Among the things that will likely strike a visitor to Odessa are the busy seaport (the largest in Ukraine) and the gloriously crumbling 19th century architecture. Stay a little longer, and its cultural past begins to reveal itself in the monuments plentifully scattered throughout the city. But you could spend years here and never come across one of Odessa’s most unlikely curiosities, an English-language magazine called The Odessa Review.

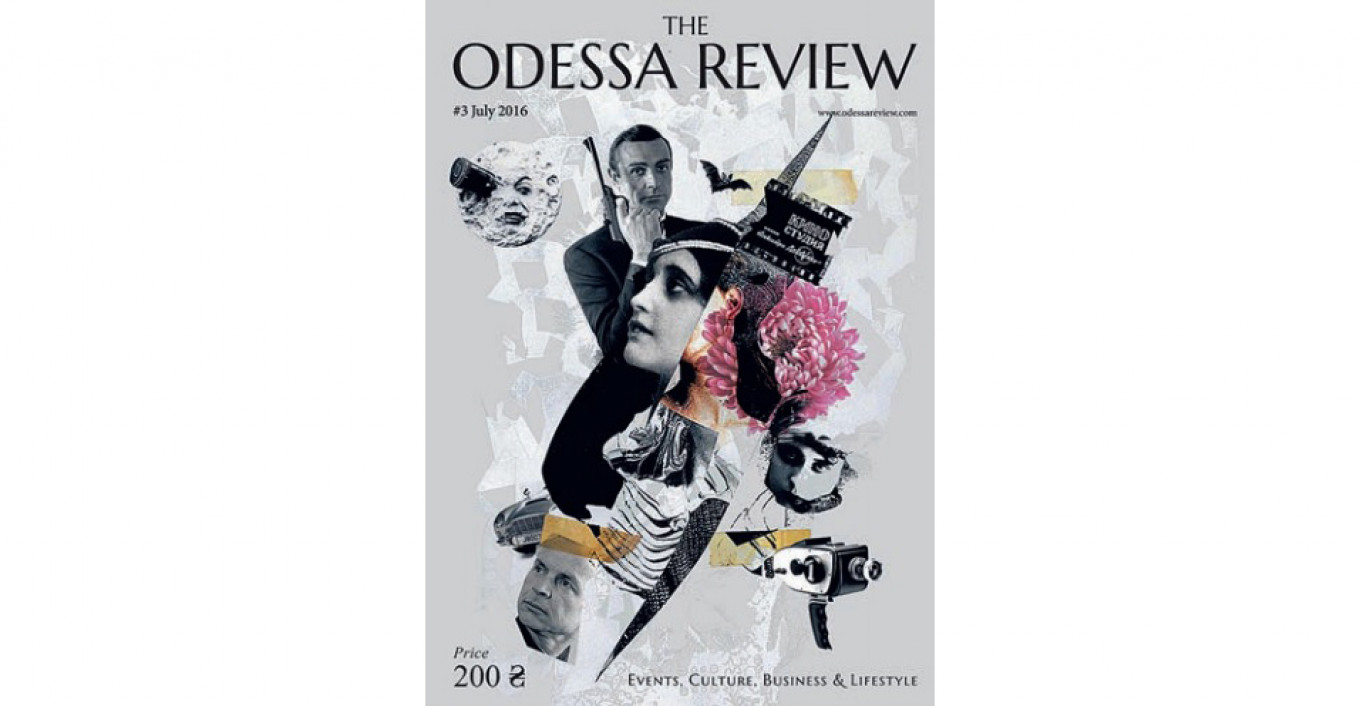

Finding this bimonthly publication, a literary journal emulating The New Yorker and The Paris Review, is not easy. You’ll have to hunt it down at one of just a handful of locations in Odessa and Kiev. Once you open the cover, however, you will be rewarded with up-to-date and relevant coverage of issues related to contemporary Ukraine and the region.

A literary entrepreneur

The magazine’s chief editor is Vladislav Davidzon. Now in his early 30s, he was born in Uzbekistan to Russian-Jewish parents and moved to New York’s Brighton Beach, also known as “Little Odessa,” when he was seven years old. While he grew up in the United States, he spoke Russian at home and learned about Russian literature from his grandmother, who he describes as a “literatus and art connoisseur.” Thanks to his upbringing, he never lost touch with his Russian roots. He describes himself as “very deeply devoted to this part of the world” and “deeply Russian.”

