At the height of the Great Purges, the Soviet Union of Artists presented a collection of impressionistic paintings of women and children surrounded by pastel flowers and sunshine. The paintings by Mikhail Shemyakin ignored Stalin’s requirement that artists portray factory workers and farmers building a socialist utopia.

Shemyakin’s oeuvre, now being exhibited at the Museum of Russian Impressionism in the first retrospective in Moscow since 1976, demonstrates how one traditionalist bucked the demands of Soviet-era conformity by keeping a low profile and painting at home. “Mikhail Shemyakin; A Completely Different Artist” documents private life during the Stalinist 1930s through the exquisite oil paintings of an “impressionist-realist-cubist.”

Early Years

Shemyakin was used to being a black sheep. He was a grandson of Aleksey Abrikosov, an industrialist and banker whose legacy is the Abrikosov and Sons chocolate producers, now Babayevsky Conglomerate. Although Shemyakin’s family expected him to join the family business with his brothers, the young Mikhail didn’t thrive in academic studies. The family eventually transferred their unusual boy to Moscow Art School, where he studied with the great artists Valentin Serov and Konstantin Korovin.

Although Shemyakin had obvious talent, he built a name for himself slowly. His extended family grew accustomed to his profession, if never fully understanding the painter’s “new-fangled” style. Family legend has it that Shemyakin’s maternal grandmother Agrippina traveled to a gallery selling her grandson’s art in Nizhny Novgorod, but by the time she arrived, all the paintings had been purchased except one. The last painting was a landscape in an ethereal palette of white, light ochre and gray. Assuming that the light pigmentation meant the painting was only a sketch, the grand dame hustled out of the exhibition, refusing to buy a work that “hadn’t even been finished yet.”

