In the fall of 1992, Russia was just starting on its path of economic transformation.

For 75 years, the Soviet Union had built an economic system based on state ownership of production, central planning and fixed prices. Changing the system through minor tweaking, as the Soviet leadership had wanted to do, was impossible. The system had to be destroyed.

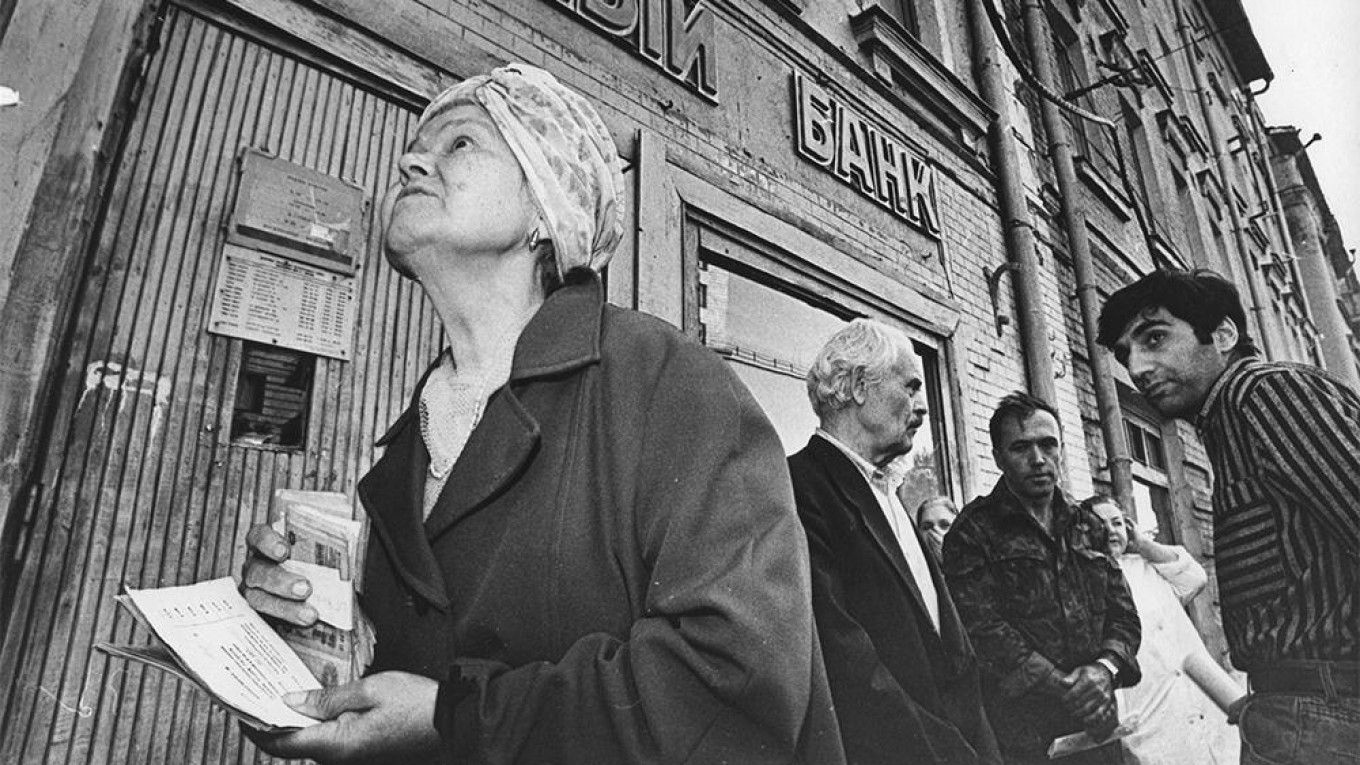

It seemed easy: “all” they had to do was release price controls and the ruble exchange rate. But the destruction was very painful. Hyperinflation took years to overcome — in fact, Russia got to “normal inflation” (under 5 percent) only in 2016.

At the end of the 1980s people thought that the main problem for the market economy would be the lack of specialists. But, although working in a market environment did require different skills and knowledge, as so often happens, you just roll your sleeves up and get down to work — despite your fear. Free market prices and privatization quickly put everything and everyone in their place.

On the other hand, a task that seemed easy turned out to be the most difficult and it is still not solved.

The Soviet economy was guided by the ideological dogma that it could produce everything it needed. In the early 1990s, it seemed that the Soviet economy had enormous intellectual and technological potential. The doors to international cooperation would open and Russia would become a full-fledged member of the global economy. But that didn’t happen.

At first the obstacle was the country’s macro-economic instability — few people wanted to invest in a country with an inflation rate topping 10 percent a month. Then, while Russia conducted long and substance-less negotiations over joining (or to be more precise, not joining) the World Trade Organization, Southeast Asia and then China became magnets for direct foreign investment.

Just when the Russian economy entered a phase of rapid growth, the Kremlin decided to strictly limit access to foreign capital. Russia voluntarily stepped off the road to globalization: the share of raw and simply processed materials topped 80 percent of all Russian exports.

Finally, the crisis of 2008 hit, bringing down with it the price of oil — and Russian prosperity. When the country recovered, it turned out that the economy didn’t have any drivers. Furthermore, the annexation of Crimea and presence of Russian troops in eastern Ukraine led to far-reaching economic sanctions against Russia. Oil prices fell even more. The Kremlin’s response to this was, softly put, strange: It isolated the economy even more.

In the modern world, economic self-isolation cannot lead to positive results.

Even if there are short-term gains, they cannot outweigh the long-term losses that inevitably occur. Today foreign investment is not so much an influx of financial resources as the spread of modern technology, access to modern equipment and — perhaps most important — access to human capital, to a highly qualified labor force that has managerial talent and skills. Economic globalization presupposes the free movement of labor and capital among countries. Not everyone likes globalization, but for developing countries it is essential for accelerated development and higher living standards.

As we look back at the last quarter of a century, we come to the sad realization that we weren’t able to transform the Soviet economy. It may be a market system, but Russia’s economy is no more integrated into the world economy than its Soviet predecessor.

Sergei Aleksashenko was Deputy Minister of Finance and Deputy Chairman of the Central Bank in the 1990s.

This article is part of The Moscow Times' 25th-anniversary special print edition. To view the entire issue click here.

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.