East of the Kremlin walls along the Moscow river embankment, rolling hills covered with birch groves and flora-rich meadows shield visitors from the city hubbub. The towering spires of St. Basil’s Cathedral and the Ivan the Great Bell Tower just peek over Zaryadye Park’s luscious horizon.

The city’s first new park in 50 years is designed according to the latest trends in landscape architecture. It has dazzled over 250,000 visitors since it opened to the public on Sept. 11, 2017.

But some Muscovites resent the project, and not just for its skyrocketing costs, which are projected to reach 25 billion rubles ($433.3 million) over the next two years.

Zaryadye Park sits atop the territory of Moscow’s oldest neighborhood outside the Kremlin. Preservationists and history lovers argue that the ultra-modern park has literally supplanted the city’s architectural heritage, destroying part of Moscow’s ancient heritage forever.

River Trade in Medieval Moscow

Developed during the 12th-13th centuries, Moscow’s traders organized the flow of goods from the banks of the Moscow River into the city. Zaryadye’s name means “the place behind the market rows” (za ryady) on Red Square. The neighborhood was surrounded by thick walls that made the second circle of defense outside the Kremlin. Zaryadye’s traders constructed stone churches, a monastery along Varvarka Street, and ornate wooden homes.

Regional traders moved their wares across the river and through the customs clearing houses (mytny dvor). Merchants from England displayed their wares in the English embassy (Angliisky Dvor), the 16th century equivalent of Moscow’s luxury mall GUM. The Romanov Family built a palace there. During the 15th and 16th centuries, well-paid court servants, prominent artisans, and merchant families wealthy from centuries of river trade occupied Zaryadye’s prime real estate.

Later, however, the neighborhood suffered a series of blights. After Peter I moved his court to St. Petersburg in 1713, Zaryadye was drained of its wealthiest inhabitants, who migrated to Russia’s new capital. To add insult to injury, Peter built a second defensive wall that prevented sewage from flowing into the river and out of the city. Zaryadye reeked. Unsanitary and unsafe, the proud neighborhood quickly became the least desirable district in Moscow.

