Background

No trip to Yekaterinburg would be complete without a trip to the Yeltsin Center, a social, cultural and educational space named after one of the city’s most famous sons.

The Yeltsin Center opened in Yekaterinburg at the end of 2015 and quickly became one of the must-see sights in the city. The center is funded by the Boris Yeltsin Presidential Center, a non-profit devoted to “promoting the development of the institute of the presidency in Russia.” The organization seeks to educate visitors on the history of Russia in the 1990s and also celebrate the country’s move to democracy and freedom.

Though Yeltsin himself was not born in the city but in a village in the surrounding Sverdlovsk region, he is associated with Yekaterinburg in the minds of most Russians. In 1976 he became the first secretary of the Communist Party’s regional committee, which roughly corresponded to the position of regional governor. Yeltsin served in this position until 1985, when he was transferred to Moscow; he went on to become Russia’s first president.

The Yeltsin Center is part of Yekaterinburg City, a development in the City Pond area, which was started in the 1980s when Yeltsin himself ran the city. He ordered the construction of the city’s TV tower skyscraper , jokingly referred to by locals as “the party member.” The main investor in Yekaterinburg City is UGMK (Ural Mining and Metallurgical Company) and just three new buildings have been completed so far, ranging in height from 21 to 52 floors. Adjacent to the Demidov skyscraper, the Yeltsin Center cost 7 billion rubles ($113 million), almost 4 billion of which was provided by the federal government. It was designed by Ralph Appelbaum Associates, one of the largest and oldest architectural firms in the U.S. The firm specializes in museum design, and was also commissioned for Bill Clinton’s presidential library in Little Rock, Arkansas.

Exploring the center

The Yeltsin Center is much more than just a history museum; it also functions as a cultural and public space. The complex is enormous and boasts a contemporary art gallery, an independent bookstore that doubles as an education center, a theater, a concert hall, several shops and restaurants, and even a nightclub. There’s something going on every day of the week: a lecture, a film screening, a concert or an exhibition opening.

The museum’s permanent exhibition has courted controversy, as it depicts the “turbulent 1990s” as a time of true democracy, implying that the current Russian leadership does not quite provide that. It also glosses over some of the less appealing aspects of Yeltsin’s rule, such as the war in Chechnya and the president’s battle with alcohol.

The opening hall in the center is called “Labyrinth,” and it tells the Yeltsin family story within the framework of 20th century history, starting with the 1917 October Revolution and moving on to Yeltsin’s rise within the ranks of the Communist Party, including his time as party boss in the Sverdlovsk region and the impact he had on Yekaterinburg.

The rest of the museum is devoted to the events of the 1990s, when Yeltsin was Russia’s president. It is located on the second floor and rather pompously named “Seven Days that Changed Russia.” There are seven sections, all located around a circle. The fi rst is called “I Want Changes” (named after a well-known song by rock band Kino) and is devoted to perestroika and the fi nal years of the Soviet Union, when Yeltsin was the mayor of Moscow.

“August Coup d’Etat” is about the 1991 coup, which saw Yeltsin rise to power, while “Unpopular Measures” is devoted to the shock economy of the early 1990s. “Birth of a Constitution” talks about the adoption of the 1993 Russian Constitution and “Vote or Lose” discusses the controversial 1996 elections. “Presidential Marathon” is devoted to Yeltsin’s second term and fi nally, “Farewell to the Kremlin” talks about the difficult decision to resign and hand power to Vladimir Putin. At this point, the flow of history seems to simply stop; the museum doesn’t touch the Putin era.

The reconstructed reality of the early 1990s, like the neon-lit empty store shelves fi lled with huge cans of birch juice, is easily recognizable and instructive for younger Russians who didn’t live through it. Among other highlights is a replica of Yeltsin’s apartment in Moscow on the day of the August 19 coup d’etat, with the TV playing “Swan Lake” on a loop, just as it did that morning, and a life-size trolleybus that Yeltsin used to take during his days in Moscow City Hall. There’s also a meticulously restored replica of Yeltsin’s office in the Kremlin.

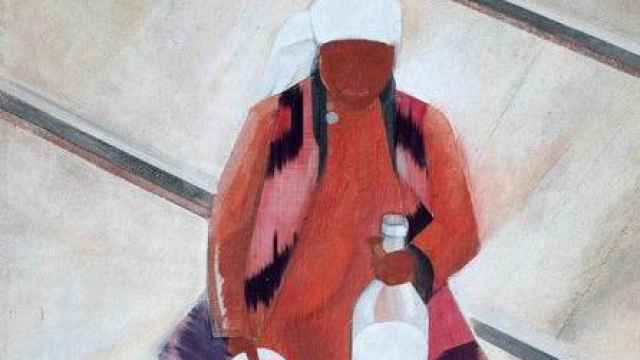

The final hall is called “Freedom Gallery,” and the exhibition talks about civil rights and freedoms in the new Russia. The painting “Freedom” by Erik Bulatov is here, as well as quotes from Russia’s dissident poets and writers, There’s also a statue of Yeltsin sitting on a bench, where one can take a selfie with the first president.

OPEN daily 10 a.m. to 9 p.m., closed Monday

TICKETS 200 rubles

Ulitsa Borisa Yeltsina, 3 yeltsin.ru

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.