry and later the Nordic Council. In 2016, she checked yet another “first” box when she was appointed ambassador to Russia.

“This has been happening for so long with me,” she says during a meeting in her office, with a vitality that defies the early hour, (she used to drink 14 cups of coffee per day, she says, but now tries to stick to decaf.) “I’m 63 years old and, again, I am the first woman.”

In part, the gender disbalance mirrors a broader trend of underrepresentation of women in foreign policy, especially in its upper echelons — there are only about 30 female foreign ministers worldwide — which goes back centuries.

“Men were going to foreign lands and women were waiting for them at home,” says Gambian Ambassador Jainaba Bah.

“I think women are considered, with few exceptions, the weaker gender,” adds Norma Bertha Pensado Moreno, the Ambassador of Mexico, which has 28 women ambassadors out of a total 104. In her country's foreign service, women outnumber men at lower levels, she says, “While decision-making posts tend to be more for men.”

Even countries considered pioneers in advancing women’s rights have struggled to buck the trend. In 1980, Iceland got its first woman president, but then took 11 more years to appoint its first woman ambassador. “It’s as if women were advancing in politics and everywhere [else in society], but foreign service was still clearly seen in Iceland as a man’s job!” says Ásgeirsdóttir.

In Russia, however, the gender imbalance in the diplomatic community is glaring.

“Russia is a big power with a strong military-industrial complex,” says Jones-Bos, the Dutch ambassador, by way of explanation. “That is seen as something that men are good at.”

Notably, Jones-Bos and the Ambassador of France — the only two women ambassadors from EU countries in Russia — previously held positions in other United Nations Security Council member states, the United States and China, respectively. (Both as the first women of their countries to take up those posts.)

Some of the ambassadors say they were sent to Moscow with the explicit goal of building bridges, a task maybe seen as more suited to women. “We have to reactivate the relationship, so that’s why we want you to go there,” Pensado Moreno remembers being told.

Ásgeirsdóttir recalls how the prime minister announced her latest appointment in a public speech after the European football championship in France, where she was ambassador at the time, and ahead of the World Cup. The Icelandic team and its fans went on to become widely adored in Russia for their “Viking clap.”

“They call me ‘the football ambassador,’” says Ásgeirsdóttir, with a big smile. “Football, football and fishing technology and a little gender equality every now and then, that’s what I’ve been doing in Russia.”

That proves the rule

Accounting for five of the 12 ambassadors in the group, African countries seem to be doing moderately better. Perhaps, suggests Gambia’s Bah, because since the Cold War, Russia has been seen as a friend rather than a foe there.

“West Africa has long been dominated by Western powers,” she tells me at her embassy, sitting beneath two framed photos: one of President Vladimir Putin, the other of her own country’s President Adama Barrow. “It was Russia which came to help to liberate Africa. It was Russia who named the university after [Congolese independence leader] Patrice Lumumba,” referring to the Moscow institution now known as the People’s Friendship University.

Bah’s passion for Russia goes far back. As a student, she says, she was detained and tortured by intelligence officers of Gambia’s previous government for espousing Communist views. She has named her son Bolshe, after the Bolsheviks.

Women’s role in the struggle for independence has amplified their voices, Bah says, naming Titina Silla and Winnie Mandela as examples. “In Africa women are not seen as weak.”

Who’s the husband?

One of the most noticeable differences with many male diplomats is that the women have personal lives — or, at least, that they admit it. Ásgeirsdóttir, beaming, scrolls through her phone to show off photos of her baby grandson.

It wasn’t always that way. She became a widow when her youngest of three children was only two years old, but kept her private life largely hidden from her colleagues.

“We were so determined to be like the guys, so we never talked about it. Some people didn’t even know I had children,” she says. “Maybe because my generation was working against the glass ceiling every day.”

And while, since then, it has become more accepted for women ambassadors to be open about their offspring, there is still a lingering stigma over their spouses.

“Some younger female colleagues frequently get asked: What does your husband do?” says Mexico’s Pensado Moreno. “But if it were the other way round nobody would ask, ‘What does your wife do?’ because that’s taken for granted. That’s something we have to change.”

Like it or not

Discussing gender with the ambassadors is not without its pitfalls. On one hand, they want to emphasize that their posts are gender blind. Or, as the Dutch ambassador puts it: “There is only one representative to the Netherlands in Russia, and that’s me. Female or male, like it or not.”

On the other, some of their concerns will be recognizable to women in all walks of life.“I really don’t feel very comfortable inviting a male representative from another ministry or company for a drink,” says Pensado Moreno. “You always think: ‘He could misinterpret my invitation.’”

Bah, from Gambia, has found her informal style of leadership has led to some misunderstandings with her staff who, sometimes, can get a little too comfortable. “I feel like they wouldn’t act like that if I were a man,” she says.

Regardless of Russia’s reputation, the ambassadors I spoke to for this article said they had felt welcome and they had not encountered any gender discrimination. In fact, being a woman in a country like Russia also presents a unique opportunity to make yourself seen.

Excited, Bah tells the story of when she went to present her credentials at the Kremlin — a rite of passage for all new ambassadors.

After the official ceremony was over, she got chatting with Russia’s often stone-faced foreign minister, Sergei Lavrov. (“He told me: ‘Your excellency, you look dazzling, you look beautiful.’”) Then, she says, she went over to Putin and gave him a hug. “I don’t think a man would do that,” she chuckles.

Women hold up half the sky

Nevertheless, the women ambassadors insist, their home countries are making progress. Mexico now has special liaisons to advance women’s rights, including one in Moscow. And many countries have made gender equality a central tenet of their foreign policy strategies.

“More than half of the civil servants within the French Quai d’Orsay are women,” French Ambassador Sylvie Bermann says.

Russia, too, is taking steps, the ambassadors say, pointing to the government’s national strategy plan for women and its hosting of the second Eurasian Women’s Forum in September in St. Petersburg — attended by Putin — as positive developments. “It’s a step in the right direction, which also opens space for more cooperation between our two countries,” says Bermann.

But Russia could still learn from other countries. “I have noticed that gender equality works very well until the first child is born,” says Ásgeirsdóttir. “Then women often start to cut down on their careers.” She notes Iceland’s law on parental rights, where both men and women each get three months of non-transferrable leave and three more months to divide among them.

Russia also has only one woman ambassador, in Indonesia, despite owning the bragging rights to having appointed the first ever female ambassador, Alexandra Kollontai, in 1923.

Ultimately, at a time when international relations with Russia are fraught, appointing more women ambassadors could be a bet on peace, some of the ambassadors suggest.

“Women are not only often the first victims of armed conflicts around the world; they are also part of the solution,” says Bermann. “In this sense, I hope that [being a woman] is an advantage in this period of tense relations between the EU and Russia.”

"I am not a supporter of a 'feminist diplomacy' but I believe it is important to have a just and equal representation of the society within our system. Indeed, as the Chinese say, 'Women hold up half the sky,'" she adds.

“Women are mothers, wives, this is embedded in our biology and it’s in the way we were raised,” agrees Bah. “Women assess the consequences, we have a more holistic picture.” On my way out of her office, I get a big hug.

A version of this article appeared in our special "Women in Focus" print issue. For more in the series, click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.