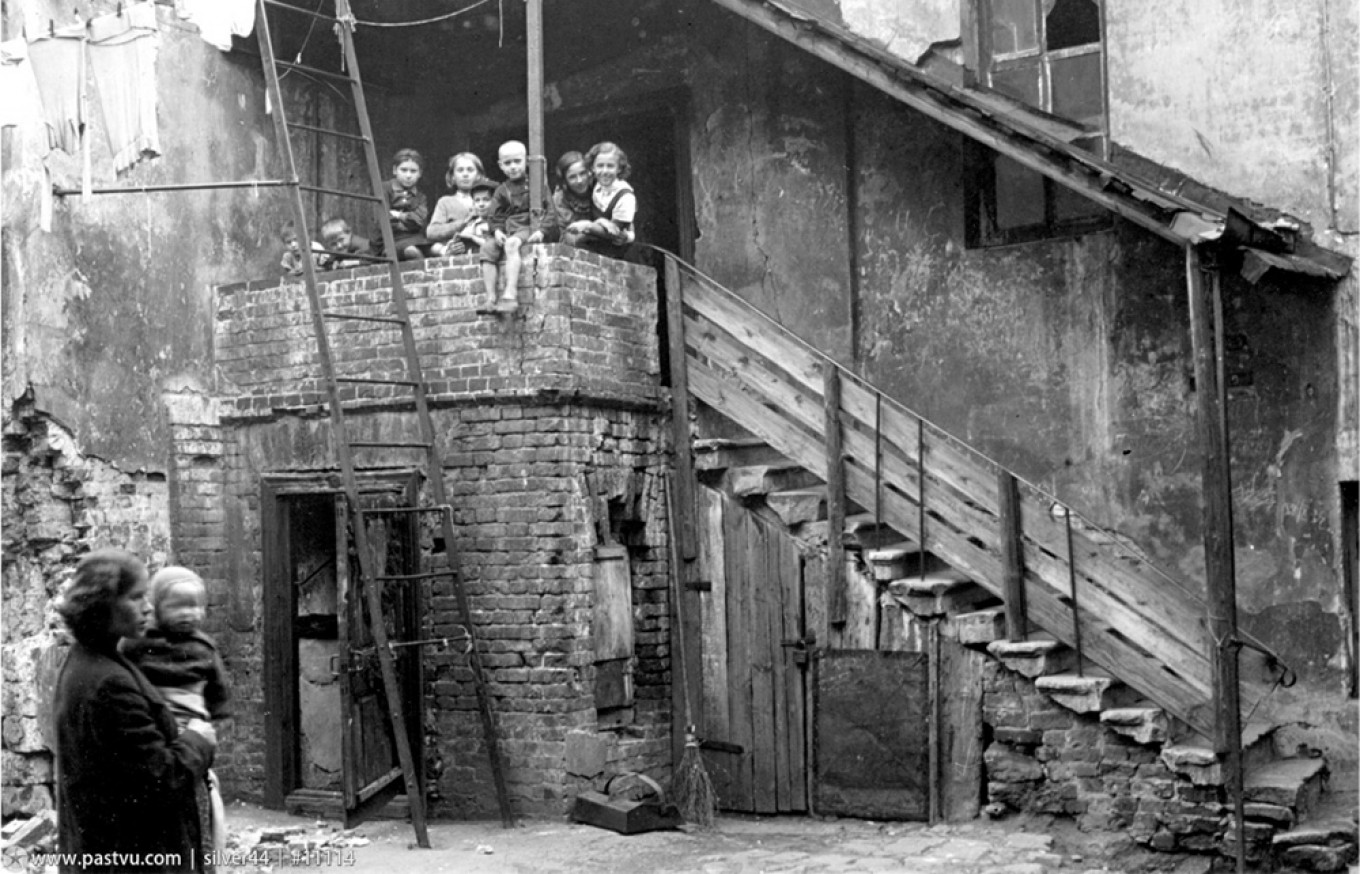

The great fire of 1812 destroyed most of Zaryadye’s homes but turned a new leaf in the neighborhood’s history. Moscow’s wealthy families constructed two to three story brick buildings on the cheap and rented them to factory workers in Russia’s nascent textile industry. Landlords scrimped on costs by building a single staircase for each building, linking the individual units by long “galleries,” balconies lining the inner courtyard on all floors. The new buildings stood so close to the ancient defensive wall that residents reached out their windows to plant flowers and greenery on top. If Zaryadye had survived the 20th century, its unique look would have placed it among Europe’s prized historic districts.

Moscow’s Jewish Ghetto

But Zaryadye’s reputation as an undesirable neighborhood remained. In the 19th century, it gained an ethnic character as the first landing spot for Jewish immigrants. Ambitious merchant families moved in, and former conscripted soldiers became small traders, tailors, and cobblers, or kosher grocers. Big Yiddish-speaking families crammed into Zaryadye’s two-story tenements. Over the next 30 years, tiny Zaryadye’s Jewish population grew to over 31,000, comparable to the famed ghettos of eastern Europe.

But anti-Semitism fueled pogroms in Ukraine and Polish territory and infiltrated the capital by the 1870s. The Governor-General of Moscow, Tsar Alexander II’s brother, evicted 20,000-30,000 Jews from the city in 1882, destroying Zaryadye’s economy. By the beginning of the 20th century, its stone buildings desperately needed repair.

Desecration of Heritage

Josef Stalin had great plans for Moscow’s urban development, none of which protected the city’s architectural heritage. In 1935, the state outlined its master plan: whole city blocks would be “ensembles” with matching facades, each block would increase in length, and buildings would be seven to fourteen stories tall.

Zaryadye’s 120-year-old, two-story slums had no place in Stalinist Moscow. In 1936, Soviet developers demolished the section of Zaryadye by the Kremlin walls to make space for the entrance ramps to the Bolshoi Moskovoretsky Bridge. In 1947 most of the neighborhood was torn down for a planned eighth skyscraper to match Moscow’s other “Seven Sisters.” The third round of destruction in the early 1960s made way for the Hotel Rossiya.

Finished in 1969, the Hotel Rossiya dwarfed St. Basil’s Cathedral. Architect Dmitry Chechulin matched contemporary iron and glass architecture with the grandiosity of the Stalinist high-rises. The 21-story hotel’s massive block could accommodate over 5,000 guests. It contained a post office, health club, nightclub, a movie theater, hair salon, and a police station with jail cells. Its State Central Concert Hall seated 2,500.

The project destroyed all but seven of the oldest buildings in Zaryadye that lined the south side of Ulitsa Varvarka and a small part of the wall. The 16th century St. Anna’s Church at the corner remained at the hotel’s southwestern edge.