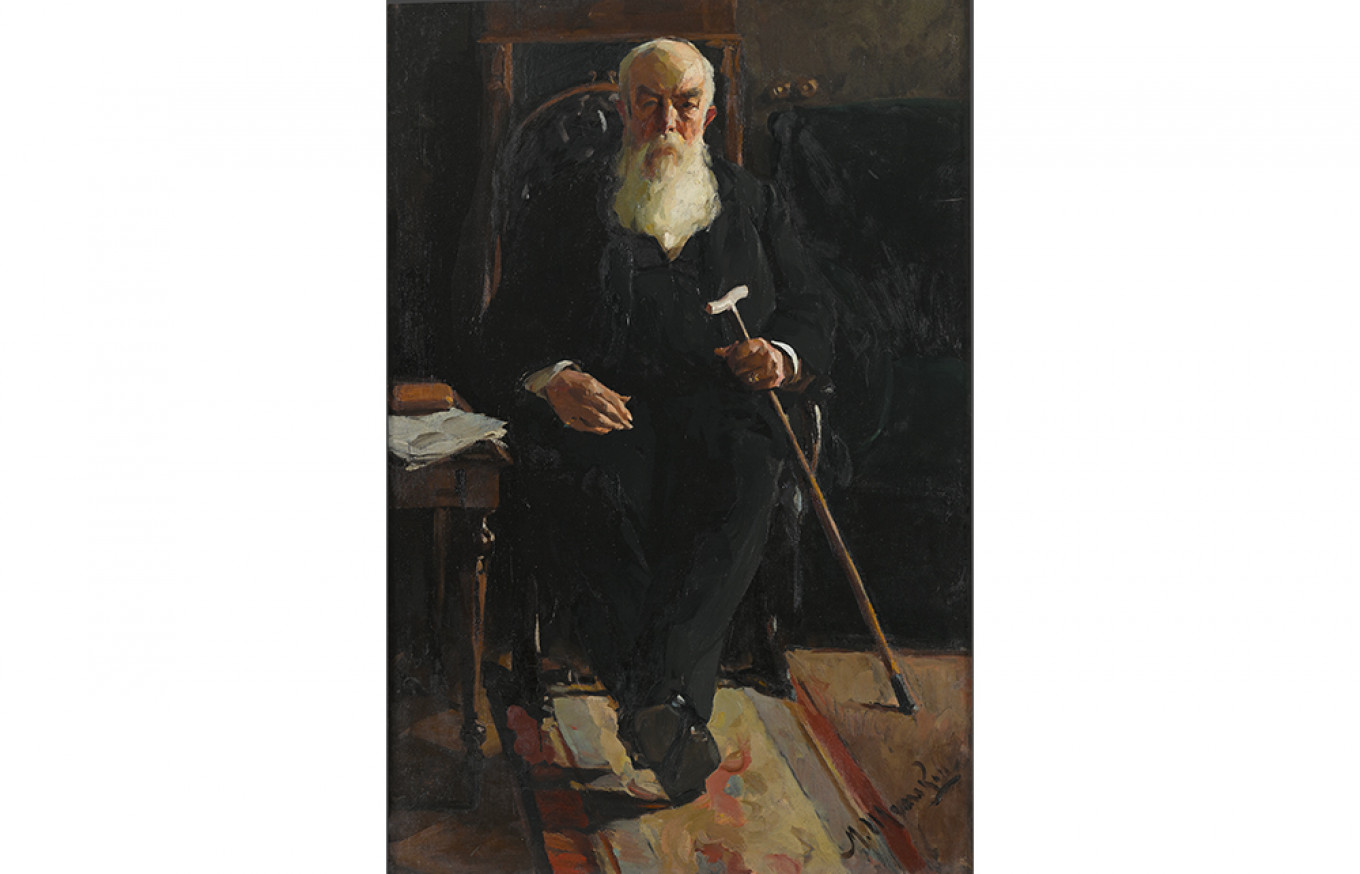

Shemyakin’s grandfather Abrikosov also had rather odd criteria for his grandson’s art. Commissioning a portrait from Shemyakin, the pater familius agreed to sit for 20 hours, “but not one minute longer,” Yulia Petrova, director of the Museum of Russian Impressionism, told The Moscow Times. When the painter showed his grandfather the finished portrait, the chocolate magnate went up to a mirror, carefully measured the length of his head from bald spot to beard, and then compared it to the size of his head in the painting. He approved, saying “Good work, Misha. Exactly right.”

Out of Step With the Revolution

Neither Shemyakin’s ethereal style nor his middle-class ancestry boded well for the artist after the 1917 Russian Revolution. But the Bolshevik emphasis on engineering, machinery, and construction inadvertently set Shemyakin on a successful career path. From 1918 until his death, the impressionist artist taught drawing at architecture and design colleges pioneering constructivist architecture, the Moscow Higher Engineering and Construction Institute, the Moscow Institute of Transport Engineers, the Military-Engineering Academy, and the Moscow Polygraphic Institute which taught print media.

