They are the children of the 2000s, the digitally savvy youth who were reared on social media and came of age online. They have also only known life under one president, Vladimir Putin. We might as well call them Generation P.

The 1.3 million Russians born in 2000, the year that Putin first became president, and after are difficult to pin down, analysts say. On one hand, Russia’s relative wealth and comfort have created a generation that is both self-righteous and apathetic, says Natalya Zorkaya, head of socio-political research at the Levada Center, an independent pollster. “They are Putin’s self-satisfied and smug youth,” she says.

On the other hand, they were on the front lines of anti-Kremlin rallies that swept the country last year. “This generation has little in common with the regime,” says Yelena Omelchenko, who runs a youth research center at the St. Petersburg Higher School of Economics.

Now that Putin has won an overwhelming victory in the March elections, extending his rule to 2024, who are Generation P and what role will Russia’s youth play in the next six years and beyond?

Break with the past

In 2005, Putin famously described the collapse of the Soviet Union as the “greatest geopolitical catastrophe of the century.” While not all Russians agree, few would dispute that the Soviet collapse brought turbulence and uncertainty. Crime skyrocketed and poverty and unemployment hit almost every Russian family.

But it was also a time of unprecedented freedom, including in the media and politics. And almost three decades later, luxuries that were unattainable for most Russians in the Soviet Union, like holidays abroad, the latest gadgets and freedom of movement, have become features of everyday life for Generation P.

“The previous generation grew up in a world that was only just opening up,” says Vasily Gatov, a Russian media analyst. “For the new generation, the doors were already wide open.”

Generation P appears to be embracing this post-Soviet Russia. They have prioritized getting ahead in education and their careers, Omelchenko told The Moscow Times. “They have moved away from the collectivism of previous generations to a more individualistic approach,” she says.

They are also overwhelmingly conservative. According to a survey published in December by Levada, young Russians are the group most averse to change. “The youth today don’t vote,” says Zorkaya. “They prefer to preserve the status quo.”

