Founded in 1723, Yekaterinburg is Russia’s fourth-largest city, with a fascinating history and plenty to keep curious visitors occupied.

Just like St. Petersburg to the north, Yekaterinburg was founded by Peter the Great. If St. Petersburg was a “window to Europe,” then Yekaterinburg was planned as a “window to Asia.”

The first human settlements appeared in the area around 8,000 B.C., but it was only in the early 17th century that it officially became Russian territory; in the latter half of the 17th century, a village was founded near Lake Shartash.

If St. Petersburg was a “window to Europe,” then Yekaterinburg was planned as a “window to Asia.”

In 1720, Peter the Great sent his emissary Vasily Tatishchev to oversee mining factories in the Urals. Tatishchev quickly antagonized the Demidovs, a family of influential industrialists, and was replaced by a German, Wilhelm de Gennin. Tatishchev and Gennin are considered Yekaterinburg’s founding fathers and a statue of the two stands in the very heart of the city.

Yekaterinburg’s official founding year is 1723, when the new iron factory opened on the bank of Iset River. The town was named after Catherine I, Peter the Great’s wife, who became Russia’s first empress after her husband’s death.

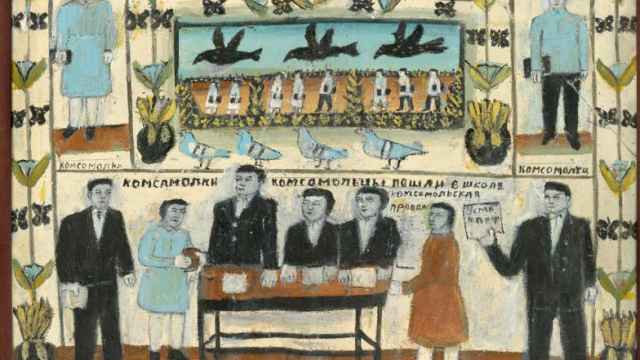

Yekaterinburg gradually became a center of mining and metalworks. By the end of the 19th century, it was also an important railway junction. Yekaterinburg was one of the first cities to accept the October Revolution in 1917, but the city changed hands several times during the Russian Civil War.

Yekaterinburg became a major evacuation center during World War II and this solidified the city’s status as the industrial capital of the Urals.

In April 1918 Tsar Nicholas II and his family were moved to Yekaterinburg by the Bolsheviks. They stayed in a house in the center of the city, which formerly belonged to the Ipatiev merchant family. The basement of that house was where the tsar and his family were executed in July 1918. The Ipatiev House was demolished in 1977 and the Church on the Blood was built on the site in the early 2000s and is now a major place of pilgrimage.

In 1923 Yekaterinburg became the capital of the newly established Ural region and in 1924 the city was renamed Sverdlovsk after prominent Bolshevik Yakov Sverdlov, who fell ill and died in 1919. Sverdlov spent time living in the city but he also had another connection with Yekaterinburg: He signed the tsar’s death sentence.

During World War II, Yekaterinburg became a major evacuation center, and more than 50 factories were moved there from the western territories of the Soviet Union. This solidified the city’s status as the industrial capital of the Urals. In 1967 the city’s population reached 1 million people.

In 1976 Boris Yeltsin became the first secretary of the Sverdlovsk Region Committee of the Communist Party. Yeltsin stayed in the position until 1985, when he went on to serve on Moscow’s Committee and eventually became Russia’s first president. Sverdlovsk was renamed Yekaterinburg in 1991, but the surrounding region is still called Sverdlovsk region.

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, a deep economic recession led to chaos in Yekaterinburg. A gang war ensued, with several organized crime groups fighting for control of Uralmash. In the 2000s the city made a recovery and its economy continues to perform relatively well. Yekaterinburg is now the fourth-largest city in Russia, with a population of almost 1.5 million.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.