Alexei Bakhrushin was widely known in early 20th century Moscow for his collection of theater objects. With over 1.5 million individual items, ranging from entire costumes to ordinary paper fans, his collection is probably best described as a "hoard."

Large though it may be, the collection is filled with treasures that tell the story of Russian theater from pagan times all the way to the golden years of the late empire. Leading our tour of the Bakhrushin Theater Museum was the excellent Katya Provornaya, the museum’s digital curator.

The museum is located in Bakhrushin’s former house, an eclectic red and white brick mansion across the Garden Ring from Paveletsky Station. It was designed specially for him by the architect Karl Gippius, who did not restrain his imagination or desire to impress his client. The main entrance hall, where we began our tour, is worth visiting just for the beautiful staircase and giant stained-glass window, echoing an English Gothic castle. Here we learned a little about Bakhrushin and his collection, which raised a few eyebrows at the time for its unconventionality; more than a few Muscovites considered it a pile of junk!

The items on display are picked from the collection and displayed to give a grand tour of Russia’s history of theater overall, with a special emphasis on Bakhrushin’s own time period. Everything has a story to tell here, and Katya picked out a few of the 1.5 million items to focus on.

One particularly remarkable display is a collection of small telescope-like tubes that tell us a wonderful story about the theater culture of the time. One function of these tubes is as opera glasses, which are, interestingly, labelled “male” and “female.” Thankfully, this does not refer to anatomy, but rather to the secret function they perform. The female tubes have a compartment for salt, which, at the right moment of a play, a woman would apply to her eyes to induce tears; the desired effect was that her neighbors would be amazed at how sensitive she was. The male tubes also had a social function. A man would inhale the powder from his tube, take aim at the nearest attractive woman, and sneeze. If he didn’t immediately scare her away, it would provide an opportunity to start a conversation.

The second half of the tour was focused on the temporary exhibition “Two Centuries of Marius Petipa.” Katya told us the story of Petipa, who started off as a second-rate dancer in Europe and moved to Russia with the help of his brother, who was much more famous at the time. In St. Petersburg, Petipa worked with many of the great composers of the day, including Pyotr Tchaikovsky, to create some of the world’s most recognized ballets, including“Swan Lake,” “The Nutcracker” and “La Bayadere.”

If the first half of the display showed Russian theater from a macro lens, here we were given the opportunity to peer into the intimate life of one ballet company, and the world of Petipa. His company was seen as a tight-knit club (rather like a reality TV show), with a defined set of characters. On the wall we can see caricatures of the main cast, depicting each member with her flaws and defining features. These gems were created by the Legat brothers, who were choreographers and followers of Petipa. Among the characters, there were rivalries and love affairs, friends and enemies.