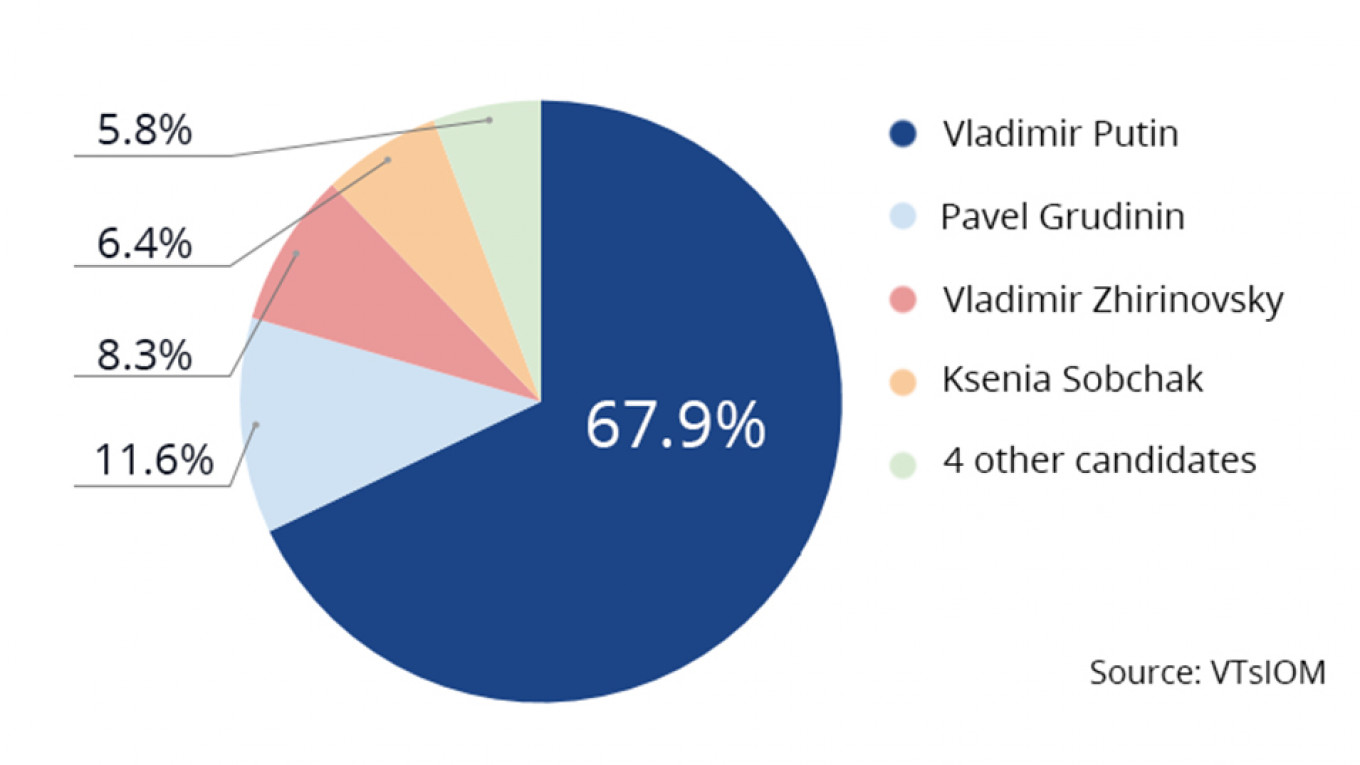

Those who did go to the polls in March voted overwhelmingly for more of the same, an exit poll by the state-funded VTsIOM pollster suggests. Almost 70 percent of respondents aged 18 to 34 cast their ballot for Putin.

In the same poll, the former reality television host Ksenia Sobchak, who at 36 was the youngest candidate and ran on an anti-establishment platform, won just 6 percent.

YouTube generation

This reluctance to change can be traced, in part, to the crackdown that followed mass anti-Kremlin protests in Moscow in 2011-12, says Zorkaya, when dozens of young Russians were detained and handed heavy prison sentences. “The protesters realized their helplessness in the battle against political power,” she says. “They were disturbed and discouraged.”

After that, Russia’s youth mostly lay dormant until a wave of anti-government demonstrations led by opposition leader Alexei Navalny erupted last year. Young Russians climbed lamp posts and were at the forefront of the protests, chanting slogans like “Corruption is stealing our future.” Photos of riot police violently detaining them flooded social media.

