The hot Moscow exhibition that's got people lining up outside of the Pushkin Museum in the December cold is “Peredvizhniki and Impressionists: On the Way to the 20th Century.”

The exhibition explores parallels between two schools of painting and is a rare chance to see jewels from both the Pushkin Museum's famous impressionist collection and the Tretyakov Gallery's comprehensive peredvizhniki collection in one place.

While the impressionists don't need an introduction, you might not know about the peredvizhniki, sometimes called “The Wanderers” or “The Itinerants.” This was a group of Russian realist painters who opposed the restrictions of academic art.

The exhibition consists of about 80 pieces, arguably the best art works of each school. You can see Edouard Manet's paintings alongside works by Ilya Repin and Vladimir Makovsky, Alfred Sisley side by side with Alexey Savrasov, Valentin Serov with Pablo Picasso and Nikolai Yaroshenko with Pierre-Auguste Renoir.

Irina A. Antonova, the President of the Pushkin Museum and the person behind the exhibition's concept, said in an interview with The Moscow Times that “the peredvizhniki and impressionists are the two largest schools of painting both in terms of their creative output and their reflections on the state of art in the latter half of the 19th century.”

Different Societies, Different Movements — But Surprising Commonalities

The idea of the exhibition came out of research by a famous Russian art history scholar, Nina Dmitriyeva (1917–2003), who examined Russian art within the global context. In her article “Peredvizhniki and Impressionists” she reflected on how two schools of art with different philosophies appeared at about the same time in Russia and France, and how — despite their differences — they had much in common.

Both schools were in opposition to official strictures of academic art. Fourteen peredvizhniki quit the Academy of Arts in St. Petersburg and then founded the Society for Traveling Art Exhibitions in 1870. The first impressionist exhibitions were derided by critics and laughed at by society.

Both peredvizhniki and impressionists lived by new principles, above all — the depiction of real life. Quotidian subjects, like workers in a field or people picnicking in a park, became acceptable in this new paradigm. “So in ‘Olympia’ Edouard Manet painted a real woman in real surroundings rather than Venus or Danae or some other character from mythology or Christianity,” Antonova said. Manet is often called the founding father of modernism for this transition to realism. He started working within the confines of the old system, just as peredvizhniki had all came out of the Academy of Arts.

Of course, French society at the time was very different from Russian. “By the second half of the 19th century France had gone through several revolutions while Russia had just abolished serfdom, so it's clear that our countries were not at the same starting point,” Antonova said. Yet in the world of art, both Russia and France moved towards realism.

The French and Russian art worlds were well connected in the 19th century. Ilya Repin, Vasily Polenov and other peredvizhniki regularly went to study in France, sometimes working in Paris for three years at the time.

The Art That Followed

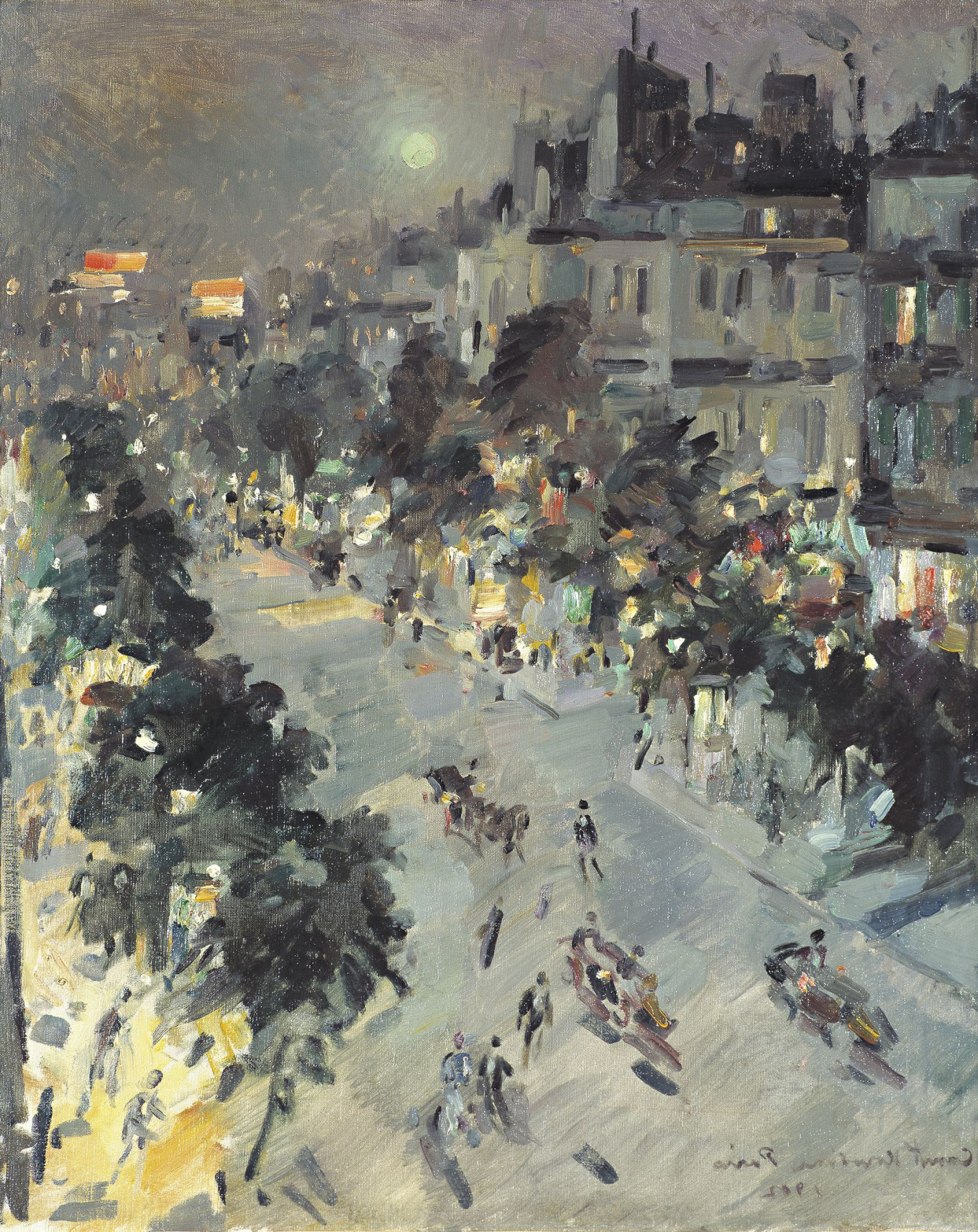

The exhibition also presents several works by the post-impressionists Paul Cezanne, Vincent van Gogh, and Paul Gaugin, included as contemporaries and younger peers of the impressionists. The show also includes Russian painters who “descended” from the peredvizhniki. “That's why we have Valentin Serov next to early Pablo Picasso and we show Nikolai Ge alongside with Paul Gaugin,” Antonova said. There are also works by Mikhail Vrubel and the “Russian impressionist” Konstantin Korovin.

This last section of the exhibition ushers in the 20th century. Russian art at the turn of the century made great strides that would lead to the avant-garde movement in the early 20th century. “That's when Malevich and Kandinsky appear on the scene and Russia becomes the most advanced country in terms of revolutionary art. This time other countries followed us,” Antonova said.

The show runs till February 25.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.