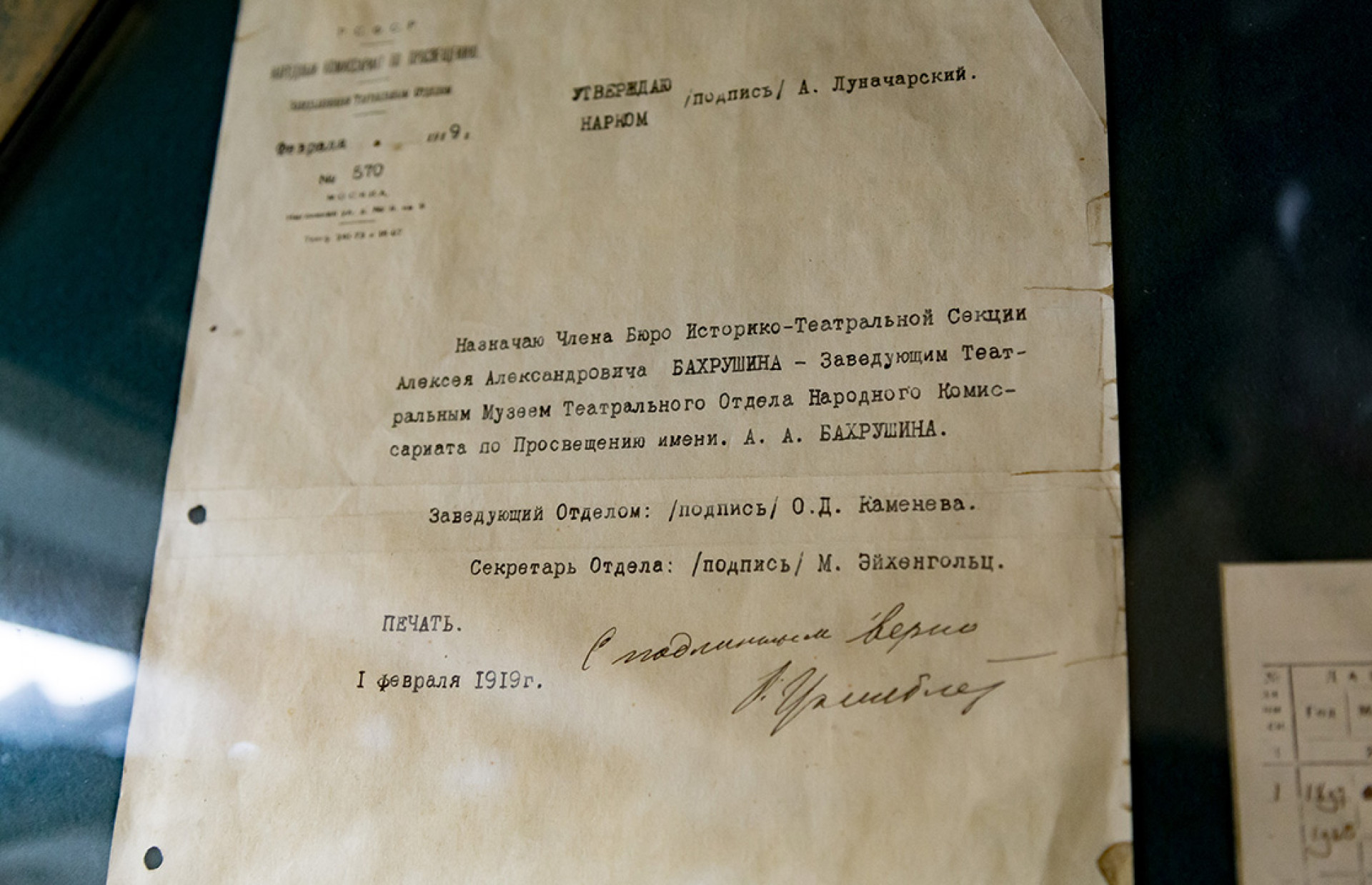

One of the portraits is a less-than-flattering depiction of Mathilde Kschessinska, the mistress of Tsar Nicholas II and the subject of the controversial 2017 film “Mathilde.” She is shown with beady eyes, wide-spaced teeth, awkwardly long arms, and a goat trailing behind her. Petipa, in his diaries, notably called her a pig. When she found out she was not going to have a lead role in “Pearl,” she convinced a powerful friend to intervene on her behalf, which he successfully accomplished. On an adjacent wall, a document shows the names of the entire cast for one ballet,with a number next to each name. The number, Katya explained, was the amount of sweets each dancer would receive for a successful performance, in pounds. In the top spot was Kschessinska, where a three had been crossed out, replaced by a four.

From the exhibition, we headed through the museum’s garden into a giant constructivist building, now empty, which was given to the museum last year and is sometimes used for temporary exhibitions. Here champagne and hors d'oeuvres awaited us, as we discussed what we had learned from the exhibition and participated in a small quiz with prizes.

This visit was organized by The Moscow Times' clubs.

To get more information on events and sign up, click here. Or follow us on Facebook!

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.