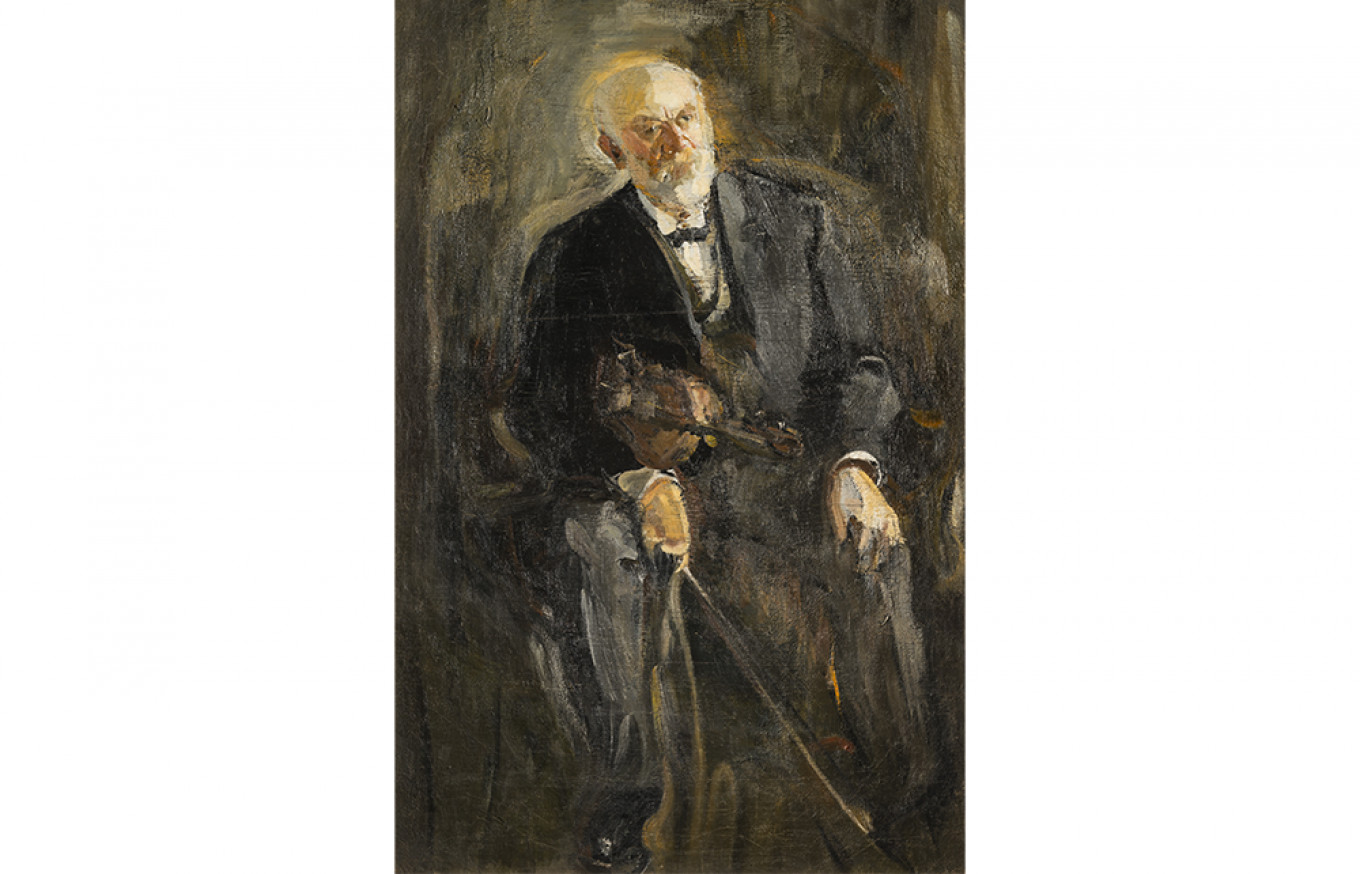

Between his multiple teaching responsibilities, Shemyakin lived a quiet life with his wife, two sons, and his wife’s parents. His father-in-law was Ivan Grzhimali (Jan Hřímalý), a Czech violin professor at the Moscow Conservatory. The family shared an apartment inside the conservatory building, and their spacious living room functioned as a salon, bringing together opera singers, string quartet ensembles, and of course, one painter.

Shemyakin’s father-in-law and their musical friends often sat for Shemyakin’s portraits.

“In my opinion, an artist is very fortunate to

paint people with whom he has a genuine interest,” said Petrova. “For an

artist, the opportunity to portray his dear ones is a happy occasion, and it

allowed [Shemyakin] to reveal more intimate themes in brighter colors,” than

with professional models.

Surviving Dark Days

By 1934 the state policy in the arts had changed from support and then tolerance for the avant-garde and artistic diversity to socialist realism. Artists were required to depict factory workers, machinery, and farm laborers not as they were but as they could be in a communist utopia.

As socialist realism became virtually the only acceptable form of art, it became clear that there would be consequences for those who did not conform to the doctrine. The composer Dmitri Shostakovich was publicly rebuked and his works were banned for many years. The theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold was arrested, tortured and executed in 1940. Hundreds of writers turned to translation and artists stopped showing their works. It’s astonishing that, in this fraught period for party functionaries and artists of all stripes, the Union of Artists exhibited Shemyakin’s decidedly non-Soviet paintings.

But Shemyakin operated on a lower level, as a teacher of future engineers; painting remained his private affair. He continued to portray his home life in pastels, emphasizing the play of light on the peaceful faces of his wife, sons, and sister-in-law. He painted hyacinths, the family’s favorite flower, as Stalin’s purges cut a swath through Moscow’s intelligentsia, and as conservatory professors and artistic colleagues disappeared in the dead of night.

In 1938, one of the most tragic years of the purges, the Union of Artists held a retrospective show of Shemyakin’s paintings as a sign of respect for the quiet man. The exhibit commemorated the 25th anniversary of his work as a teacher and 35th anniversary of his creative life.

Archivists at the Museum of Russian Impressionism located stenographer’s notes from a three-hour organization meeting before Shemyakin’s exhibit. The notes reveal that only one critic brought up Shemyakin’s lack of “Soviet themes,” according to Petrova.

Shemyakin continued to teach drawing through

WWII and he died peacefully of natural causes in 1944.

A Delight to the Eye

The Museum of Russian Impressionism has laid out Shemyakin’s work in two rooms that display the quiet dignity of the artist’s life. Most are portraits, but there are still lifes of flowers sprinkled throughout. His wife and young children bathe in a summery haze as they smile at the viewers and each other. In the portraits of musicians, brown-black brushstrokes radiate outwards from his subject’s clear gaze becoming rough and heavy at the periphery of the canvas. Shemyakin’s serious palette echoes the musicians’ formal dress and wooden instruments, a striking contrast to the hyacinth paintings which revel in their rainbows of white, blue and deep violet.

In general, the Shemyakin exhibit offers art

lovers respite from the ambitious intensity of better-known 20th century artists

displayed in Moscow’s world-class museums. Sheltered in the cozy Museum of

Russian Impressionism, itself tucked away in the former Bolshevik Chocolate

Factory, Shemyakin’s paintings tempt art lovers to “stop and smell the roses”,

or in this case, hyacinths.

Mikhail Shemyakin’s work can be seen at the Museum of Russian Impressionism through January 17.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.