The annual meeting of descendants of Lev Tolstoy recently took place at the writer’s familial estate, Yasnaya Polyana. More than 100 people came from all over the world to participate in this traditional gathering of one of the world’s most illustrious literary families. The descendants meet every summer to ride horses, drink tea and talk about their great ancestor.

Marta doesn’t look like she belongs at Yasnaya Polyana. She has an Italian last name — Albertini — and looks like a true daughter of Italy. She lives in Orvieto, a small Italian town about 100 kilometers from Rome. But she is, in fact, a great-granddaughter of Lev Tolstoy. One of the writer's daughters, Tatyana, married Mikhail Sukhotin and gave birth to another Tatyana, Marta's mother. “My mother was brought up practically without a father, because my grandmother married a widower,” Marta said in an interview with The Moscow Times.

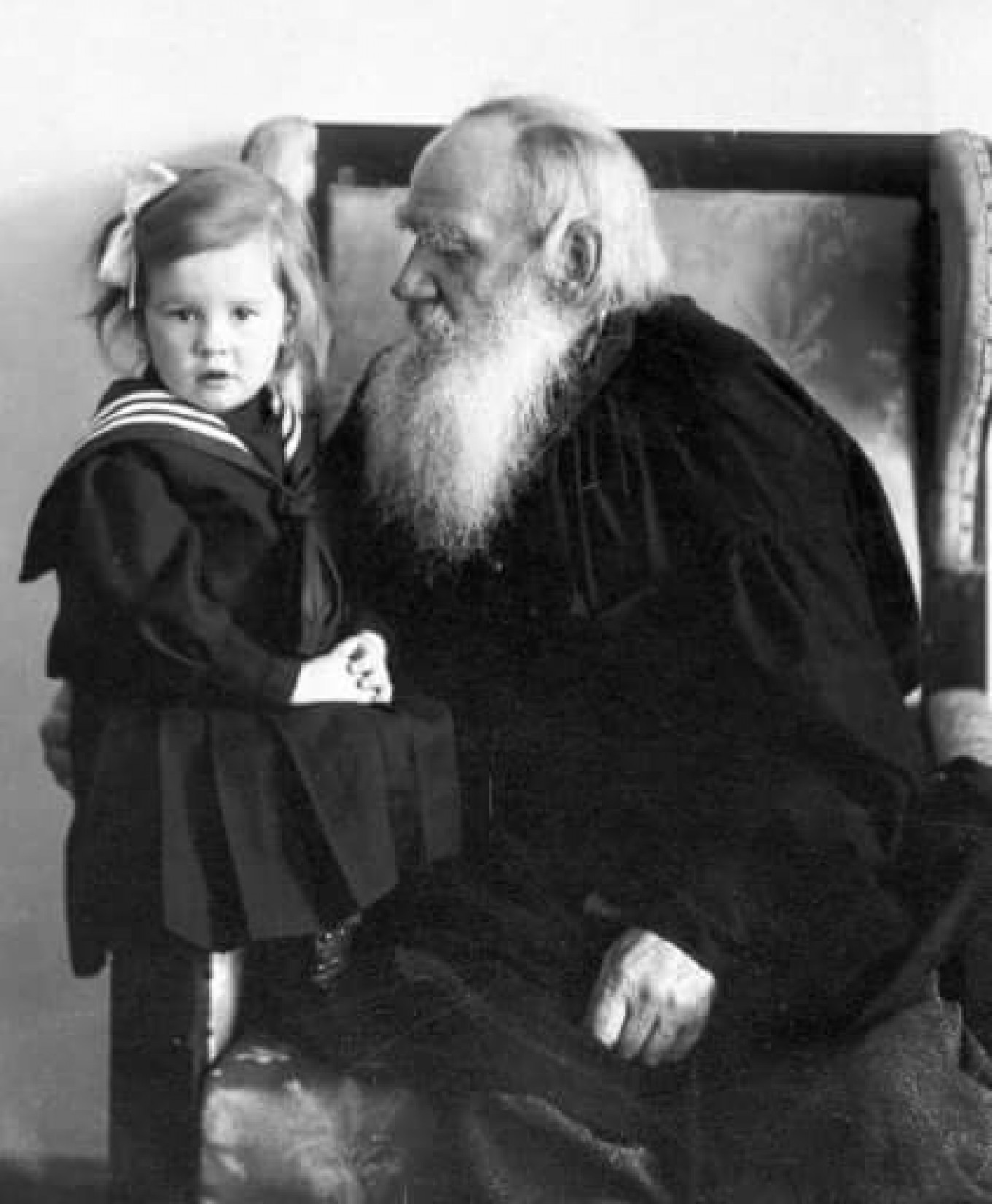

“Sukhotin was twenty years older than Tatyana Tolstaya, but it was really a marriage of love. Lev Tolstoy was against this marriage, because he was always jealous of his daughters. He was not an easy person. But the couple got married in 1899 and Sukhotin died of a heart attack in 1914. In fifteen years she had five stillborn children because of an incompatibility of blood type. My mother was born in 1905, and she was always called ‘l’enfant du miracle.’ She soaked up this adoration. There are so many photos of her with Lev Nikolayevich [Tolstoy]. She was really very beloved.”

Marta has been coming to Yasnaya Polyana for decades. “At one point Russia was a country that was just there. But nobody [from my family] would visit it. We never went to Russia. Then my mother received an invitation from the U.S.S.R. Ministry of Culture and came to visit in early 1970s with my brother. She went for several more visits, and I came with her in 1979.”

By that time Marta was already 42 years old. “It was a shock. I felt Italian, even though I knew that there was this other half of me in my blood. I don’t exactly know what I felt. I didn’t feel Russian at all. I felt more French. We went to Yasnaya Polyana and I saw Tolstoy’s grave for the first time and, of course, it made a great impression on me. And the countryside, all those woods — it’s so big! But of course, we weren’t free to move around, so it was a bit difficult.”

A book of letters

Marta is a writer herself, she’s currently working on a book devoted to her mother and grandmother with the working title of “Tatyana and Tanya Through Letters.”

