How did Russia, a relatively poor country on the fringe of Europe, manage to amass one of the world’s best collections of European art?

The answer is simple: thanks to its private collectors.

Russia’s first great collector was Empress Catherine the Great, who purchased a private collection of art from a German merchant in 1764 and began to add buildings on to the Winter Palace to house it. Now the collection, amounting to more than three million works of art, is known as the Hermitage Museum.

But many of the Hermitage’s most famous works came to Russia thanks to the great 19th century Russian collectors of art.

The Great Collectors

In Moscow, two brothers, Sergei and Pavel Tretyakov, began to use profits from the family’s textile trade to collect paintings by Russian and European masters. In 1892, Pavel donated the collection, largely of Russian art, to the city of Moscow. Today the Tretyakov Gallery is the greatest museum of Russian art in the world.

Meanwhile in another part of Moscow Sergei Shchukin and Ivan Morozov were collecting European artists. Shchukin was a textile merchant whose obsession with art seems to have begun in 1897 with his first trip to Paris. He brought back a work called “Lilacs in the Sun” by Claude Monet. Within a few years he bought another 13 paintings by Monet, and then almost 40 paintings by Henri Matisse, as well as canvases by Paul Gauguin, Vincent Van Gogh and Paul Cezanne. While other collectors laughed at him, he was the first collector to appreciate Pablo Picasso and brought over 50 works back to Moscow. By the time of the 1917 Revolution, Shchukin had gathered the finest and most prescient collection of impressionist and post-impressionist works in the world.

Ivan Morozov was another Moscow merchant who fell in love with French art, particularly the impressionists and their successors. His favorite painter was Cezanne, although he brought works by Renoir, Pissarro, Bonnard and many others to Moscow.

The 1917 Revolution forced both collectors to emigrate from Russia, and their collections were expropriated by the state. First the government repurposed Schukin’s mansion into the State Museum of New Western Art to house the works of both collectors. But the collections were eventually divided up among state museums — primarily the Hermitage in St. Petersburg and the Pushkin Museum of Fine Arts in Moscow.

Continuing the Tradition

During the Soviet era, purchasing art from artists or individuals directly, outside official galleries or state commission stores, was illegal. Threat of imprisonment did not, however, stop collectors, who furtively acquired art works and hid them in their apartments. Only after the dissolution of the Soviet Union did some of these collectors come out of their rich closets. To house these extraordinary collections and honor the men and women who gathered them, the Pushkin Museum dedicated a new building, the Museum of Private Collections.

Throughout the 1990s and into the next century, Russian oligarchs — successors, in some ways, to the rich merchants and industrialists of the 19th century — began to follow the national tradition.

Perhaps the best known and most successful new collector and patron of the arts is the oil tycoon Roman Abramovich, who has channeled millions into new cultural establishments, like the remodeled New Holland Island in St. Petersburg and the Garage Museum of Contemporary Art in Moscow.

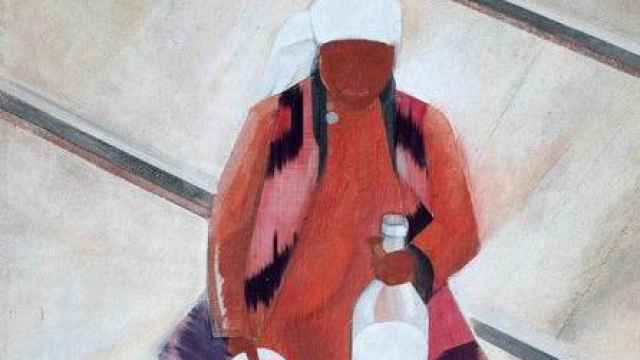

The Museum of Russian Impressionism, opened in 2016 in an impeccably repurposed confection factory, was founded by Boris Mints, owner of the investment holding company O1 Group. About 15 years ago he began to seriously collect the work of Russian impressionist artists. Now his collection, and the stylish space and adjacent business center, is a welcome addition to the Moscow art scene.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.