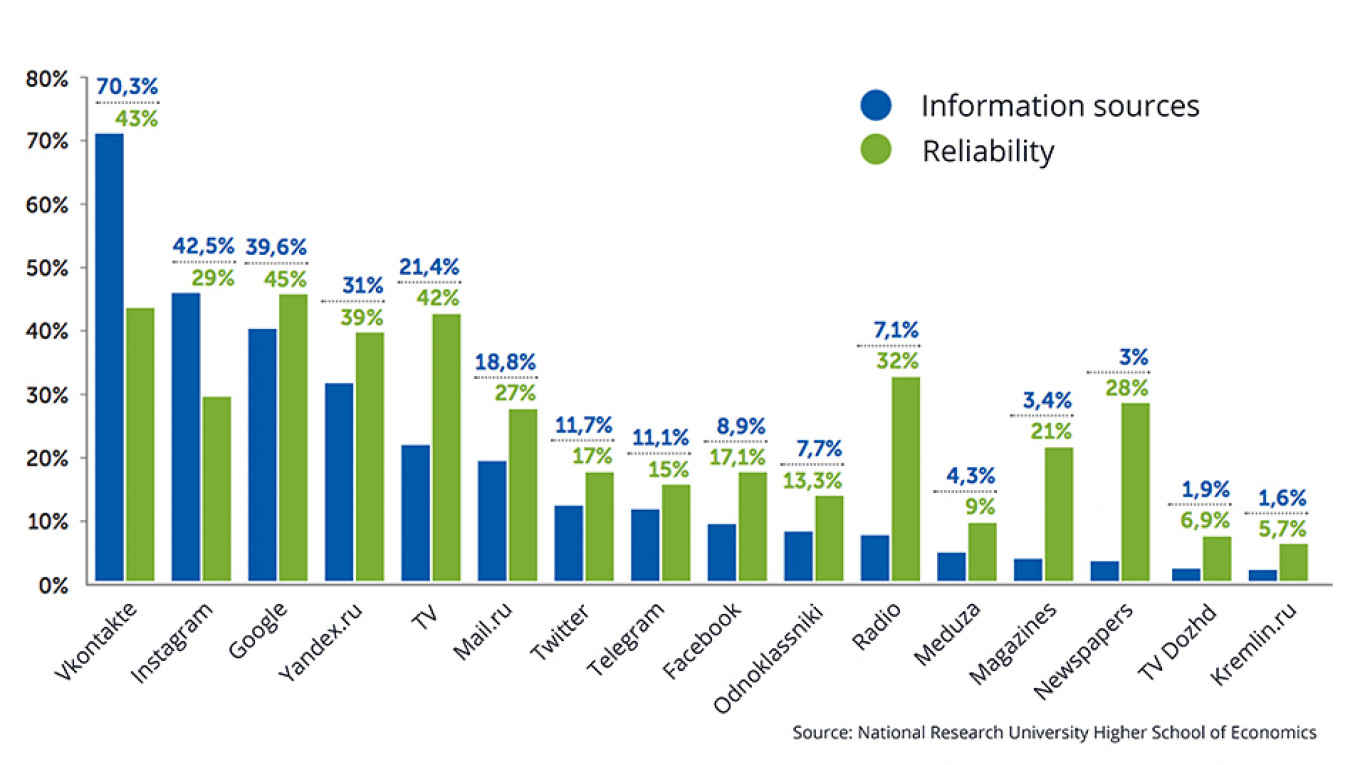

One explanation for Generation P’s protest potential is their immunity to state propaganda, says Gatov, the media analyst: “The internet is their natural habitat.” (Notably, it was a video posted by Navalny on YouTube that eventually led to the protests.)

Russian teenagers participating in the rallies also seemed unafraid of possible repercussions. “Going to protests is a physical activity with elements of risk, something more attractive for the younger generations,” says political scientist Yekaterina Schulmann.

Kremlin-run news outlets and state officials suggested Navalny had used the internet to manipulate young people onto the streets. Presidential spokesman Dmitry Peskov even said that they had been promised cash.

But teenagers interviewed by The Moscow Times at an election boycott rally this year painted a different picture. The protests, they said, allowed them to express their frustration at the lack of momentum in Russia. “Putin has been president for longer than we’ve been alive,” said Nastia, 15.

Echoing the sentiment widely heard in pro-Kremlin circles, Margarita Fadeicheva, who runs the state-funded publication Our Youth, says Navalny’s protests have nothing to do with politics. “It’s just hype,” she says. “They protest for the imaginary popularity they get online.

But the online space has also provided young people with a different means of political participation. “Youngsters who watched the live coverage of the protest automatically became part of it, without being physically present,” says Schulmann.

Kremlin’s youth

Pro-Kremlin youth is mobilizing, too. After the 2011-12 protests, groups like Nashi, a modern-day take on the Soviet-era Komsomol, and Lev Protiv, which aggressively fights smoking in public, were part of a government-led effort to create an army of politically active youth.

The Kremlin has also funded patriotic youth forums such as the famous Seliger camp, which Putin and other high-ranking officials have made a point of visiting.

They target young Russians who have a sensitive spot for Putin’s brand of conservative nationalism and feel the need to defend Russian values. In a study by the Higher School of Economics, 68 percent of students said Russia’s survival depends on its status as a great power. “We call it ‘offended patriotism,’” says Omelchenko.

Members of these groups are not necessarily staunch supporters of Putin personally, researchers add. Pro-Kremlin activism might also be just a way of climbing the social and professional ladder. “These groups are formed under the wing of the power elite of Russia,” says Omelchenko. “They know that their activism will be rewarded and will boost their professional careers.”

Because pro-Kremlin youth groups are not grassroots, “they’ll continue to exist as long as they are given official attention,” adds Schulmann. “When they don’t get any, these groups vanish.”

Role models

With only a small group of young Russians taking part in anti-government demonstrations, and pro-Kremlin groups having little effect on the overall political landscape, why is the Kremlin concerned with Generation P at all?