It all began with the discovery of a suitcase full of letters addressed to her mother, Tatyana. “They were hidden away for so many years. There were no stamps because I think my mother used to give me and my brother these letters when we were sick to play with, and we tore off the stamps. I asked my brother and sister whether they would allow me to do something with these letters because I realized how precious they were. They agreed.”

The letters were from other Tolstoys, including Sophia Tolstaya-Yesenina — another granddaughter of Lev Tolstoy and the wife of poet Sergei Yesenin — cousins and other more distant relatives. “The letters are from 1925, the year my mother and grandmother left Russia, until 1930, when my mother married my father, Leonardo Albertini. And then there are no more letters. I don’t know why. Maybe she didn’t keep them or kept them in another place.”

The most moving, in Marta's opinion, are the letters between her mother and Sophia Tolstaya-Yesenina. “She was my mother’s beloved friend. Sophia was five years older and my mother was really fascinated with her. My mother sent Sophia the poems she wrote, influenced by Anna Akhmatova. In one of the letters, she writes to Sophia “love me” five times in a row. I think that at the time, love was their food.”

Marta was taking her time with the book. “Fyokla Tolstaya [Tolstoy’s great-great-granddaughter and deputy director of the Tolstoy Museum in Moscow] came to visit and celebrate my 80th birthday. I told her about the book and she said, “Why don’t you come to Moscow?” I said, “Yes, but...” She told me, “No buts!”

A diary lost and found

Marta's trip to Moscow led to another discovery: At the archives of the Tolstoy Museum she found her mother’s diary. “Fyokla was upset that no one knew the diary even existed and at the same time happy that we found it. She said, ‘If you hadn’t come, we never would have found this diary.’”

Tatyana Sukhotina’s diary covers the events between 1917 and 1921. “She started it when she was just 12 and finished when she was 16 years old. These are the most important years for a girl, especially in those times,” said Marta.

The dairies are filled with information about life in Yasnaya Polyana. In 1918 Tatyana Sukhotina wrote, “Today an airplane landed in Yasnaya Polyana and Grandmother invited the visitors in for tea. Then they wanted to see Tolstoy’s grave and took pictures. It was fascinating to see the airplane move.” But she was still a little girl. “Then we came home and I played with some paper dolls that my mother made.”

While Marta's book still has a long way to go until publication, excerpts from Sukhotina's diaries have already been published online by the Arzamas project.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.