Make Way for the New. Again.

But the Hotel Rossiya did not remain modern forever—in the 1990s it began to take on losses, and in 2006, the city authorities demolished it.

The gaping hole in Zaryadye offered Moscow’s mayors the opportunity to leave a permanent mark. Mayor Yuri Luzhkov promised to design an extensive entertainment area, but the project fell through after his replacement, Sergei Sobyanin, came to power in 2010.

Armed with a vision of a “more flexible, modern capital,” Mayor Sobyanin and his Chief Architect Sergei Kuznetsov have been busy giving the city center a face-lift. Driven by 21st-century principles of urban design, Sobyanin and Kuznetsov have spent the last five years laying wide sidewalks of paving stone, opening the Moscow River embankment up for bike paths, and developing a plan to tear down the city’s Khrushchev-era apartment buildings. Although the idea to create a park on the territory is attributed to President Vladimir Putin, the ultra-modern Zaryadye Park is Sobyanin’s pet project.

When Sobyanin initially collected proposals for Zaryadye Park, Moscow preservationists welcomed the idea. Arkhnadzor, a historical preservation society, lobbied heavily for large-scale archaeological excavations of Zaryadye during the early stages of construction.

“We hoped that they would find something interesting,” Alexander Frolov, an Arkhnadzor member, told The Moscow Times. “It would have been possible to organize an excavation of it, to study a wider area, and to show more of the historic importance and exhibit a larger quantity of objects.”

In 2012, Sobyanin and his crew commissioned a conceptual landscape design from the group who built New York City’s High Line park. The winning project all but ignores the neighborhood’s history. Although Diller Scofidio + Renfro left the district’s 500-year-old buildings on Ulitsa Varvarka untouched.

A Park for the New Millennium

Built from 2013-2017, Zaryadye Park has three layers. At its foundation lies an underground parking garage with space for over 400 cars; from there visitors can access an underground media center and the Philharmonia concert hall, whose glass roofs break above ground surrounded by greenery, rolling hills, and two ponds.

The concept park pays tribute, at least in name, to Russian nature, consisting of four climatic zones: a birch and pine forest, tundra, steppe, and floral meadows. Plants from the warmer Caucasus region are housed under the glass dome, to be heated by solar panels in the winter.

Ironically, the architects spent 470.5 million rubles (over $8 million) on imported plants from Germany, according to the Vedomosti newspaper’s review of Zaryadye contractor’s bill.

Zaryadye Park’s paved walkways merge into plant-covered areas without borders, encouraging visitors into the green spaces for a picnic on the grass, an about-face from the Soviet-era “look but do not touch” approach to city parks. Its innovative lack of boundaries may have encouraged the first crowds of visitors to damage the park, breaking glass solar panels in the dome, scratching lampposts, trampling freshly-planted grass, and even digging lichens and moss out of the garden as souvenirs.

The designers made sure to top some records— the Concert Hall’s roof is covered by the world’s biggest translucent structure without partition walls. The world’s longest “floating bridge” extends over the Moscow River, offering visitors a new viewing platform overlooking the Kremlin.

But Zaryadye’s history is almost completely obliterated. In its place is the city’s new jewel, billed as “a grand recreational zone in the heart of the capital, an innovative site of the 21st century.”

***Zaryadye Park is open on Monday from 2 p.m. until 10 p.m. and on Tuesday through Sunday from 10 a.m. until 10 p.m. Entrance is free.***

A Message from The Moscow Times:

Dear readers,

We are facing unprecedented challenges. Russia's Prosecutor General's Office has designated The Moscow Times as an "undesirable" organization, criminalizing our work and putting our staff at risk of prosecution. This follows our earlier unjust labeling as a "foreign agent."

These actions are direct attempts to silence independent journalism in Russia. The authorities claim our work "discredits the decisions of the Russian leadership." We see things differently: we strive to provide accurate, unbiased reporting on Russia.

We, the journalists of The Moscow Times, refuse to be silenced. But to continue our work, we need your help.

Your support, no matter how small, makes a world of difference. If you can, please support us monthly starting from just $2. It's quick to set up, and every contribution makes a significant impact.

By supporting The Moscow Times, you're defending open, independent journalism in the face of repression. Thank you for standing with us.

Remind me later.