Mostly, the Kremlin’s attention is symbolic, says Schulmann: “Politicians want to create a sense of closeness to younger generations.” But “the current regime doesn’t understand that it is not the desires of the youth that need to be discussed, but how to share power with them,” says Gatov.

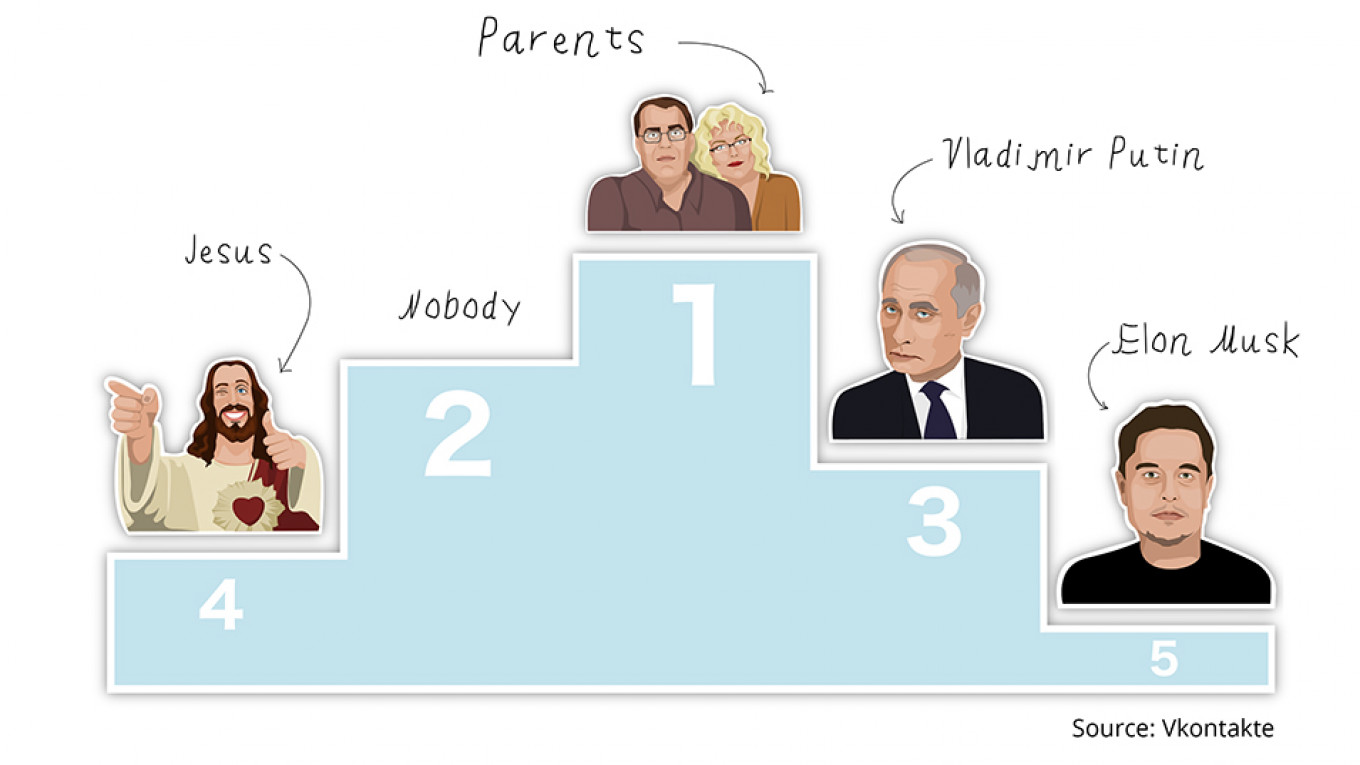

Young Russians need a leader closer to their own age, someone who is more relatable, he suggests. “Someone like Pavel Durov,” the co-founder of the Vkontakte social network and the Telegram messaging service which was recently banned by the Russian authorities.

Ultimately, Generation P’s impact on Russia over Putin’s next term depends on whether it can organize coordinated action, says Zorkaya. “Otherwise, they are doomed to fail.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.