In his early 20s he made the decision that he would move to eastern Europe. After graduating from The City University of New York with a double major in Slavic studies and philosophy, he met his future wife, Odessa native Regina Maryanovska, while studying at the Sorbonne in Paris. From there they moved to Venice, where Davidzon received a master’s degree in human rights law, and from there to Ukraine, where he became a journalist for “Ukraine Today,” a now defunct English-language Ukrainian television station.

Davidzon and his wife started The Odessa Review in 2016. “I always wanted to have my own magazine, a literary journal,” Davidzon said. “No one’s done this before. No one’s ever had the ludicrous idea to have a Western-language, New Yorker-style literary journal of ideas in this region. It’s too weird.”

Chronicling the golden age

Where Odessa natives tend to be modest about the potential of their city, Davidzon gets visibly excited when talking about the cultural opportunities in Odessa. He says that Ukrainian culture is now seeing a “golden age.”

The Odessa Review has been riding this new wave of Ukrainian culture, providing commentary and reviews of events, literature and phenomena happening in Odessa and elsewhere in Ukraine. It often frames its coverage in terms of the idea of a contemporary Ukraine, constantly returning to themes of the Ukrainian nation and identity. After Maidan, the annexation of Crimea and the war in Donbass, it is almost impossible to have a political conversation in Ukraine without touching on what it means to be Ukrainian. That question is especially fraught in Odessa, a city of Russian-speakers where many identify more closely with Russia, and where 46 locals were killed in a fire in 2014 while protesting Maidan.

“We’re a product of post-Maidan Ukraine,” Davidzon told The Moscow Times. The Review supports liberal viewpoints regarding Ukrainian independence and territorial sovereignty, but there is no agreed upon doctrine for liberal-minded Ukrainians to follow. The Review often functions as a forum for starkly dissonant responses. For example, in an issue devoted to Ukrainian Jewry, the Jewish-Ukrainian journalist Vitaly Portnikov argued that a Jewish community is impossible in the Ukrainian nation, and that “if you identify primarily as a Jew and that is more valuable to you, do not delude yourself, go to Israel.” A few pages later Vitaly Chernovianenko, a history professor, argued that “Jewish Studies need to become part of an integrated humanities culture and educational system in Ukraine.”

Davidzon has built a large network of contributors to the magazine, and many of the pieces are by some of the region’s leading experts and cultural figures. The Review has published articles by journalist Peter Pomerantsev, historian Timothy Snyder and poets Boris Khersonsky and Adam Kirsch. Many of the bylines are also from young Ukrainian journalists who Davidzon has helped to mentor, introducing them to concepts of journalism that are not included in the standard Ukrainian curriculum. “There’s not a school of Western-style journalism,” he explained. “Not one person in Ukraine makes a living as an art critic or a book critic or a film critic.”

Connecting Odessa to the West

Locals are hesitant about their city’s status as a cultural center, still shell-shocked after mass emigration in the 1990s. Where Davidzon sees a cultural revolution, others still see room for improvement. The curator of Odessa’s Museum of Modern Art, Alexandra Troyanova, was positive about the amount of interest that the arts have been getting lately, but uncertain whether there were any young artists to match the growing demand. The art critic Ute Kilter, who contributes to the Review, echoed this sentiment, saying “It’s very complicated for contemporary art to exist in Odessa. Kiev eats all the money, which is why [The Odessa Review] is so important to us. This way there will be at least something.”

That the journal is in English is crucial to its mission. Boris Khersonsky, a poet who lives in Odessa and regularly publishes in the Review, explained that “it is the only thread connecting Odessa with the English-speaking world.”

One piece Davidzon was particularly proud to have published was an excerpt from Sergei Loiko’s novel “Airport,” which was widely praised in Ukraine but had not before appeared in English. It is a portrait of the battle for Donetsk’s airport as told by one soldier. For foreigners who are not familiar with the war in the Donbass, it is crucial reading.

The print circulation for each issue is currently around 10,000. They also have a website, where they track 60 percent of their traffic to North America. To grow their readership, Davidzon and Maryanovska-Davidzon want to expand coverage to other parts of the Black Sea region. In addition, they plan to host events in the future, which they hope will bring more attention.

Davidzon points out another benefit to learning more about the city: “I think more people would come here if they knew how great it was and how inexpensive it was. Why wouldn’t anyone want to come to Odessa?”

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.