(Bloomberg View) — In many ways, Russia's current defiant geopolitical stance can be traced to a decisive moment in recent history: the belief that the West broke its promises not to expand the North Atlantic Treaty Organization eastwards. But experts argue over what exactly was promised, NATO itself calls the story of the broken promise a "myth," and the former Soviet president, Mikhail Gorbachev, who is critical of NATO expansion, has said the West kept all its binding commitments following from the reunification of Germany.

Now, George Washington University has taken a major step toward clarifying what exactly was promised and how, collecting a wealth of documents, all declassified in recent years, from the time Germany's reunification was negotiated. The many redactions — the U.S. has way too many secrets, as National Security Archive head Tom Blanton pointed out in a recent interview with my Bloomberg View colleague James Gibney — may hide important bits of the story.

But even with them, the collection shows that top officials from the U.S., Germany and the U.K. all offered assurances to Gorbachev and Foreign Minister Eduard Shevardnadze that NATO would not expand toward the Russian borders. The documents make clear that the Western politicians meant no expansion to Eastern European countries, not just the East German territory.

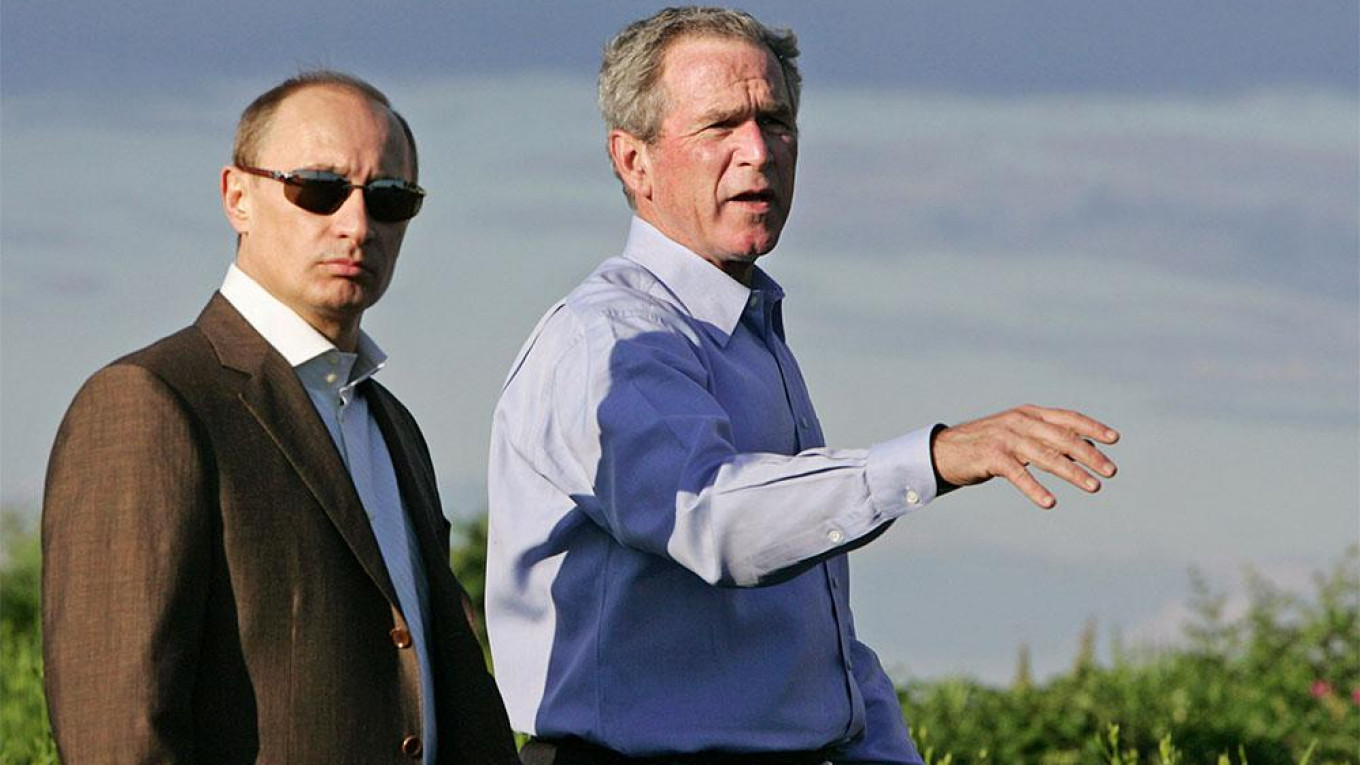

The assurances were never put on paper. But anyone looking for insights into President Vladimir Putin's worldview should take an interest in the GWU documents. They back up, to a certain extent, conclusions he appears to have reached on the basis of the Soviet records of these discussions.

