Russian opposition leader Alexei Navalny is taking on the Kremlin once again. But this time, he has competition.

The anti-corruption blogger isn’t the only opposition force trying to rally protests against the government’s highly contentious decision to raise the pension age. As paradoxical as it might sound his main opponent is the Federation of Independent Trade Unions of Russia, which is controlled by the same authorities who are implementing the unpopular move.

Anywhere else, this might be considered political schizophrenia. But not in Russia. Here, when launching an unpopular policy (more than 80 percent of respondents to recent polls are against the changes to the pensions system), the state is prepared to temper its original plans depending on how disgruntled people are. The Russian authorities have roused the otherwise dormant trade unions to lead the protest that will allow them to gauge dissent.

For the government, the number one priority is that President Vladimir Putin’s ratings do not suffer and that he does not have to take responsibility for any of this. What seems most likely is that he will enter the fray last of all, and meet the people halfway by softening the current plan.

Raising the retirement age to 65 from 60 for men by 2028, and to 63 from 55 for women by 2034, is not, incidentally, even really a reform. It is merely an attempt to bring pensions in line with the demographic trend of an aging population (not to mention the fact that no other country with comparable levels of income has such a low retirement age). It also reflects a desire to save some state money.

The problem is that in order to live happily long beyond the retirement age — a great age by Russian standards — you have to be healthy. This is not something which older Russians are known for. On average, people live just over 10 years after retiring, according to various estimates.

And to work longer, people need education and the opportunity to switch professions. But there is no tradition in Russia of lifelong learning. Despite the low official unemployment rate, many Russians have difficulty finding a job or normal salaries once they are over the age of 45-50.

Not to mention that it was these same authorities who canceled the real pension reform they had begun — to transition from a distributive system to a funded one — having supposedly frozen those funds. But actually, they had sunk them into annexing Crimea.

Russians’ outrage over the proposals has of course been seized upon by politicians (including parliamentary deputies, who will feign well-managed discontent), opposition parties and trade unions (which sociologists have found to be extremely unpopular) and opposition activists.

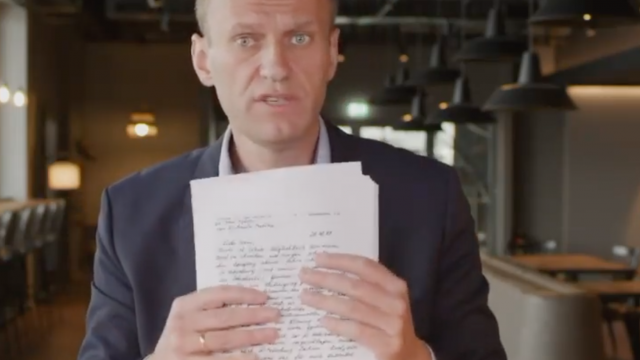

There is no way Navalny would pass up an opportunity like this. He is barred from appearing on state media and he cannot take part in elections because of a hotly contested criminal conviction. Like any politician, he is using any chance he gets.

The question is only whether he will become the leader of the protests or just an element of them. While a majority of Russians have been angered by the move, far from all of them are Navalny supporters.

It would actually have made more sense for Navalny to protest against the government’s other proposal, increasing VAT, since that measure will hit economically active Russians, including entrepreneurs and consumers. To protest that proposal would have made it possible to attract a younger and better-educated section of the population, which largely tends to trust Navalny. But the politician probably reasons that that would narrow his protest audience somewhat.

The crux of the matter is not even the actual content of the reforms, but the fact that any initiative that issues from the state is met with distrust. Yes, most people support Putin (but to a lesser extent in recent weeks) — as a symbol of greatness synonymous with the Russian flag — but that does not increase the level of trust in the state. Russians believe their politicians will swindle them at every opportunity.

It is this utter lack of trust in the state that Navalny is looking to exploit. Ultimately, as an opposition figurehead, he has far more right to do so than the under-the-thumb trade unions and parties. They are merely feigning protest.

Andrei Kolesnikov is a senior associate and the chair of the Russian Domestic Politics and Political Institutions Program at the Carnegie Moscow Center. The views expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.