It was West German Foreign Minister Hans-Dietrich Genscher who was charged with getting Soviet consent for his country's reunification. He understood a guarantee of NATO non-expansion was a key precondition of success, and said so both to the German public and to allies such as British Foreign Minister Douglas Hurd. The U.S., keen to keep unified Germany in NATO rather than grant it a neutral status, went along with Genscher's view. On Feb. 9, Secretary of State James Baker told Shevardnadze:

"A neutral Germany would undoubtedly acquire its own independent nuclear capability. However, a Germany that is firmly anchored in a changed NATO, by that I mean a NATO that is far less of a military organization, much more of a political one, would have no need for independent capability. There would, of course, have to be ironclad guarantees that NATO’s jurisdiction or forces would not move eastward. And this would have to be done in a manner that would satisfy Germany’s neighbors to the east."

On the same day, he repeated to Gorbachev, "If we maintain a presence in a Germany that is a part of NATO, there would be no extension of NATO’s jurisdiction for forces of NATO one inch to the east." That, he made clear, was the concession the Western bloc was offering in exchange for keeping Germany in NATO. Gorbachev replied that, in any case, "a broadening of the NATO zone is not acceptable." "We agree with that," Baker responded.

In simultaneous talks, Central Intelligence Agency Director Robert Gates put the same proposal to KGB chief Vladimir Kryuchkov.

As the discussions wore on, the Soviets pushed for a common security structure in Europe, based on the Organization for Security and Cooperation in Europe, formed almost two decades before as forum for cooperation between the Soviet and U.S.-led blocs. Western negotiators agreed but said they wanted to keep NATO, making it more benign and open to cooperation with the Soviets and their Warsaw Pact allies.

As late as March, 1991, six months after Germany became one country, British Prime Minister John Major was still assuring Soviet Defense Minister Dmitri Yazov -- who would soon take part in a conservative coup against Gorbachev that would end up destroying the Soviet Union -- that NATO was not going eastward, and that he "did not himself foresee circumstances now or in the future where East European countries would become members of NATO." For his part, then-NATO Secretary General Manfred Woerner assured a Russian delegation, which reported back to President Boris Yeltsin, that 13 out of 16 NATO members were against expansion as well as Woerner himself.

None of the reassuring talk turned into specific agreements because the Soviet Union was practically bankrupt, in need of the aid that Germany offered in exchange for acquiescence to its unification, and generally dependent on Western loans. It was in no state to demand anything from the West; even the insistence on a common security system was a bluff.

That's why Gorbachev, who doesn't like to admit he was desperate and unable to push back, has said that the West kept its promises -- or at least one promise: That no non-German NATO troops would be stationed in the former East Germany.

The U.S., unlike cautious Germany, was talking to the Soviets as a winner speaks to a loser, not particularly careful about non-binding offers and assurances to Gorbachev and Shevardnadze with . The Soviet leadership's power was eroding so fast that it was pointless to make carved-in-stone promises. So later, when the Soviet Union crumbled and East European countries wanted the Cold War victors' protection, there was also no point to keep them out of NATO.

That brings us back to Putin's style and worldview. He has clearly pored over Soviet documents from 1990 and 1991 -- he quoted Woerner on non-expansion in his famous, belligerent 2007 speech to the Munich Security Conference. And he appears to want to negotiate with the West the way he feels Westerners negotiated with the Soviets back then. That means, to him, feinting, dissembling, offering meaningless assurances of non-aggression, denying Russia's military actions in Ukraine, offering concessions in Syria that he never intended to make. Irritated Western interlocutors find that it's impossible to negotiate with him because he doesn't mean what he says and doesn't say what he wants. He sees it differently -- as talking like a winner.

Putin the ex-KGB officer appeared for a while to be a convert to Western ideas -- at least when he worked for St. Petersburg Mayor Anatoly Sobchak. But studying the Soviet collapse, which he has described as a tragedy, was almost certainly one of the factors that led him to revert to type. He became convinced the West will only respond to force. As he projects it, whatever he tells Western leaders is only cover -- just the game that, he appears to believe, Baker and President George H.W. Bush were playing with Shevardnadze and Gorbachev. Putin's worldview is one of all-embracing cynicism and mistrust. The broken promise story is his excuse -- not an entirely groundless one, judging by the GWU documents -- to refuse to play fair.

That's why the West is getting nowhere, and will get nowhere, with Putin. Moreover, it's highly unlikely that any successor to Putin will simply cast aside the broken promise story, which is by now embedded in the Russian government's post-Soviet DNA. For years, perhaps decades, maintaining a confrontation with Russia will be easier than rebuilding trust.

Leonid Bershidsky is a Bloomberg View columnist. He was the founding editor of the Russian business daily Vedomosti and founded the opinion website Slon.ru. The views and opinions expressed in opinion pieces do not necessarily reflect the position of The Moscow Times.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.